On June 18, Democrats on the House Intelligence Committee releasedaround 1,100 names of Twitter accounts linked to the Internet Research Agency (IRA), which is the official name of the Russian troll farm indictedby Special Counsel Robert Mueller for its attempts to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election. The new release brings the total number of known IRA-linked Twitter accounts to around 3,800. Analysis of the pages reveals that a major pillar of the Kremlin’s social media influence campaigns revolves around the impersonation of local news sources in order to gain trust among audiences and insert narratives into mainstream public discourse. This strategy of camouflaging disinformation channels as seemingly credible sources is even more prevalent in the IRA’s domestic efforts.

Twitter accounts linked to the IRA often impersonated local news sources in order to build credibility and sow disinformation narratives into targeted communities. Although all of the IRA-linked accounts were suspended by Twitter (and thus their content is no longer accessible), many of the pages are archived online, allowing for a glimpse into the IRA’s network of local news pages. For example, one account, @ChicagoDailyNew, has been preserved via the Wayback Machine digital archive, revealing that the page had accumulated over 19,000 followers in July 2016. @ChicagoDailyNew, which joined Twitter in May 2014, seems to have often tweeted links to legitimate news sources, likely to build credibility and expand its reach. Given the page’s large following, name, and graphics, users who viewed the account likely believed it was a legitimate local news source; however, the real Chicago Daily News closed down in 1978.

