Executive Summary

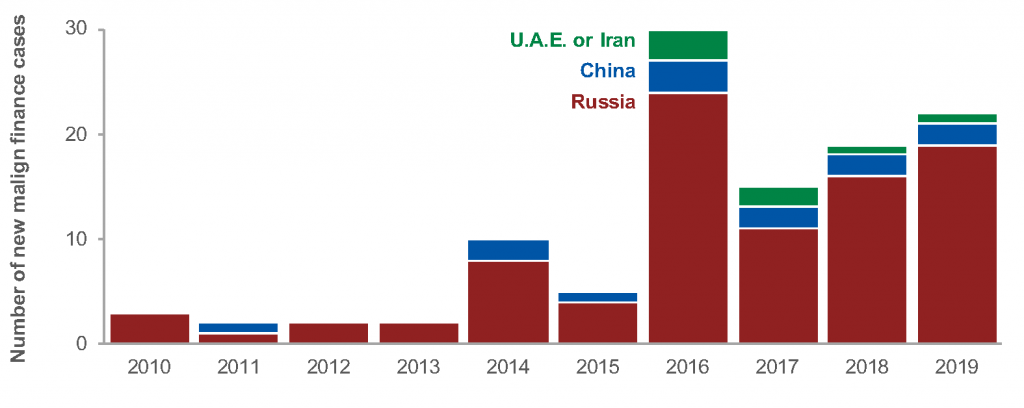

In addition to more widely studied tools like cyberattacks and disinformation, authoritarian regimes such as Russia and China have spent more than $300 million interfering in democratic processes more than 100 times spanning 33 countries over the past decade. The frequency of these financial attacks has accelerated aggressively from two or three annually before 2014 to 15 to 30 in each year since 2016.

We call this tool of foreign interference “malign finance,” defined as “the funding of foreign political parties, candidates, campaigns, well-connected elites, or politically influential groups, often through non-transparent structures designed to obfuscate ties to a nation state or its proxies.” A typical case involves a regime-connected operative funneling $1 million to a favored political party, although buying influence in a major national election costs more like $3 million to $15 million.

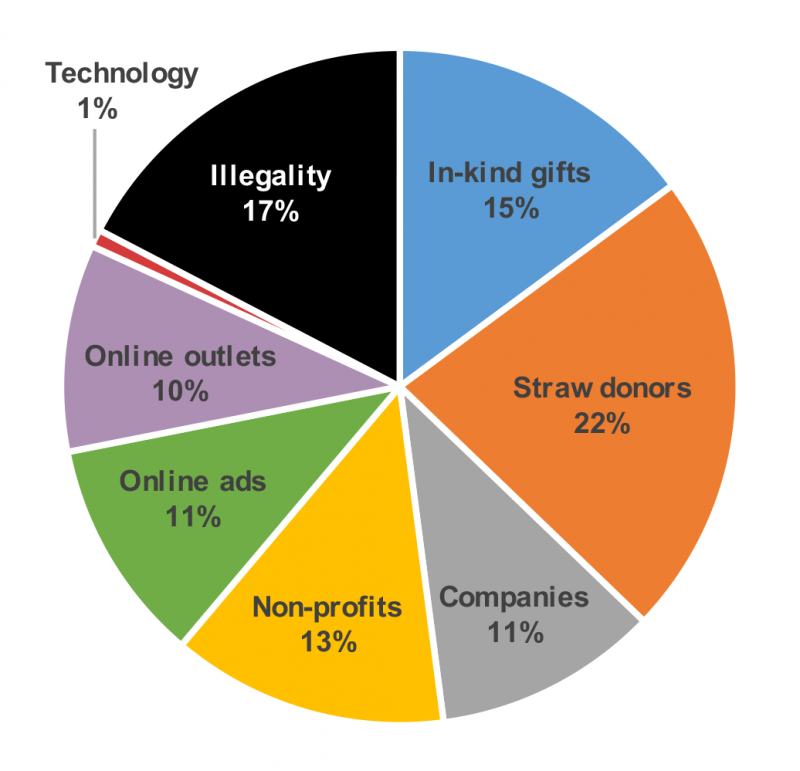

Rather than start our analysis by focusing on any given policy area, we review open-source reporting in 16 languages to identify malign finance cases credibly attributed to foreign governments. Finding that approximately 83 percent of the activity was enabled by legal loopholes, we catalogue the resulting caseload into the seven most exploited policy gaps.

