Introduction

In the spring of 2016, as the Russian-domiciled First Czech Russian Bank (FCRB) approached insolvency, staff worked feverishly to erase ledgers, destroy documents, and conceal evidence of the bank’s activity over the previous 9 years. These documents, had they survived, would have revealed the details of a litany of questionable activities: financial support for Iran; use of the bank as a vehicle for money laundering by corrupt elites on a massive scale through the Russian Laudromat, a money laundering scheme identified by Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP); support for sanctioned organized crime figures; and most alarming of all, Russian state-sanctioned interference in the Western political system in the form of a 9.4 million euro loan to the National Front, a far-right French political party.1 While most documents attesting to these activities were destroyed,2 a more banal form of illicit activity—self-enrichment by the bank’s director—caused litigation over remaining assets and liabilities. Information released in that litigation offered investigators a rare glimpse into how a private Russian bank became a key cog in Moscow’s attempt to swing political contests overseas—and how this bank sought to use existing campaign finance loopholes to achieve political objectives.

In light of recent electoral interference posed by Russian public and private actors, US and European law enforcement have intensified scrutiny of Russian financial support for foreign political actors in Western political systems. Despite this attention, relatively few instances of direct Russian financial interference in the political processes of other countries have been reported in the media. It is thus imperative to carefully study the known instances of Russian financial support for foreign political actors in order to identify the nodes and pathways facilitating these financial flows. Of these few instances, the FCRB’s 9.4 million euro loan to the National Front is perhaps the best known. The loan, unlike many other instances of Russian political finance, was channeled through formal financial mechanisms, rather than opaque or criminal pathways. But while the funding of the National Front did not involve sophisticated money laundering or outright bribery, the use of a private bank nonetheless provided a layer of deniability, shielding the involvement of senior Russian government officials who had helped to arrange the loan.

Adhocracy in Action

The phenomenon of senior officials using private entities to carry out national policy goals is not unusual in Russia. The wealth or business connections of private actors in Russia are often opportunistically leveraged, with varying levels of direction by the state, to achieve core state goals both at home and abroad.3 Besides keeping costs low, this approach gives Moscow access to a suite of tools and capabilities that public sector bodies may be unable to wield, as well as a crucial layer of deniability should things go wrong.4 At the same time, efforts channeled through private entities can be kept in line through the ample coercive powers, both formal and informal, wielded by the state.5

The FCRB loan to the National Front proceeded along these lines. An opaque, ad hoc network of high-level political figures arranged this political financing effort which leveraged the FCRB, a private entity trusted by Russian elites, to provide financing to National Front (transferred via its correspondent account at the Austrian Raiffeisen bank).6 When the FCRB entered bankruptcy proceedings, the network did not abandon the National Front loan. Instead, they temporarily transferred the loan to a shell company and then turned to another private entity trusted to deliver on sensitive goals on behalf of the Russian state—Aviazapchast JSC—an aviation company involved in high-priority strategic partnerships for the Russian state, including exports to the Syrian Ministry of Defense.7 This reaction, of temporarily shifting the loan first to a shell company and then to a trusted strategic node, illustrates the process of mobilizing (and, when necessary, replacing) private entities to further state political goals.

However, subsequent developments showed that this mobilization was not coordinated across the entire Russian government: later, the Deposit Insurance Agency (DIA), the Russian government agency responsible for ensuring bank deposits, sued the former bank management for the initial transfer, leading to a public court case.

Loan Arrangement

The FCRB loan was reportedly arranged as a result of extended contacts between the National Front’s representatives and affiliates of Alexander Babakov, a senior member of the Russian Federation Council (the upper chamber of Russia’s legislative assembly). Mr. Babakov wields a portfolio that includes national security and foreign affairs.8 Media reporting and leaked email correspondence indicate a pattern of in-person meetings and extensive communication between Jean Luc Schaffhauser, a National Front Member of the European Parliament, and Babakov representatives Alexander Vorobiev and Mikhail Pilsyuk.9 These meetings resulted in significant coordination on messaging, to the extent that Russian officials were supplying statements on the conflict in Ukraine to Marine Le Pen, the leader of the National Front.10

