Overview

On January 31, 2021, a new immigration route for British National (Overseas) (BNO) passport holders came into force in the United Kingdom. The BNO was a document created for Hong Kong citizens who wanted to maintain ties with the U.K. after the 1997 handover of the city. Under the new scheme, almost 5.2 million BNO holders and their dependents now have a path to full British citizenship after six years of residency in the U.K. Immediately after the U.K.’s announcement, the Chinese government, supported by the “wolf warrior” rhetoric of Chinese diplomats and state media, struck back against the British measure by launching a coordinated campaign to smear the British government.

By the Numbers

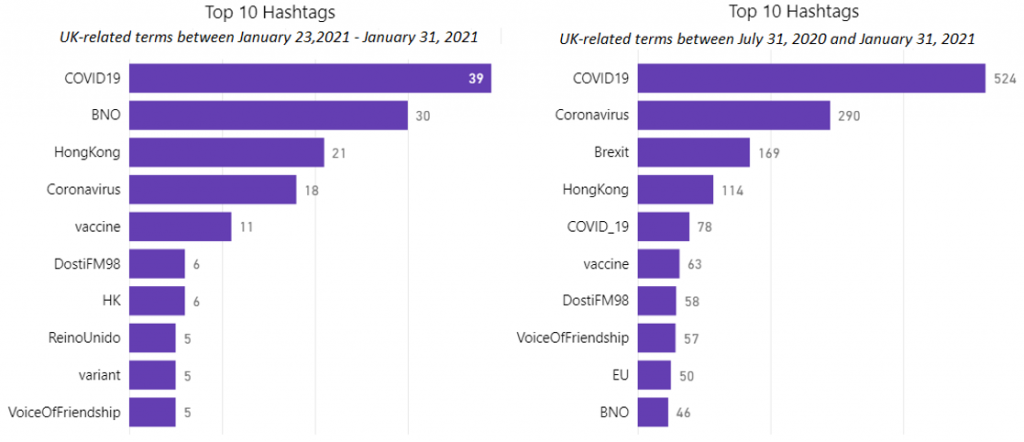

Between January 23 and January 31, 2021, the U.K. was the third most-mentioned country by Chinese government and state media Twitter accounts monitored on the Hamilton 2.0 dashboard, with over 400 mentions. “BNO” and “Hong Kong” were the second and third most frequent terms associated with U.K.-related tweets over that time period. More than half the tweets about BNO posted over the past six months were posted in the last ten days of January 2021.

Source: Hamilton 2.0 dashboard

Also apparent from the above comparison is the prominence of Brexit in U.K.-related coverage out of the Chinese propaganda apparatus over the last six months. Chinese diplomats and state media’s stance on Brexit changes depending on their objectives. While they can sometimes praise the U.K.’s renewed global ambitions, especially where they may translate to closer economic ties with China, the same voices will also use Brexit to portray the U.K. as isolated when, as in the case of the BNO immigration scheme, British authorities go against Beijing’s agenda.

Sources: Global Times (January 2021), Global Times (December 2020)

What We’re Seeing on Hamilton

Just as the new British immigration scheme was coming into force, the Chinese Foreign Ministry announced that it would no longer recognize BNO passports as valid travel documents. This was accompanied by efforts from Chinese diplomats and state media to delegitimize the documents, for instance by consistently referring to them as “so-called passports.”

Another recurring attack leveled against the British immigration plan was that it constituted an assault upon Chinese sovereignty and a “betrayal of trust” by the U.K. Nationalist tabloid Global Times summed up this point of view succinctly: “This act by the UK Britain [sic] severely infringes on the sovereignty of China, and it also blatantly interferes in the Hong Kong affairs and China’s internal affairs.”

Several diplomats and state media outlets took the accusations of interference one step further by presenting the U.K. measure as representative of a colonial mindset toward Hong Kong and its inhabitants. The spokesperson for the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office of the State Council reinforced this narrative by telling Xinhua that the U.K. move was “an attempt to turn a large number of Hong Kong people into second-class British citizens.”

Sources: T-House (part of CGTN), Chinese ambassador to Qatar

Finally, there is also a more threatening undercurrent coursing through much of the Chinese discourse aimed at the U.K. While CGTN observed that “London’s future as a banking center has dimmed with an ill-thought out Brexit” whereas “China’s [GDP] has risen 14-fold,” the Global Times more bluntly warned that “London is asking to be humiliated if it cannot tell the trend of the times and engages in political shows that provoke China.”

Why It Matters

Sino-British relations are at a crucial juncture. The U.K. fully departed the European Union over a month ago, and the Chinese propaganda apparatus wants to present the country as isolated and waning. With London adopting increasingly assertive measures towards Beijing over its Hong Kong national security law, human rights abuses in Xinjiang, and national security concerns over Chinese participation in British 5G infrastructure, China is likely to ramp up the pressure on the U.K. This fits a recent pattern of China lashing out at those it perceives as obstacles to its domestic and geopolitical ambitions. As recently as last December, for example, Australia bore the brunt of Chinese diplomats and state media’s “wolf warrior” rhetoric after a trade war sparked a war of words between the two countries. Now is the time for other democracies to express solidarity, lest they be next. The United States has already indicated its willingness to do its part in welcoming Hong Kong citizens fleeing political persecution. The U.K.’s European allies should do the same.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.