Breakdown of loopholes through which authoritarian regimes secretly funnel money into democratic politics

Broader than just money flowing through straw donors, shell companies, non-profits, and other conduits, malign finance includes a range of support mechanisms innovated by authoritarian regimes to interfere in democracies, from intangible gifts to media assistance. As such, policy strategies to address these vulnerabilities are not limited to campaign finance reforms, but also include greater transparency requirements around media funding, corporate ownership, campaign contacts with foreign powers, and other issues.

In addition to identifying loopholes, our case study informs the scope of our recommended policy solutions, which are meant close off channels for foreign financial interference without infringing upon the speech rights of domestic political spenders or jeopardizing bipartisan support. Each of our recommendations balances these trade-offs differently based on empirical, legal, political, and administrative considerations vetted in consultation with more than 90 current and former executive branch officials, Congressional staffers from both parties, constitutional law scholars, and civil society experts.

This report is organized around each of the seven U.S. legal loopholes that need to be closed, starting with the most urgent priorities, plus an eighth chapter on the need for stronger governmental coordination.

-

Broaden the definition of in-kind contributions

Legal definitions of political donations are too narrowly scoped in many countries, effectively legalizing some foreign in-kind contributions. Examples include loans to Marine Le Pen’s party from banks controlled by Russian leader Vladimir Putin and his proxies, luxurious gifts and trips paid for by Russian oligarchs in Europe and Chinese United Front operatives in Australia, and black-market services provided by Kremlin instrumentalities.1 U.S. President Donald Trump invited foreign support in two consecutive presidential elections, enabled by a narrow reading of the U.S. prohibition against foreign nationals contributing anything of value.2

The term “thing of value” should be more broadly defined, interpreted, and enforced, such that it unambiguously includes intangible, difficult-to-value, uncertain, or perceived benefits. The most robust form this change could take would be new legislation, although a similar result could be achieved by the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Federal Election Commission (FEC) enforcing existing law more broadly.

-

Report campaign contacts with agents of foreign powers

Authoritarian regimes send intermediaries on secret missions to enrich favored donors, politicians, or parties, as demonstrated by operations on four different continents. Nine elite Russian expatriates who donated to the U.K. Tories are named in the classified annex of a parliamentary report on Russian threats to British democracy.3 Zhang Yikun, a leader in China’s United Front work, is implicated in multiple cases of funneling money to New Zealand political parties and candidates.4 Yevgeny Prigozhin, Putin’s go-to oligarch for deniable hybrid warfare operations, offers package deals—including backpacks of cash, tailor-made news outlets, troll farms, and armed forces—to help the Kremlin’s preferred African leaders and presidential candidates obtain and hold on to power.5 The U.S. Department of Justice indicted George Nader, an American advisor to the ruler of the United Arab Emirates, for allegedly funneling more than $3.5 million to the 2016 campaign of Hillary Clinton in order to gain access to and influence with the candidate and then use that to gain favor with, and potential financial support from, the U.A.E.6

U.S. campaigns should have to report to law enforcement offers of assistance from foreign powers. Legislation like the SHIELD Act would require that type of reporting, although Congress should consider removing the exemption for contacts with foreign election observers, clarifying a broad definition of agents, covering big donors, and more narrowly scoping it toward non-allied countries to avoid closing off space for benign foreign relations.7

-

Outlaw anonymous shell companies and restrict subsidiaries of foreign parent companies

Foreign governments and their operatives use corporate entities, similar to their usage of human straw donors, as footholds to establish a legal presence—and thus the ability to donate—within target countries. This problem is most pervasive in the Anglo-American financial system, which offers deep asset markets, secure property rights, and the ability to incorporate without identifying owners. For example, Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman used an anonymous Delaware shell company to hide contributions funded by elite Russian businessmen, while a web of London-based entities tied to Kremlin-connected oligarch Dmytro Firtash have donated to numerous British politicians.8

Legislation like the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 would outlaw anonymous shell companies by forcing U.S. firms to report their true (beneficial) owners to the Treasury Department.9 This information would be held securely and confidentially, disclosed only to support law enforcement investigations. While shell companies are by far the most important corporate vulnerability, Congress should also take targeted steps to tighten restrictions on political activity by U.S. subsidiaries of foreign parent companies, such as making CEOs certify compliance or blocking donations by firms substantially owned by nationals of adversarial countries. However, this subsidiary loophole has mostly been exploited for corrupt commercial motives rather than geopolitical operations meant to weaken target societies.