While Russian officials reportedly set the goals and made the arrangements, private actors at the FCRB and in French politics were called upon to carry them out in an arrangement that mirrors the “adhocracy” behind other Russian influence efforts.11 Initially, Schaffhauser, Vorobiev, and Pilsyuk, along with the National Front’s treasurer, allegedly first considered a French NGO controlled by Schaffhauser as the conduit for receiving Russian financing;12 however, the decision was ultimately made to furnish the money through FCRB to the party directly. Two other Russian banks were also considered, but in the end FCRB alone was selected.13 This may have been for a number of reasons. Clearly, FCRB and its ownership maintain important political ties with elements of the Russian government. FCRB’s historic activities, detailed below, suggest that it may have long been leveraged for both illicit finance and geopolitical purposes by members of the Russian elite, and was therefore entrusted to engage in strategic political finance as well.14 In addition, under a quirk of French electoral law, FCRB could provide the National Front with a loan, even as a foreign entity. in lieu of a donation. Direct donations to political candidates and parties from foreign persons are prohibited in France; loans from foreign entities are permitted.15 Moreover, if a candidate receives more than 5% of the vote, half of their campaign costs are reimbursed by the French state; thus a larger loan could be taken by a candidate in order to get above this threshold.16 That candidate’s success would ease repayment of the loan.17 Motives of self-enrichment may also have played a role, as FCRB reportedly gave Schaffhauser a 140,000 euro commission for arranging the loan, paid to a consulting company controlled by his wife.18

Image 1: Alexander Babakov addressing the Russian Federation Council in 2017. Source:http://council.gov.ru/events/multimedia/photo/61399/

The Bank

Originally designed to service Russian imports and exports with Europe, the bank was also known to facilitate trade with Iranian clients while Iran was under US and international sanctions, and allegedly held funds for the Central Bank of Iran.19 The FCRB was formed as an independent entity in 2007 when Roman Popov, a wealthy Russian businessman, purchased the bank as a unit from Stroytransgaz, a Russian energy company where Popov had been an executive.20 When the FCRB received a banking license in the Czech Republic in 2008, it became one of the few Russian-owned financial institutions to gain a license in the EU.21 It did so via a Czech subsidiary, the International Cooperation Bank, which was later renamed as the Evropsko-Ruska Bank and commenced operations in 2009.22 The licenses of both the Russian parent and the Czech subsidiary were later revoked by their respective regulators in 2016 after the FCRB entered insolvency proceedings.23 The Czech National Bank explicitly cited anti-money laundering violations when it revoked ERB’s license 24

The Bank’s Owner: Roman Popov

Roman Popov. Source: Press Service of the First Czech Russian Bank.

Roman Popov was reportedly the controlling figure for FCRB, serving as both majority shareholder and Chairman of the Board. Popov acquired the bank in 2007 from Stroytransgaz, where he was previously an executive. In addition to owning a strategically important bank and a network of companies, Popov chaired the Russo-Iranian Business Council, and reportedly owns high-value properties in Croatia and Russia.25

Popov also reportedly controls a network of companies in the Czech Republic, central Europe and other offshore jurisdictions, many of which appear related to companies that received loans from the bank that were never repaid. Reports and interviews indicate that Popov was personally involved in the operations of the bank, including warning certain clientele of the bank’s tenuous position in January 2016.26 While the bank and its subsidiary have had their licenses revoked, a network of private companies linked to Popov appears to remain active.

According to a source who claims to be close to him, Popov has traveled to the Czech Republic since the FCRB entered administrative proceedings in Russia, though he reportedly has severed ties with the bank.27 In April 2018, the Investigative Committee of Russia issued international arrest warrants for Popov and a key deputy for embezzling approximately $6.5 million USD.28

Illicit Financial Flows

In addition to serving as a conduit for Russia-Iran business, the FCRB was also allegedly a key node and pathway for illicit financial flows. FCRB was one of 19 Russian financial institutions implicated in a $20 billion capital flight and laundering scheme that moved money out of Russia into European accounts through Moldova and Latvia between 2011 and 2014, known as the Russian Laundromat.29 30According to OCCRP’s data, FCRB sent at least $126 million through the Laundromat from Russia.31 FCRB’s involvement in this scheme indicates that while in operation, the bank likely served as a key node for Russian illicit financial flows before issuing the loan to the National Front.32

The FCRB’s broader role as a key pathway for strategic Russian financial flows to the Western political system only became visible in the open source when the bank entered bankruptcy proceedings, offering rare insights into the assets and wider connections of a bank that played a key role in Russian political financing.

Financing Projects Linked to Sanctioned Individuals: Ruben Tatulian

Tatulian opening the mall near Sochi supported by the First Czech Russian Bank. Source: Channel EFKATE (Телеканал ЭФКАТЕ)

