The Energy Weapon is second in a six part series on Illicit Influence, published by the Alliance for Securing Democracy and C4ADS. The first part, A Case Study of the First Czech Russian Bank, can be found here.

Russia has a long history of using its control over European energy supplies to achieve political aims, and this “energy weapon” has become famous as a blunt instrument. According to the dominant image of Russia’s energy diplomacy, if states diverge from Russian foreign policy aims, the gas will be cut off in the dead of winter – as it was in Ukraine.

But in reality, the energy weapon is much more subtle, and much more effective at undermining Western states. The Russian government has learned to use energy to cultivate politically important relationships in consumer countries. At the same time, Russia uses its tools of asymmetric influence, including political interference and disinformation, in furtherance of its energy goals. This multi-faceted toolkit gives Russian policymakers more avenues to pursue their policy aims in the West, something missed when Russia’s energy diplomacy is thought of exclusively in terms of gas and oil cutoffs.

This case study goes beyond well-known instances of coercive Russian hydrocarbon diplomacy to examine how energy dominance is paired with deceptive corporate and financial obfuscation to undermine Western democracy, enrich elites, and achieve political ends. Examining case studies from several European countries, it highlights three relevant typologies that show how Russian energy politics go beyond pipeline power to include financial and other malfeasance:

· The use of energy delivery intermediaries, often based in Switzerland, to enrich favored elites in consumer countries;

· Russian use of energy firms to conduct political financing designed to influence the political affairs of consumer countries; and

· The pursuit of politically driven energy decisions in the fields of natural gas and nuclear power.

The aim of these tactics is to gain political leverage, often indirectly or through intermediaries and cutouts, in order to build long-term influence. Although they are easier to miss than crude gas cutoffs, energy-based relationships are arguably more important, as they create durable favorable constituencies, corrode democratic politics, and tie European countries to inefficient energy suppliers for the long run.

Russia has a long history of using its control over European energy supplies to achieve political aims, and this “energy weapon” has become famous as a blunt instrument. According to the dominant image of Russia’s energy diplomacy, if states diverge from Russian foreign policy aims, the gas will be cut off in the dead of winter – as it was in Ukraine.

But in reality, the energy weapon is much more subtle, and much more effective at undermining Western states. The Russian government has learned to use energy to cultivate politically important relationships in consumer countries. At the same time, Russia uses its tools of asymmetric influence, including political interference and disinformation, in furtherance of its energy goals. This multi-faceted toolkit gives Russian policymakers more avenues to pursue their policy aims in the West, something missed when Russia’s energy diplomacy is thought of exclusively in terms of gas and oil cutoffs.

This case study goes beyond well-known instances of coercive Russian hydrocarbon diplomacy to examine how energy dominance is paired with deceptive corporate and financial obfuscation to undermine Western democracy, enrich elites, and achieve political ends. Examining case studies from several European countries, it highlights three relevant typologies that show how Russian energy politics go beyond pipeline power to include financial and other malfeasance:

· The use of energy delivery intermediaries, often based in Switzerland, to enrich favored elites in consumer countries;

· Russian use of energy firms to conduct political financing designed to influence the political affairs of consumer countries; and

· The pursuit of politically driven energy decisions in the fields of natural gas and nuclear power.

The aim of these tactics is to gain political leverage, often indirectly or through intermediaries and cutouts, in order to build long-term influence. Although they are easier to miss than crude gas cutoffs, energy-based relationships are arguably more important, as they create durable favorable constituencies, corrode democratic politics, and tie European countries to inefficient energy suppliers for the long run.

Energy Interdependence

Russia and Europe are energy interdependent. Russia supplied more than 70 percent of natural gas and one third of all crude oil to OECD countries in 2016, which represented 75 and 60 percent of Russia’s exports in that year, respectively.1 These sales in turn were responsible for more than one third of the Russian budget for that year.2 Given the importance of energy production and export for Russia’s overall economic health, the central government has worked to retain significant control over the sector. Two significant levers in particular ensure that control is kept in the Russian government’s hands: first, Russia’s central government maintains a monopoly on the export of energy abroad. This gives Russia’s top policymakers direct control over energy supplies to several countries in Europe. Second, the Russian government can coerce nominally private Russian energy companies to behave in accordance with government policy aims. This gives the Russian government the ability to manipulate European energy trade to accomplish political aims, enrich chosen elites, and interfere with domestic political processes.