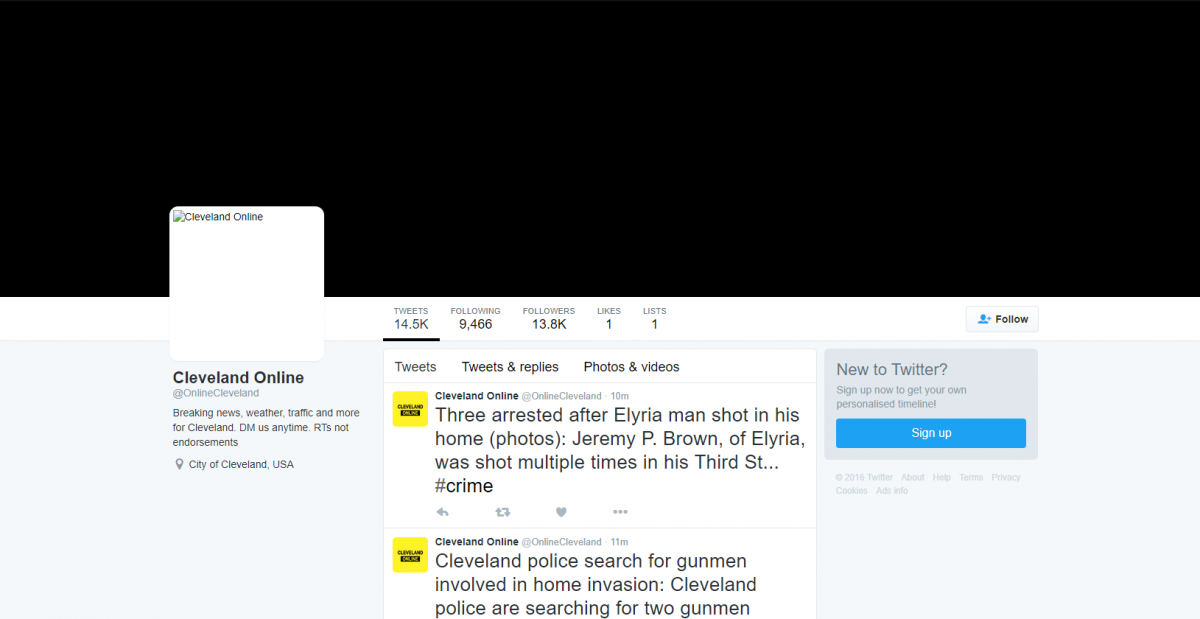

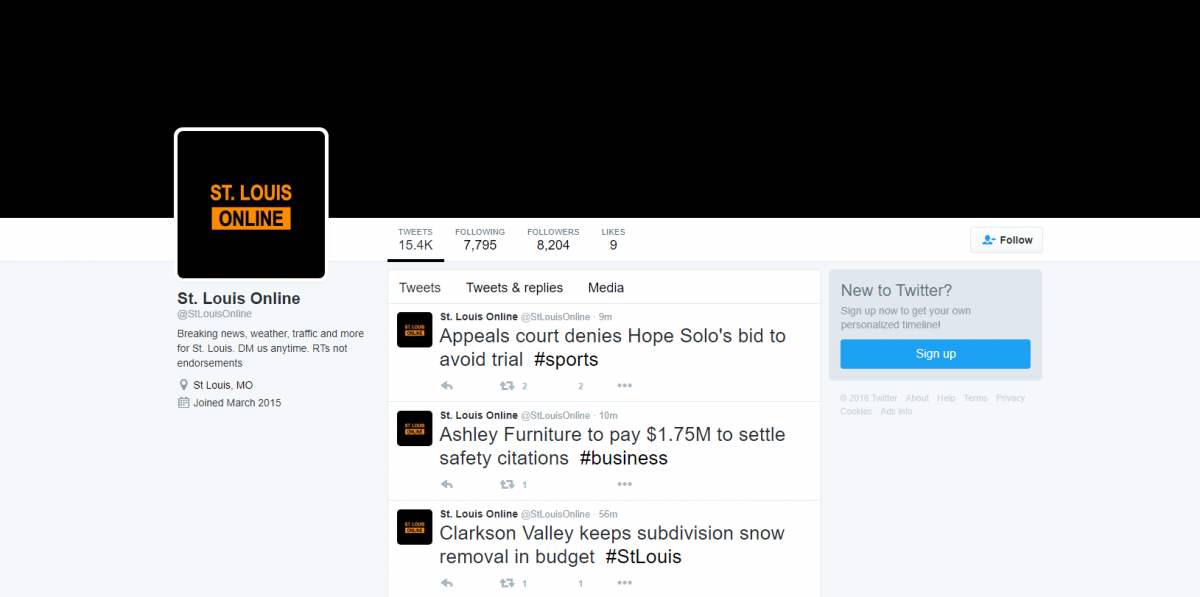

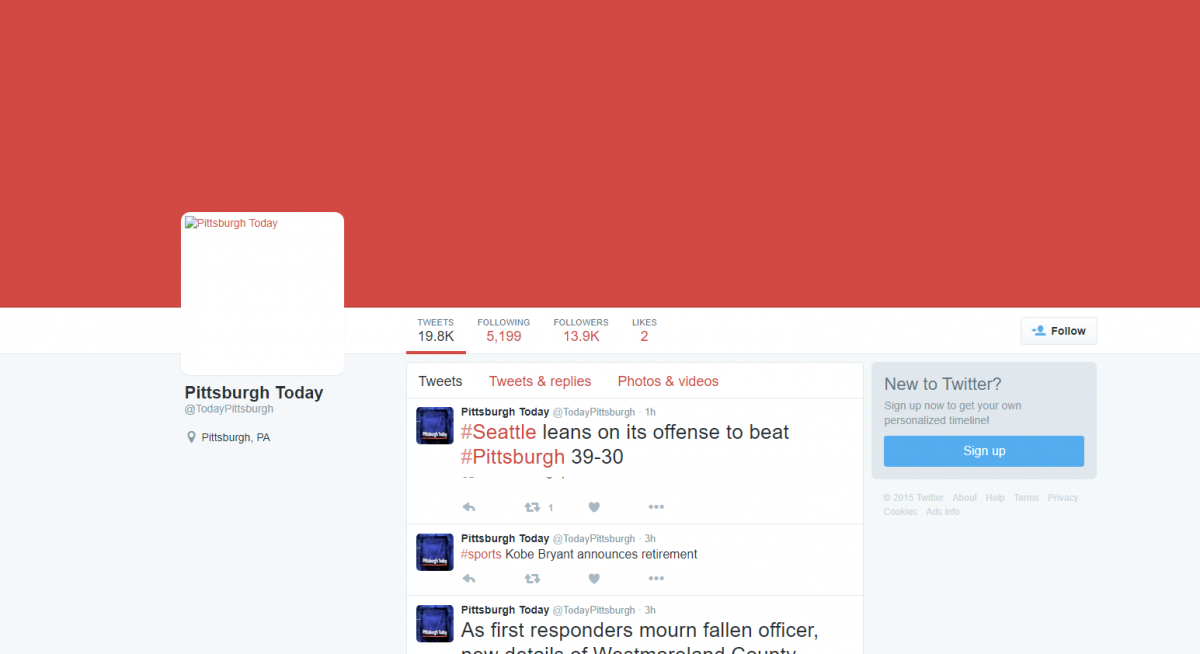

Other imitation news accounts used similar graphics and formatting to @ChicagoDailyNew, indicating that IRA employees likely used a template to construct numerous fake pages. These accounts also accumulated large followings, granting them substantial credibility and reach.

The imitation news accounts targeted a range of communities across the United States, often focusing on population centers and locations similarly targeted by the IRA’s Facebook ads campaign, such as Cleveland and St. Louis. The accounts tweeted up-to-date local news from these areas in order to build and maintain interest.

Other news accounts focused on specific social or political groups, including right-wing political organizations and African-American communities.

One common thread in the U.S.-focused news accounts is that they often posted regular local coverage and links to legitimate sources in order to build trustworthiness among followers. The accounts did not spew Kremlin disinformation from day one, but rather served as dormant sleeper cells, ready to be activated when the need arose.

A final and important takeaway is that the majority of the IRA’s imitation news accounts were not targeted towards U.S. audiences, but rather focused on the Russian-speaking online community. Similar to the U.S. accounts, these fake pages targeted Russians on a local level, impersonating news sources in various cities and regions (including in Ukraine and Crimea) in order to covertly control information flows. One account in the network, @NovostiSpb, gathered over 100,000 followers by imitating a St. Petersburg-based news source.

Although Western-based analysts and commentators often focus on the Internet Research Agency’s campaigns to undermine democracies abroad, it is necessary to remember that the IRA’s main function was always the manipulation of Russia’s domestic information space. Quite often, the tools used by the Kremlin to meddle in foreign countries are first tested at home. If Western democracies hope to defend themselves from authoritarian threats via the internet, they should begin by studying the mechanisms by which the Kremlin deceives its citizens at home.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.