The FCRB has also allegedly been used to facilitate the activities of Russian organized crime groups, including those of sanctioned individuals such as Ruben Tatulian, who was designated by the US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) in December 2017 for “providing

material support to the Thieves-in-Law,” a Eurasian organized crime group.33

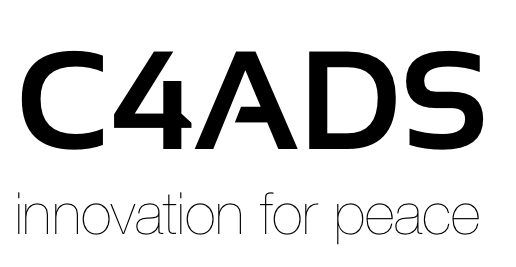

Tatulian was directly involved in business with the FCRB as well as Popov, its chairman. Roman Popov became a 25% owner of the R-7 Group LLC (ООО Эр Севен Групп) (“R-7 Group”) with Ruben Tatulian in June 2011.34 One month after Popov gained a minority stake in the firm, the First Czech Russian Bank issued R-7 Group a €30.5 million loan.35 According to Popov, FCRB also assisted R-7 Group in attracting financing from another Czech bank and supplying technology for a mall project located near Sochi, completed in 2013.36 The mall was personally opened by Tatulian in a ceremony that Popov attended.37

According to the OFAC press release accompanying Tatulian’s 2017 designation, he “was appointed as the ‘overseer’ of the Sochi, Russia Thieves-in-Law operation run by a senior Thief-in-Law.”38 Additionally, OFAC claims that Tatulian has assisted thieves-in-law who encountered legal problems on multiple occasions.39 In addition to personally sanctioning Tatulian, OFAC also designated two companies he allegedly controlled: Novyi Vek—Media, LLC (ООО Новый Век—Медиа) and Vesna Hotel and Spa Ltd. (ЗАО Спа-Отель Весна).40 Tatulian previously directly owned and claimed to be president of the R-7 Group.41

Popov is involved in corporate arrangements which tie directly back to Tatulian and his sanctioned companies. Popov and Tatulian allegedly jointly own a British Virgin Islands firm, Royaline Investments Ltd., in order to hold indirect shares in R-7 Group.42 R-7 Group’s ownership is layered through two firms in the Czech Republic, one of which is Dastyno Commerce S.R.O.43 Dastyno Commerce previously had two 50% shareholders: Novyi Vek–Media, owned fully by Tatulian, and Royaline Investments.44 The 50% held by Royaline was given to Royaline as collateral for a 2011 €11.9 million loan from FCRB to a Cypriot firm with no visible activity, Laerma Limited.45 Laerma’s loan was due to be paid back by June 2016, but according to the DIA’s records, the loan payments are overdue and the accrued interest remain unpaid.46

Figure 1: R-7 Group LLC corporate network.