Energy Delivery Intermediaries: Opportunities for Elite Influence

Energy intermediary schemes make use of favorable trading arrangements to enrich key individuals or political parties in Western countries, in the hope that they will enact policies favorable to Russia. The schemes generally work as follows: Gazprom provides discounted gas to an authorized trading company to sell to national purchasers overseas at market rate, thus enriching the middlemen. Alternatively, Gazprom will sign a long-term delivery contract at a fixed price, and allow selected intermediaries to deliver using alternative routes at a lower price and cut into the Russian firm’s profits. Such schemes not only allow for direct, targeted payoffs, but also create captive constituencies favorable to Russian policies in the long term.

A recent example in Italy highlights one such alleged energy scheme in action: the Italian weekly L’Espresso has alleged that Russian government officials and Italian Interior Minister Matteo Salvini made plans for the secret funding of Salvini’s far-right La Lega party ahead of the May European parliamentary elections. At an October 2018 meeting in Moscow, Russian officials reportedly (per L’Espresso) offered to provide diesel to Eni, the Italian state oil company, at a 4% discount, using a Russian company linked to the sanctioned businessman Konstantin Malofeev. The proceeds generated from this differential would allegedly be kicked back to La Lega. The report remains uncorroborated, and the L’Espresso journalists could not confirm whether or not the deal went forward.34 This alleged arrangement also differed from other reported schemes in that energy was sold directly to a state energy company, rather than to an intermediary. Several similar intermediary schemes, though, have been widely reported in Bulgaria5, Hungary,6 Lithuania,7 Romania8, and Ukraine.9

Hungary

Between 2011 and 2015, a Hungarian intermediary scheme reportedly enriched elites aligned with Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s Fidesz party.10 MVMP, a subsidiary of Hungary’s state-owned electric company MVM, reportedly imported gas from a Swiss trader, MET International, allegedly to replenish Hungary’s strategic gas reserves.11 MET International was reportedly owned in part by MOL,1213 a Hungarian oil and gas company whose largest single shareholder is the Hungarian government14, alongside several Hungarians (one of whom is allegedly close to Orban)1516 and a Russian national, Ilya Trubnikov.1718 Several of the owners reportedly held their stakes via Cypriot shell companies.19

In a study of Russian influence in Hungary, Dániel Hegedűs reported that MET purchased Russian-origin gas cheaply on the spot market, sold it to MVMP, and then re-purchased the gas at a slight upcharge for transport using the Hungarian-Austrian gas Interconnector on the Hungarian side of the border.20 A ministerial decree reportedly authorized MET’s monopoly access to the pipeline.21 MET’s gas cost significantly less than the rate set by Gazprom’s long-term fixed contract to supply Hungary, but it was able to sell the gas domestically at market prices.22 The arrangement appears to have benefited the owners of MET at the expense of the Hungarian state budget. According to a February 2016 report by Dániel Hegedűs, this scheme relied on the informal consent of the Kremlin, as Gazprom controls gas re-sales in Europe.23 Hegedűs concluded that the scheme cut into Gazprom’s direct market share, and in his analysis the lack of Russian protest seemed to demonstrate the Kremlin’s tacit consent for favored Hungarian elites to enrich themselves with Russian gas.[15] In a single year, this scheme reportedly earned MET’s shareholders more than $200 million.24 Furthermore, investigative journalists allege that this scheme personally benefited top government officials including Orban himself.2526

Hungarian energy analysts claim that MET’s owners share close connections to two senior MOL figures, Zsolt Hernadi and Sandor Csanyi.27 Hernadi is the Chairman and CEO of MOL.28 Croatia issued a warrant for the arrest of Hernadi, alleging that he bribed the Croatian prime minister as part of an unrelated energy deal. Hungary refused Croatia’s extradition request.29 Csanyi, reported to be one of the wealthiest people in Hungary,30 is a member of MOL’s board.31 He serves as the CEO of OTP Bank,32 Hungary’s largest financial institution. Local reporting states that the bank’s two largest shareholders are MOL and a company owned by Megdet Rahimkulov, a billionaire businessman and former senior executive of Gazprom Hungary.33