-

Disclose foreign donors to non-profits

Foundations, associations, charities, religious organizations, and other non-profits are handy vehicles for malign finance because Western legal systems treat them as third parties permitted to spend on politics without meaningfully disclosing the identities of their donors. For example, far-right parties in Europe such as Alternative for Germany, the Freedom Party in Austria, and the League in Italy each have non-profit conduits that can channel foreign money into elections.10 Russia secretly funds non-profits serving as bespoke fronts to execute specific mandates, like a Dutch think tank campaigning against a Ukrainian trade deal with the European Union, a Delaware “adoptions” foundation lobbying against sanctions on Russia, environmental groups opposing U.S. hydraulic fracking, and a Ghanaian nonprofit employing trolls pretending to be African Americans.11 Lastly, non-profits have been used as vehicles for elite capture, such as bribery run through CEFC China Energy, Firtash’s use of his British Ukrainian Society to influence elites in London, and Russian secret agents and money launderers working to cultivate top U.S. politicians through the National Rifle Association.12

Legislation like the DISCLOSE Act would require U.S. non-profits that advocate for a clearly identified political candidate to publicly disclose the identities of their donors, whether they are foreign or domestic.13 We also propose legislation more targeted toward malign finance, avoiding public disclosure requirements for domestic “dark money” groups. It would require all U.S. non-profits—whether they spend on politics or not—to report the identities of all their funders to law enforcement, while only having to publicly reveal their foreign funders. Compared to the DISCLOSE Act, this proposal would include 501(c)(3) charitable organizations, exclude corporations, identify beneficial owners, include forms of income beyond just donations, and require reporting of financial audits.

-

Disclose online political ad buyers and ban foreign purchases

Russia, China, Iran, and other foreign powers continue to buy political ads on social media platforms in order to covertly influence elections and public opinion in democratic societies.14 These secret ad campaigns are often legal because online ads are not subject to the same disclosure rules and foreign restrictions applicable to print and broadcast media.

A bill like the Honest Ads Act would require public disclosure of the sources of payment for online political ads, similar to rules that have long applied to traditional ad mediums.15 Legislation like the PAID AD Act would expand the foreign source ban to apply to ad purchases at any time, not just the period when U.S. buyers are regulated a month or two before elections.16 It would further prohibit foreign governments from buying issue ads in election years to influence the election. Those types of rules around ad purchases should extend to beneficial owners, while prohibitions like the PAID AD Act could be limited to adversarial countries.

-

Disclose foreign funding of media outlets

The cutting edge of Russian interference appears to be the intersection of malign finance and information manipulation, including covert funding of online media outlets. European intelligence services see the Kremlin’s hand behind financial and content support for at least six far-right news websites in Sweden, thousands of short-lived “junk websites” in Ukraine, and purportedly independent local news outlets based in Berlin and the Baltics.17 Investigative journalists have scrutinized U.S.-based fringe internet news sites suspected of receiving foreign funding, but have not found definitive answers because their finances are well-kept secrets and no disclosure is required.18

U.S. technology companies should have to maintain publicly accessible “outlet libraries,” similar to the “ad libraries” required by Honest Ads except that they would mandate disclosure of the beneficial owners who fund online media outlets using internet services provided by U.S. technology companies. Similar to how U.S. banks are employed to enforce sanctions and are responsible for collecting and verifying beneficial ownership information, the legal obligation to operate these proposed outlet libraries should fall to U.S. web hosting providers, domain registrars, search engines, advertising technology firms, and social network platforms. Online media outlets wanting to use these services would need to provide tech companies with the identities of their funders—including equity owners, advertisers, and donors—for inclusion in the library. Covered outlets should include news organizations whose websites receive more than 100,000 unique monthly visitors or social media engagements while excluding publicly traded companies and other outlets already required to disclose ownership. The scope could be further limited to outlets receiving at least 10 percent of their financial support from abroad and require disclosure only of those foreign funders.