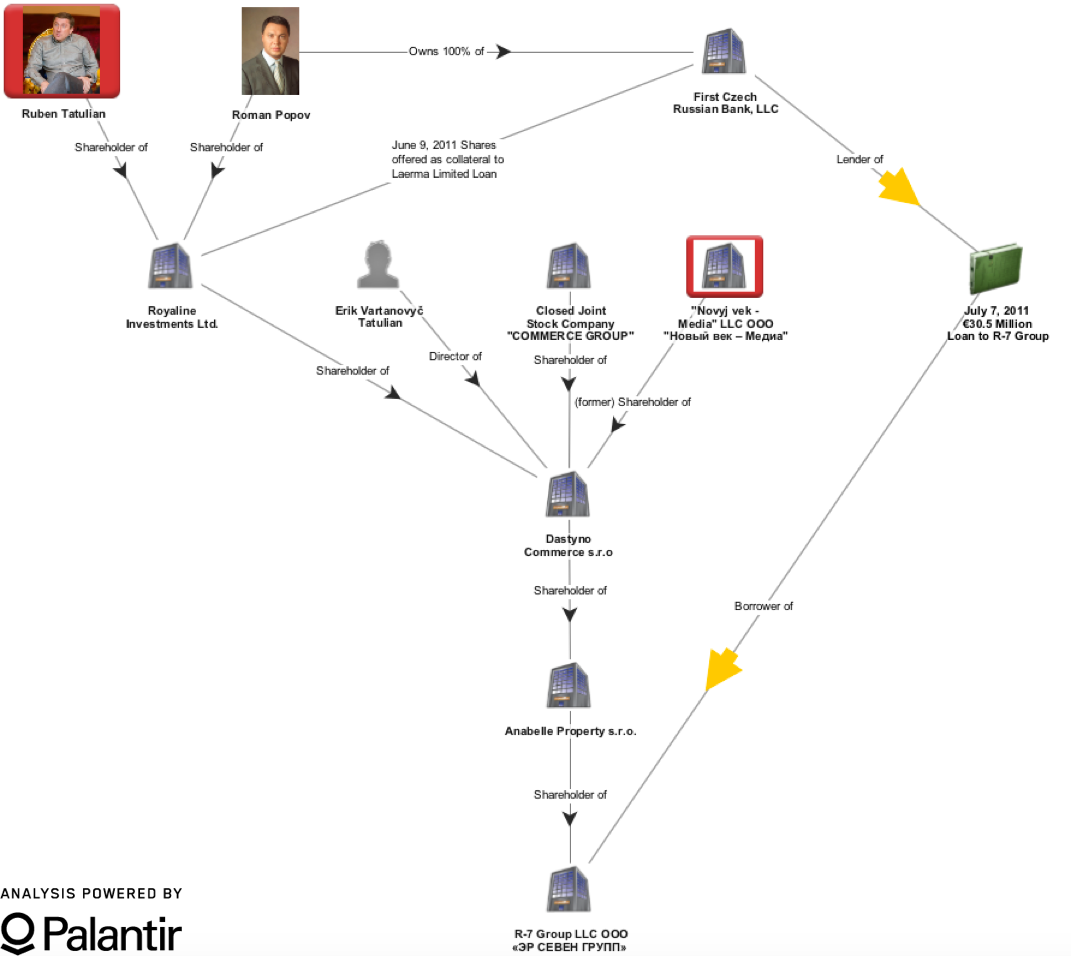

Bank Deterioration

While Schaffhauser, Babakov, and their associates successfully arranged the National Front loan and kept its terms largely secret, they likely did not account for the potential failure of the FCRB. The bank became insolvent in March 2016 and remains embroiled in a number of lawsuits and more recently, criminal investigations.47

In the week before the bank was declared insolvent, management engaged in 32 financial operations to forgive debts, sell assets, and transfer funds; the DIA later contested these transactions in court as invalid.48 According to Russian media coverage, Popov and the bank’s management began to warn certain priority clients in January 2016 that the bank was distressed to allow them to move their money.49 Another politically sensitive client permitted to transact in the final days of operation was Arsenal Invest LLC (ООО Арсенал Инвест), a firm owned entirely by Aleksandr Yanukovych, son of ousted Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych.50

Loan Data Destruction

In addition to the financial activity by the bank’s management in the week preceding administration, the credit database of the bank was also allegedly destroyed.51 This unusual state of affairs was reflected in the inventory taken by DIA prior to public auction of the bank’s assets. DIA identified more than $125 million worth of loans to entities whose data were absent from the bank’s ledgers.52 Of the 43 debts issued where information was missing, nine were loans to foreign companies and a further 18 debts were interest payments on loans dating back to 2012.53

Loan Transfers: «Pure Business»

Since the insolvency administration took over, lawsuits and bank asset auctions have laid bare a significant portion of the bank’s clientele and lending practices, including details concerning the National Front loan which shed light on the networks involved in the formation and transfer of the loan. Shortly before the bank failed, the National Front loan was transferred for unknown reasons first to a shell company, Konti LLC (ООО Конти), then again to Aviazapchast JSC (АО Авиазапчасть), an aviation company involved in high-priority strategic partnerships for the Russian state, including exports to the Syrian Ministry of Defense.54

Why the National Front loan was transferred remains unclear. The DIA’s suits to recover funds transferred during the 32 financial operations undertaken just before the bank’s failure have revealed key details about the activities, but not the reasoning behind them. Indeed, when Russian journalists asked Sergei Yeseyev, Konti LLC’s director and sole shareholder, why he decided to acquire the National Front debt, Yeseyev claimed it was “pure business.”55

Examination of Konti’s 2016 balance statement indicates that the company operates with relatively little overhead or profits, while engaging in a substantial amount of borrowing and lending – a classic indication that this is likely a shell company without physical operations (which is not in and of itself damning, as this practice a common one among professional investment firms).56 Given that court records have revealed that Konti spent close to 4000 times its 2016 revenue to acquire the National Front loan, though, Konti’s activities and sources of financing may be worthy of closer scrutiny.57 The owner of Konti, Yeseyev, also directs three other Russian firms. One of the firms, Private Security Firm “A-5” LLC (ООО ЧОП А-5), was previously owned by the Czech Russian Leasing Company LLC (ООО Чешско-Русская Лизинговая Компания). A-5 had previously been owned by the FCRB, and is currently owned in part by the bank’s owner, Roman Popov, indicating that the bank’s management may have a relationship with A-5’s current director.58 In addition to purchasing the right to National Front’s 9.4 million euro debt, Konti and A-5 engaged in three other transactions with the troubled FCRB that the DIA is contesting in court as invalid.59 The court cases have not revealed the reason for why the loan was first transferred to Konti; however, Aviazapchast, the second firm which acquired the debt after Konti, may indicate further Russian state interest in ensuring the continued servicing of the loan.