Lithuania

In Lithuania, multiple intermediary firms have sold Russian gas to domestic consumers.34 One Swiss-based intermediary, LT Gas Stream, has drawn scrutiny as an opaque vehicle for selling gas on the Lithuanian market.35 A Lithuanian gas trader, Dujotekana UAB, abandoned a direct purchasing agreement with Gazprom in 2008 only to immediately commit to purchasing the same Russian gas through LT Gas Stream, a Swiss trader.36 LT Gas Stream is identified as a Gazprom subsidiary in a 2013 European Commission report on a Lithuanian LNG terminal despite reportedly being directly owned by a Cypriot firm, Restoni Trading Ltd.3738 The Swiss firm lists Edmundas Vilimas, a former lawyer for Dujotekana, on its Zug cantonal company registration.39 LT Gas Stream was allegedly granted discounted pricing from Gazprom while selling at market prices.40 The lack of transparency around LT Gas Stream makes it hard to determine whether the abrupt shift marks an attempt to enrich politically connected owners, who may be silent partners with Gazprom, the official owner.4142

Bulgaria

Bulgaria is, even relative to most its EU partners, very dependent on Russian oil and natural gas: according to Eurostat, as of October 2018 Bulgaria imports between 75-100% of both oil and natural gas supplies from Russia,43 a trend that has been mostly consistent for the past few years.44 In the 2000s, this gas importation involved an intermediary scheme between Gazprom and two companies: Overgas, Inc. and Wintershall Erdgas Handelshaus Zug AG (WIEE).45 Overgas was jointly held by Gazprom and UK-registered Overgas Holding Ltd and was linked to the Bulgarian businessman Sasho Dontchev.46 It is also reported that Gazprom held 50% of shares in WIEE, which was registered in Switzerland.47 After the 2009 Ukraine gas crisis, the Bulgarian government sought to work directly with Gazprom, and in 2012 the state-owned gas distributor Bulgargaz reportedly signed a ten-year contract with Gazprom.48

Gazprom reportedly sold its 50% stake in Overgas in 2016,49 and in the years since Bulgargaz’ deal with Gazprom the state energy company and its Russian supplier have apparently become involved in significant legal trouble at the national and EU level concerning its attempts to cut Overgas out of the Bulgarian energy industry.50 In its new partnership with the Bulgarian state-owned enterprise, the Bulgarian government apparently sought to: 1) eliminate Overgas as a competitor to Bulgargaz; 2) Revive the moribund South Stream and Bourgas-Alexandroupolis oil pipeline projects; and 3) prevent the Turkish Stream project, which bypasses Bulgaria, from going ahead.51

Ukraine

Throughout the late 2000’s, trading firms such as the Cypriot-Russian Itera, Hungary’s EuralTransGas (ETG), and the Swiss-based RosUkrEnergo (RUE) appear to have served as intermediaries brokering the sale of natural gas from Russia to Ukraine.52 The operations and incomes of these entities were extremely opaque, “with the true beneficiaries and shareholders obscured behind a complex international network of shell companies and offshore trusts.”53 ETG, for example, reportedly purchased gas from Gazprom in 2003 and immediately resold it to the Ukrainian firm Naftogaz Ukrayiny.54 This deal reportedly earned ETG an estimated $2 billion in revenue, while the firm paid Gazprom $425 million for transportation services.55 Yet the 30-person firm apparently only reported $220 million in profit that same year.56 The “missing” $1.3 billion is unaccounted for.57

Following ETG’s dissolution in 2004, the firm was replaced by the virtually indistinguishable and equally opaque RUE, half of which was owned by Gazprom and half by Centragas, a firm believed to be largely controlled by Ukrainian businessman and “friend of Putin” Dmitry Firtash.5859 According to claims made in a US racketeering case dismissed in 2019, Firtash and other beneficiaries of the intermediary scheme paid significant sums to Ukrainian politicians and public officials, demonstrating another threat posed by Russian-affiliated energy firms.60 Firtash went on to become “an important financier of the Party of Regions,” led by former President Viktor Yanukovych.61 Firtash is presently detained in Austria, undergoing extradition proceedings to the United States on bribery charges.62

Switzerland is the center of the global trade in commodities ranging from hydrocarbons to agricultural products, with a 42% global market share, according to a recent Swiss government report.63 Hundreds of companies, typically based in the cantons of Geneva and Zug, buy and sell commodities that never physically enter the country.64 This transit trade in natural resources is estimated to comprise as large a fraction of the Swiss economy as banking and asset management.65 While Swiss firms deal in commodities from around the world, the sector is notable for its important role in the brokering of Russian oil, gas, metals, and minerals sales.6667 Players vary: some are large multinational firms with diverse businesses, others are arms of Russian producers, and still others are small shops with limited or nonexistent public profiles.