For traditional media outlets, Congress should require the FCC to again prohibit foreign-owned companies from acquiring more than 25 percent of U.S. broadcast licenses or at least give Congress a chance to overrule allowances. Lawmakers should require public disclosure when foreign agents like Sputnik and RT seek time on U.S. airwaves and clarify on-air disclaimers so that listeners know when they are hearing propaganda sponsored by the Russian government rather than just receiving an hourly attribution to some parent corporation that most Americans have never heard of.

-

Ban crypto-donations and report small donor identities to the FEC

In order to conceal financial flows into Western politics, authoritarian regimes have shown an intent to exploit two emerging technologies offering anonymity. First is the threat of political spending in the form of cryptocurrencies, a medium of exchange that Russian military intelligence mined, acquired, laundered, and spent on its 2016 hack-and-dump infrastructure because it is easier to keep off the radar of U.S. authorities.19 Second is the risk of donor bots capable of automating thousands of political contributions in the names of stolen identities, keeping such operations under wraps by capping donations at the $200 disclosure threshold.20

Donations and political ad purchases in the form of cryptocurrencies should be completely prohibited. Small donor disclosures require more nuanced handling. Campaigns, parties, and super PACs should have to report small donor identities to the FEC, which should make the information publicly accessible through a secure, limited, and conditional gating process. Any member of the public requesting access to the data should have to complete a security check and commit to not publicly disseminate or misuse personal information. This would deter stalkers, snoops, and other bad actors from abusing the data while enabling investigative journalists, watchdogs, and academics to analyze it for patterns of possible straw donor schemes.

-

Coordinate across the executive branch and reform the FEC and Treasury

A particularly aggressive 17 percent of malign finance cases do not operate primarily through legal loopholes. Examples include Russian oil profits earmarked to fund the League in Italy and various United Front bribery and straw donor schemes.21 When authoritarian regimes are caught breaking the law in ways that involve large sums of money, that boldness is often reflective of broader multi-vector influence campaigns authorized at the highest levels.

U.S. administrative responses to foreign interference campaigns need to be similarly supported by the president and coordinated “in a sweeping and systematic fashion.”22 The Alliance for Securing Democracy has recommended appointing a foreign interference coordinator at the National Security Council, creating a Hybrid Threat Center at the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, and establishing other avenues for coordination.23 We explain how economic departments and agencies should feed into these coordinating bodies, how the FEC needs structural reform to overcome partisan gridlock, and how Treasury should reorganize to dedicate as much administrative priority to fighting authoritarian influence as it does to combatting terrorist financing.

Global surge of malign finance

Most cases of malign finance we identify over the past 10 years occurred in the second half of the decade: 78 percent since 2016 and 92 percent since 2014. We are confident this marks a true acceleration—rather than the West simply paying more attention—because of detailed reporting on regional strategic influence campaigns approved by heads of state. Putin authorized campaigns against Europe in 2014, the United States in 2016, and Africa in 2018.24 Chinese leader Xi Jinping elevated United Front work in 2014 and 2015, which has primarily targeted the Asia-Pacific but also extended to support the Belt and Road Initiative as far west as the Czech Republic and Africa.25

The largest regional concentration of malign finance involves Russia targeting Europe, which represents about half of the activity in our study. That is why U.S. intelligence and law enforcement officials have traditionally seen foreign political funding as a more pressing challenge for Europe than the United States.26 That sense of safety is now gone, however, with U.S. officials warning in early 2020 that Russian interference in the U.S. election could not only reprise the 2016 tactics of disinformation and cyberattacks but also introduce covert financial support to political candidates or campaigns.27 Indeed, our case study reveals that the most common target of malign finance—hit more than 25 times—is the United States.

Groundwork for sweeping policy overhaul

The last time the United States faced an emerging threat of civil infrastructure converted into asymmetric weaponry, the adversary’s arsenal did not include dirt on opponents, straw donors, shell companies, non-profits, ads, media outlets, or emerging technologies. Rather, it was airplanes flying into buildings.