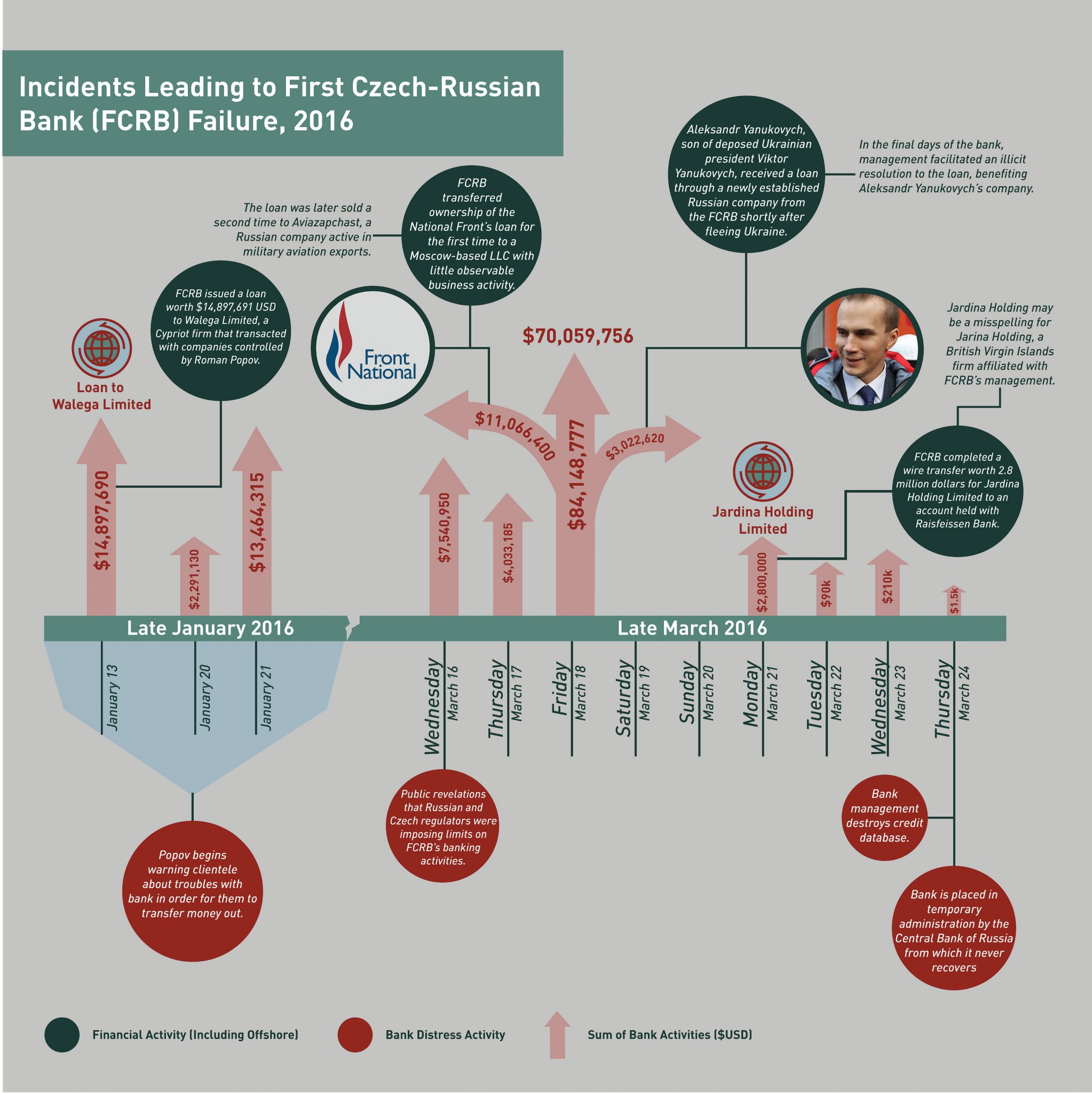

Aviazapchast: Convergence between political and military industrial finance

Aviazapchast was formed from “Aviazagranpostavka,” a Soviet company which serviced aircraft exported from the Soviet Union; today, Aviazapchast’s line of business is fairly similar, concentrating on the export and servicing of Russian aviation equipment and spare parts. Although a private company, Aviazapchast is trusted to achieve significant Russian state objectives, such as servicing and supplying a number of foreign militaries including those of Sudan, Algeria, India, and other Russian allies.60 Additionally, Aviazapchast provides direct material support to the Syrian Ministry of Defense and Syria Arab Airlines,61 both sanctioned by OFAC for their respective roles in the Syrian conflict.

Aviazapchast’s reported foreign countries of business in 2017. Source: Aviazapchast 2017 Annual Report.

Several of Aviazapchast’s personnel have been reported to have links to the Russian intelligence services. Vice Director and board member Yevgeniy Barmyantsev served several years in the Russian intelligence services, including serving as the assistant to the military attaché in the United States from 1977-1983.62 Barmyantsev went on to serve in Syria and Yugoslavia before assuming a leadership position at the Moscow headquarters of the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence agency.63 Aviazapchast’s former accountant, Tatyana Lityagina, is the sister of the head of FSB’s Economic Security Service, which is responsible for the fight against organized crime in Russia.64 Valery Zakharenkov, the company’s sole shareholder, has been involved in the illegal sale of Russian arms abroad, including the sale of 3 Russian Su-22 fighter planes in Yemen. These transactions were made with the assistance of Yuri Makarov,65 a notorious arms dealer and former Lieutenant Colonel in the Russian Air Force who was later sued by his FSB business partners.66 In addition, despite Aviazapchast being a private company, in 2014 its Paris office was refitted by Russia’s “Roszagransobstvennost,” which is responsible for the maintenance of overseas Russian state territory.67

The reasoning behind Aviazapchast’s acquisition of the loan remains opaque. The company does not claim to engage in trade in financial instruments such as loans, and this action was not listed in the company’s 2016 annual reporting with regards to significant business actions. The company listed four major transactions for the year, all of which were approved by the company’s sole shareholder, Zakharenkov. Two of these transactions were made ten days before the loan was acquired by Aviazapchast.68 Given Zakharenkov’s active management of other decisions within the company, it is reasonable to conclude that the shareholder himself took the decision to acquire the politically sensitive loan. Indeed, the outstanding value of the loan was roughly equal to Aviazapchast’s total pre-tax profit.69 This may indicate that this action could have come at the behest of state actors or the originally arranging network.

Conclusion

The collapse of the First Czech Russian Bank offers a unique window into a number of Russian illicit networks and financial flows. The bank was simultaneously moving money for the Russian Laundromat, financing organized crime figures, even as money was spirited out of the bank using loans as vehicles.

In May 2018, the lawsuit over the National Front debt was resolved in favor of the transferees.70 The National Front is now obliged to make its loan repayments to a firm providing equipment for use by the Syrian Air Force and the Syrian regime airline sanctioned for acting on behalf of the Iran Revolutionary Guard Corps. The loan arrangement and subsequent transfer displayed the extent to which Russian actors will opportunistically leverage nodes of other Russian financial networks, including criminal and strategic financial nodes. Given that key illicit nodes are brought in occasionally to participate in political finance schemes, it is imperative for law enforcement and regulatory bodies to scrutinize these entities for illicit activity closely, which in turn will mitigate some of the political activity.

While the suit was settled in the transferees’ favor, the fact that the suit proceeded publicly speaks to the ad hoc nature and limited power of the network that arranged the loan. The Russian entities that arranged the financing were not able to intervene to prevent the bank’s failure or the public legal clash which revealed details of the political financing. While powerful individuals within Russia worked to secure and facilitate the financing, it seems as though many parts of the Russian government did not actively work to conceal the loan.

Ongoing lawsuits in Russia may reveal further information on the bank’s activities; however, in many cases the defendants have yet to appear in court. It is clear that the First Czech Russian Bank and its subsidiary engaged in a variety of suspicious financial practices. The Russian and Czech central banks cited widely different reasons for revoking the licenses of FCRB and its subsidiary.71 72 The Central Bank of Russia cited poor credit risk assessment and inadequate capital ratio for its action against First Czech Russian Bank, while the Czech National Bank revoked the license of Evropsko-Ruska Banka for multiple reasons including the lack of a functioning control system to prevent money laundering, terror finance, and sanctions compliance.73 74

Other banks with organized crime ties and weak compliance controls have frequently demonstrated willingness to service a variety of other illicit financial flows. The millions of dollars in lost assets, financing of Russian organized crime, and political loans are only part of the bank’s portfolio.75 What remains are the other clients who kept and moved their money using the bank and have likely relocated their operations.

- https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/2955017?from=doc_vrez. For evidence that the bank was used to launder money for

the Russian elite, see, inter alia, https://www.rbc.ru/finances/21/03/2017/58d11ee39a79472280f0c9ee; https://www.occrp.org/

en/laundromat/; https://www.occrp.org/en/laundromat/the-russian-laundromat-superusers-revealed/. - https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/2955017?from=doc_vrez.

- The literature on this phenomenon is extensive. For the use of organized crime networks abroad, see https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/crimintern_how_the_kremlin_uses_russias_criminal_networks_in_europe. For the use of oligarchs as tools of state policy, see https://www.csce.gov/sites/helsinkicommission.house.gov/files/Kleptocrats.pdf. For the subornment of nominally private civil society groups, see https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/field/field_document/20141024RussianInfluenceAbroad.pdf.