Over the seven weeks following 9/11, among other responses, the U.S. government enacted the most sweeping overhaul in a generation to its anti-money laundering laws, started reorganizing executive branch agencies and functions around combatting terrorist financing, and persuaded 30 countries to impose similar financial security protections.28 One reason why U.S. policymakers were ready to hit the ground running was that Congress—having seen the Russia mafia laundering billions through New York—spent the previous two years investigating how foreign financial institutions exploit loopholes in the U.S. financial security architecture in order to formulate bipartisan policy solutions.29

The United States has failed to similarly fortify its financial defenses since malign finance and other tools of election interference became top national security threats in 2016, although some preliminary policy development work has begun. About half of the reforms we recommend mirror or build upon legislation already introduced in Congress, like the SHIELD Act, AML Act, DISCLOSE Act, Honest Ads Act, PAID AD Act, and FEC structural reforms in H.R. 1, even if in some cases we propose modifications to bills like these to ensure their scope targets the malign activity observed in our survey.30 The other half of our recommendations are split among executive branch coordination, some straightforward statutory amendments, and five newly developed proposals: broadening the definition of a “thing of value,” requiring all non-profits to publicly disclose foreign funders, creating “outlet libraries” to identify beneficial owners, improving rules for traditional media, and mandating small donor reporting. These proposals would require some public debate and drafting work that should begin now in order to be ready when a political window opens. At the same time as we work to put our own financial security house in order, the United States should lead the democracies of the world to promote an open, transparent, and secure arena for political finance.

Our hope is that the comprehensive empirical research provided in this report on financial loopholes exploited by authoritarian regimes to fund political interference in democracies will jumpstart a policy reform initiative to build resilience against this threat. There is no time to lose. Just like airplanes in the summer of 2001 and cyberattacks in the summer of 2016, the system is currently blinking red about incoming rubles and yuan.

Please click the link to the right to read the rest of the report.

- See The Alliance for Securing Democracy and C4ADS, Illicit Influence—Part One—A Case Study of the First Czech Russian Bank, Washington, December 28, 2018; Antton Rouget et al., “La vraie histoire du financement russe de Le Pen,” Mediapart, May 2, 2017; Fabrice Arfi, et al., “La Russie au secours du FN : deux millions d’euros aussi pour Jean-Marie Le Pen,” Mediapart, November 29, 2014; Anton Shekhovtsov, Russia and the Western Far Right, 1st ed., London: Routledge, 2017, pp. 196-197; Anna Henderson and Stephanie Anderson, “Sam Dastyari’s Chinese donations: What are the accusations and is the criticism warranted?” ABC, September 5, 2016; Damien Cave, “Australia Cancels Residency for Wealthy Chinese Donor Linked to Communist Party,” The New York Times, February 5, 2019; Sam Jones, “Russia case causes headache for Swiss law enforcement,” Financial Times, June 5, 2020; Samer al-Atrush, “How a Russian Plan to Restore Qaddafi’s Regime Backfired,” Bloomberg, March 20. 2020; Roman Badanin, et al., “Coca & Co.: How Russia secretly helps Evo Morales to win the fourth election,” Proekt, October 23, 2019; Gabriel Gatehouse, “German far-right MP ‘could be absolutely controlled by Russia’,” BBC, April 5, 2019; Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller, Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election, U.S. Department of Justice, March 2019, Vol. I, pp. 44-57 (“Mueller Report”). The United Front is the arm of the Chinese Communist Party that co-opts and neutralizes sources of potential opposition through subversion of Chinese organizations and personages around the world. See Alexander Bowe, China’s Overseas United Front Work: Background and Implications for the United States, Washington: U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, August 24, 2018, pp. 3-4.

- See Mueller Report, Vol. I, pp. 49, 185-188, 188-191; United States House of Representatives, Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, The Trump–Ukraine Impeachment Inquiry Report, Washington, December 2019, pp. 98-103 (“Trump–Ukraine Report”); Devlin Barrett, et al., “Trump offered Ukrainian president Justice Dept. help in an investigation of Biden, memo shows,” Washington Post, September 26, 2019; Josh Dawsey, “Trump asked China’s Xi to help him win reelection, according to Bolton book,” Washington Post, June 17, 2020.

- Tom Harper and Caroline Wheeler, “Russian Tory donors named in secret report,” The Times, November 10, 2019.