- https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2017/07/21/538535186/in-putins-russia-an-adhocracy-marked-by-ambiguity-and-plausible-deniability

- See https://www.csce.gov/sites/helsinkicommission.house.gov/files/Kleptocrats.pdf at 6.

- Document held by author.

- http://www.aviazapchast.ru/upload/god_otch_16.pdf

- http://kremlin.ru/events/president/news/15675; http://www.er-duma.ru/party/profile/49446/

- https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/020517/la-vraie-histoire-du-financement-russe-de-le-pen?onglet=full; http://www.interpretermag.com/russia-and-front-national-following-the-money/

- https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/020517/la-vraie-histoire-du-financement-russe-de-le-pen?onglet=full.

- https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/controlling_chaos_how_russia_manages_its_political_war_in_europe

- https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/020517/la-vraie-histoire-du-financement-russe-de-le-pen?onglet=full

- The two other banks reportedly considered were Strategy Bank and Commercial Bank NCB. See https://www.occrp.org/en/component/content/article?id=6413:latvian-consultant-allegedly-helped-marine-le-pen-s-party-obtain-russian-loan.

- https://jamestown.org/from-tanks-to-spies-to-banks-the-european-russian-bank/

- See Avis No. 392602 of the Conseil d’État, available at http://www.conseil-etat.fr/Decisions-Avis-Publications/Avis/Selection-des-avis-faisant-l-objet-d-une-communication-particuliere/Financement-campagnes-electorales.

- See http://www.cnccfp.fr/docs/campagne/20161027_guide_candidat_edition_2016.pdf section 1.4.

- http://www.dw.com/en/french-elections-who-finances-the- candidates/a-38704682; https://www.loc.gov/law/help/campaign-finance/france.php#f27.

- https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/261114/le-fn-attend-40-millions-deuros-de-russie?onglet=full.

- https://www.tyden.cz/rubriky/byznys/cesko/prvni-cesko-ruska-banka-ziskala-licenci-v-cesku_54933.html; https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303299604577323601794862004.

- The bank was acquired and reorganized in 2007 by Roman Popov from Stroytransgaz. It had previously been jointly owned by the Investment and Postal Bank of the Czech Republic and Revival Bank of Russia. For more history of the bank see: https://www.banki.ru/banks/memory/bank/?id=9038724. Storytransgaz is a construction conglomerate that builds oil and gas extraction infrastructure. Gennadiy Timchenko is the majority shareholder of the company. Both Timchenko and Stroytransgaz are sanctioned by the U.S. Department of Treasury under E.O. 13661. See: https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press- releases/Pages/jl23331.aspx and https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl2369.aspx.

- https://byznys.ihned.cz/c1-36595720-prvni-cesko-ruska-banka-otevre-sidlo-v-praze; http://ptel.cz/2016/07/bremya-dengi/.

- https://byznys.ihned.cz/c1-36595720-prvni-cesko-ruska-banka-otevre-sidlo-v-praze; http://ptel.cz/2016/07/bremya-dengi/.

- https://www.reuters.com/article/us-czech-erb-idUSKCN12O114; https://en.crimerussia.com/financialcrimes/first-czech-russian-bank-management-wanted/, https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/3600260

- http://www.cnb.cz/cs/verejnost/pro_media/tiskove_zpravy_cnb/2016/20161024_erb_bank_licence.html.

- http://arhiva.nacional.hr/clanak/86706/tajanstveni-ruski-bogatasi-u-najljepsim-kvarnerskim-vilama; https://russiangate.com/nedvizhimost/zelenaya-loshchina-zemli-deputatskogo-naznacheniya-/; https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303299604577323601794862004

- https://www.gtreview.com/news/europe/new-russian-bank-secures-first-for-europe/; https://rg.ru/2014/12/09/popov.html; https://www.rbc.ru/newspaper/2016/03/28/56f512289a7947a3e3abe2e2.

- https://www.rbc.ru/newspaper/2016/03/28/56f512289a7947a3e3abe2e2.

- https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/3600260.

- The Russian laundromat moved money by setting up fake loans between shell companies mostly incorporated in the UK. These contracts were then guaranteed by a Russian company and a Moldovan citizen in a Moldovan court. Then the debtor defaulted on the contract. The matter was then referred to a Moldovan court, where corrupt judges would enforce the contract and appoint a judicial executor. The executor, involved in the scheme, arranged for the guarantor to send the money to an account in Moldova, from where it frequently traveled to accounts in Lativa before filtering into the global financial system. For further details see: https://www.occrp.org/assets/laundromat/laundromat-infographic.png & https://www.occrp.org/en/laundromat/the-russian-laundromat- exposed/; https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/20/the-global-laundromat-how-did-it-work-and-who-benefited; https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/20/how-dirty-money-from-russia-flooded-into-the-uk-and-where-it-went; https://www.occrp.org/documents/laundromat-companies.xlsx.