- Sam Hurley, “National Party donations case: SFO alleges ‘trick or stratagem’ over two $100k contributions,” NZ Herald, February 18, 2020; John Anthony et al., “Chinese businessman Yikun Zhang’s donations go beyond Simon Bridges,” Stuff, October 17, 2018; Anne-Marie Brady, “Magic Weapons: China’s political influence activities under Xi Jinping,” 2017, Paper presented at The corrosion of democracy under China’s global influence, Arlington, VA, September 16-17, 2017, Washington: Wilson Center, 2017.

- See Neil MacFarquhar, “Yevgeny Prigozhin, Russian Oligarch Indicted by U.S., Is Known as ‘Putin’s Cook’,” The New York Times, February 16, 2018; Ilya Rozhdestvensky, et al., “Master and Chef: How Russia interfered in elections in twenty countries,” Proekt, April 11, 2019; Ilya Rozhdestvensky and Roman Badanin, “Master and Chef: How Evgeny Prigozhin led the Russian offensive in Africa,” Proekt, March 14, 2019.

- Indictment, United States v. Andy Khawaja, George Nader, et al., No. 1:19-cr-00374 (D.D.C., November 7, 2019), Doc. 1, pp. 6, (“Khawaja–Nader Indictment”); David D. Kirkpatrick and Kenneth P. Vogel, “Indictment Details How Emirates Sought Influence in 2016 Campaign,” The New York Times, December 5, 2019. Nader and his straw donors conspired to cause four political committees supporting Clinton “to unwittingly file false campaign finance reports concealing these unlawful campaign contributions from the FEC and the public by falsely stating that the contributions were made by [the straw donors] when in reality they were funded by Nader.”

- United States Congress, H.R.4617 – SHIELD Act, introduced October 8, 2019.

- See Indictment, United States v. Lev Parnas, Igor Fruman, et al., No. 1:19-cr-725 (S.D.N.Y. October 9, 2019), Doc. 1, pp. 5-10 (“Parnas–Fruman Indictment”); Greg Farrell, et al., “Rudy Giuliani Sidekick Lev Parnas Traces Part of Money Trail to Ukraine,” Bloomberg, January 23, 2020; Benoît Faucon and James Marson, “Ukrainian Billionaire, Wanted by U.S., Builds Ties in Britain,” The Wall Street Journal, December 2, 2014.

- United States Congress, S.Amdt.2198 to S.4049 – AML Act, submitted June 25, 2020. An earlier version of this legislation was called the ILLICIT CASH Act.

- See Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Germany, Parliamentary Elections, 24 September 2017: Final Report, November 27, 2017, pp. 6; Lobby Control, Geheime Millionen und der Verdacht illegaler Parteispenden: 10 Fakten zur intransparenten Wahlkampfhilfe für die AfD, Cologne, September 2017; Süddeutsche Zeitung, “Strache-Video,” 2019-2020; Oliver Das Gupta, et al., “Was außer Spesen noch gewesen ist,” Süddeutsche Zeitung, May 16, 2020; Thomas Morley and Etienne Soula, “Caught Red Handed: Russian Financing Scheme in Italy Highlights Europe’s Vulnerabilities,” The Alliance for Securing Democracy, July 12, 2019.

- See Zembla and De Nieuws BV, “Baudet and the Kremlin,” YouTube video, 48:41, April 25, 2020; Clarissa Ward, et al., “Russian election meddling is back — via Ghana and Nigeria — and in your feeds,” CNN, April 11, 2020; Emma Loop, et al., “A Lobbyist At The Trump Tower Meeting Received Half A Million Dollars In Suspicious Payments,” Buzzfeed, February 4, 2019; James Freeman, “What Did Hillary Know about Russian Interference?” The Wall Street Journal, July 10, 2017.

- See United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, “Patrick Ho, Former Head Of Organization Backed By Chinese Energy Conglomerate, Sentenced To 3 Years In Prison For International Bribery And Money Laundering Offenses,” Press Release, March 25, 2019; Sergii Leshchenko, The Firtash octopus: Agents of influence in the West, Vienna: Eurozine, September 25, 2015; Statement of Offense, Plea Agreement, United States v. Mariia Butina, No. 1:18-cr-218 (D.D.C. December 13, 2018), Doc. 67, pp. 1-5 (“Butina Plea Agreement”).

- United States Congress, S.1147 – DISCLOSE Act, introduced April 11, 2019. The DISCLOSE Act would apply to corporations, LLCs, labor unions, 527 organizations, and tax-exempt entities organized under section 501(c) of the tax code, except for 501(c)(3) charities because they are prohibited from spending on elections.

- See, e.g., Ward, 2020; Facebook, “Taking Down More Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior,” August 21, 2018; David Gilbert, “China’s Been Flooding Facebook With Shady Ads Blaming Trump for the Coronavirus Crisis,” Vice, April 6, 2020.

- United States Congress, S.1356 – Honest Ads Act, introduced May 7, 2019.

- United States Congress, H.R.2135 – PAID AD Act, introduced April 8, 2019.

- See Jo Becker, “The Global Machine Behind the Rise of Far-Right Nationalism,” The New York Times, August 10, 2019; Anatoliy Bondarenko, et al., “We’ve got bad news,” Texty, November 28, 2018; Bradley Hanlon and Thomas Morley, “Russia’s Network of Millennial Media,” The Alliance for Securing Democracy, February 15, 2019; Holger Roonemaa and Inga Spriņģe, “This Is How Russian Propaganda Actually Works In The 21st Century,” Buzzfeed, August 29, 2018.

- See, e.g., Brian Lambert, “The mystery of MintPress News,” MinnPost, November 11, 2015; Luke O’Brien, “Who Gave Neo-Nazi Publisher Andrew Anglin A Large Bitcoin Donation After Charlottesville?” Huff Post, June 12, 2019.

- Indictment, United States v. Netyshko, No. 1:18-cr-215 (D.D.C. July 13, 2018), Doc. 1, pp. 21-24 (“Netyshko Indictment”).

- See, e.g., Paul Wood, “Andy Khawaja: ‘the whistleblower’,” The Spectator, February 24, 2020.

- See Alberto Nardelli, “Revealed: The Explosive Secret Recording That Shows How Russia Tried To Funnel Millions To The ‘European Trump’,” Buzzfeed, July 10, 2019; SDNY, 2019; Angus Grigg, “Huang Xiangmo’s big night of gambling,” Financial Review, December 12, 2019; Hurley, 2020.

- See Mueller Report, Vol. I, pp. 1.

- Laura Rosenberger et al., The ASD Policy Blueprint for Countering Authoritarian Interference in Democracies, Washington: The Alliance for Securing Democracy, June 26, 2018, pp. 22-23.

- See Fiona Hill and Clifford G. Gaddy, Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin, 2nd ed., Washington: Brookings, 2015, pp. 303-311; Shekhovtsov, Chapters 6-7; U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Background to “Assessing Russian Activities and Intentions in Recent US Election”: The Analytic Process and Cyber Incident Attribution, Washington, January 6, 2017; Rozhdestvensky and Badanin, 2019; Rozhdestvensky, et al., 2019.

- See Bowe, pp. 3-6; Brady, pp. 7.

- As of early 2016, U.S. intelligence agencies were focused on Russian clandestine funding of European parties. See Peter Foster and Matthew Holthouse, “Russia accused of clandestine funding of European parties as US conducts major review of Vladimir Putin’s strategy,” The Telegraph, January 16, 2016. Even after the 2016 election, the Mueller report concluded that Russia’s two principal operations against the United States were disinformation and cyberattacks, with the investigation not seeming to have exhaustively followed the money. See Mueller Report, Vol. I, pp. 1; Josh Rudolph, “Congress Should Follow the Money Like the British Parliament,” The German Marshall Fund of the United States, July 31, 2020.

- In a February 2020 memo to the states, U.S. officials warned of three possible offline Russian tactics not seen in 2016, all fitting within our definition of malign finance: financial support to candidates or parties, covert advice to political candidates and campaigns, and the usage of economic or business levers to influence a campaign or administration. See Eric Tucker, “US: Russia could try to covertly advise candidates in 2020,” AP News, May 4, 2020.

- See Juan Zarate, Treasury’s War: The Unleashing of a New Era of Financial Warfare, New York: PublicAffairs, 2013, ch. 1-4.

- See Elise J. Bean, Financial Exposure: Carl Levin’s Senate Investigations Into Finance and Tax Abuse, New York: Springer, 2018, pp. 66-80.

- SHIELD Act; AML Act; DISCLOSE Act; Honest Ads Act; PAID AD Act; United States Congress, H.R.1 – For the People Act of 2019, passed March 14, 2019.