- https://www.novayagazeta.ru/articles/2014/08/21/60821-171-landromat-187

- https://www.occrp.org/documents/laundromat-companies.xlsx.

- https://www.occrp.org/en/laundromat/the-russian-laundromat-exposed/

- https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0244.

- Document held by author. Dastyno Commerce, Anabelle Property, and R-7 Group Registries.

- Document held by author. R-7 Group Loan Auction Document.

- http://efcate.com/show_news__/2013/06/10/171016 ; https://rg.ru/2014/12/09/popov.html.

- http://efcate.com/show_news__/2013/06/10/171016.

- https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0244.

- https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0244.

- https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/OFAC-Enforcement/Pages/20171222.aspx.

- http://efcate.com/show_news__/2013/06/10/171016; Video held by author. Document held by author.

- Document held by author. Royaline Investments 2014 Certificate of Incumbency.

- Documents held by author.

- Document held by author. Dastyno Commerce’s current shareholders are Royaline Investments and an Armenian firm, Commerce Group, that is in liquidation in Armenia.

- Documents held by author. Laerma Limited Loan Agreement.

- https://www.asv.org.ru/liquidation/news/453613/

- https://www.rbc.ru/society/12/04/2018/5acec7a89a7947a5e31bfbcd.

- https://www.asv.org.ru/liquidation/news/432053/; https://www.asv.org.ru/liquidation/news/439341/; https://www.asv.org.ru/liquidation/news/467450/; https://www.asv.org.ru/liquidation/news/510439/.

- https://www.rbc.ru/newspaper/2016/03/28/56f512289a7947a3e3abe2e2.

- Document held by author. Arsenal Invest was opened in St. Petersburg in May 2014 shortly after Aleksandr Yanukovych fled Ukraine and received a $5.66 million loan in August 2014, approximately a month before the National Front loan was issued. https://www.fontanka.ru/2014/11/14/154/

- https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/2955017?from=doc_vrez.

- https://www.asv.org.ru/liquidation/news/453613/.

- https://www.asv.org.ru/liquidation/news/453613/

- http://www.aviazapchast.ru/upload/god_otch_16.pdf

- https://www.rbc.ru/rbcfreenews/587510ca9a794741909b632a; According to ROSSTAT, the company’s primary revenue streams were the receipt and dispensation of loans, with credit-assets amounting to nearly $35 million and liabilities of nearly $38 million in 2016. Konti LLC also lost just over $2 million in 2016. Documents held by author.

- Konti is capitalized at 10,000 rubles (approximately 161.80 USD at current rate) and does not list any fixed assets in its 2016 balance statement. Additionally, in 2016 Konti reported less than 5 thousand dollars in revenue, while it had more than 30 million dollars in total balance, indicating that it is likely engaged in substantial lending and borrowing practices relative to the company’s size.

- Konti 2016 Annual Balance Statement

- Documents held by author.

- See Court case: А40-148779/2016. See also https://www.asv.org.ru/liquidation/news/432053/; https://www.asv.org.ru/liquidation/news/439341/; https://www.asv.org.ru/liquidation/news/467450/.

- Documents held by author: Aviazapchast trade data

- Commercially Available Trade Data

- Commercially Available Trade Data; https://echo.msk.ru/blog/openmedia/2255160-echo/

- https://echo.msk.ru/blog/openmedia/2255160-echo/

- https://echo.msk.ru/blog/openmedia/2255160-echo/

- https://echo.msk.ru/blog/openmedia/2255160-echo/

- https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/210160

- https://echo.msk.ru/blog/openmedia/2255160-echo/

- Document held by author: 2016 Aviazapchast Annual Report

- Document held by author: 2016 Aviazapchast Annual Report

- https://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/180518/le-mystere-s-epaissit-autour-du-pret-russe-du-front-national?onglet=full. A Cassational appeal was filed in late 2018, which could yet overturn the previous decisions, or cause re-consideration of the case.

- http://www.cbr.ru/press/PR/?file=01072016_084057ik2016-07-01T08_37_18.htm.

- http://www.cnb.cz/cs/verejnost/pro_media/tiskove_zpravy_cnb/2016/20161024_erb_bank_licence.html.

- http://www.cbr.ru/press/PR/?file=01072016_084057ik2016-07-01T08_37_18.htm.

- http://www.cnb.cz/cs/verejnost/pro_media/tiskove_zpravy_cnb/2016/20161024_erb_bank_licence.html.

- https://www.asv.org.ru/liquidation/news/453613/; http://www.erbank.cz/images/PDF/Vyrocni-zprava-2015-CZ.pdf