The business is capital-intensive and relies on funding from large financial institutions. An advanced financial sector, a high standard of living, and favorable tax treatment have made Switzerland an appealing locale for commodities traders since the pioneering days of Marc Rich and Phillip Brothers.68 In those days, Switzerland was not obligated to adhere to the United Nations sanctions regime (though it voluntarily enforced these sanctions),69 and it did not become a full UN member until 2002.70

As the Zurich- and Lausanne-based NGO Public Eye has documented, the Swiss commodities trading sector presents major money laundering, illicit finance, corruption, and national security risk, as it is able to move billions of dollars related to strategically sensitive sectors in an opaque fashion.71 Public Eye has called on Switzerland to establish a regulatory and supervisory agency to oversee the sector.72 Switzerland is not unusual in failing to regulate the trade. The United Kingdom, the United States, Singapore, Hong Kong, and other jurisdictions likewise do not have agencies dedicated to regulating the trade in commodities, as opposed to derivatives or other financial instruments tied to the value of commodities. As Public Eye argues persuasively, Switzerland, having gained a dominant global position, has a moral and political responsibility to lead the way.73

Energy Firms’ Political Influence

Russian energy firms have financed political parties in Lithuania and Latvia, where a single firm formed by the manager of the local Lukoil subsidiary reportedly funded multiple political parties opposed to the entry of Western energy firms into local markets.7475 In Croatia, as detailed below, Russian firms reportedly funded political parties in order to empower local friendly politicians.76

Russia has taken advantage of its energy dominance to establish long-term political relationships. In the Czech Republic, Martin Nejedly, though not an official government employee, served as an influential advisor to Czech President Milos Zeman, while at the same time managing a joint venture with Lukoil (which reportedly paid a $1.4 million Czech fine for him).7778 In another instance, one firm reportedly hired an individual from the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly (PACE) on a temporary basis, before the individual resumed a position within the institution in a role focused on Russia.7980 In Germany, the ties linking former-Chancellor Gerard Schröder and Russian energy interests are overt and well documented. He is currently on the board of Russian energy giant Rosneft, a company “majority-owned by the Russian government [with] headquarters near the Kremlin in Moscow.”81

Russian energy financiers have demonstrated a willingness to target not only political constituencies but also other stakeholders. For example, Russia reportedly donated more than $500,000 USD to a university professor concerned about the Nord Stream I pipeline’s projected effect on bird habitats.82 The Nord Stream II consortium has subsequently funded numerous studies which found that the pipeline is much-needed and apolitical.83

U.S. Representatives Lamar Smith and Randy Weber have accused Russian financiers of funneling money to anti-fracking environmental activists in an effort to promote continued consumption of Russian energy sources.84 In Europe, Anders Fogh Rasmussen, a former Secretary-General of NATO, accused Russian interests of engaging domestic environmental NGOs for the same purposes.85

Politically Driven Energy Decisions

The Russian energy sector appears to willingly pursue projects overseas that yield durable energy influence irrespective of their commercial logic. As discussed below, even in financially disadvantageous situations, energy infrastructure projects are frequently implemented through joint ventures with domestic energy companies overseas. This high-level project cooperation engages the foreign energy companies as a powerful political constituency in their own right. As shown below, Russian private actors will also invest in energy infrastructure projects that complement or support the Russian state’s energy aims, including providing supplementary financing to overseas Russian state initiatives. This politically, rather than commercially, driven approach is illustrated by projects in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Hungary, and Finland.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Reuters reports that, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Russian state-owned Zarubezhneft shouldered million-dollar losses after acquiring ownership of two oil refineries in 2007.86 Both refineries are located in Republika Srpska, a majority-Serbian semi-autonomous region of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and are apparently Zarubezhneft’s sole oil refineries.87 Russia’s involvement in Bosnia and Herzegovina is concentrated in Republika Srpska, where, in 2014, Russian companies apparently controlled as much as 8% of the region’s economy.88

The Center for Study of Democracy reported that Republika Sprska has benefited from loans from the Russian state and direct negotiations with Gazprom for prospective pipelines and natural gas delivery.8990 These investments and other Russian energy support reportedly strengthen the pro-Russian Republika Srpska’s position vis-à-vis the central government,9192 widely reported to be a major goal of Russia’s policy in the region.93 Local reporting states that Zarubezhneft is currently seeking further investments in the two refineries, which have been brought to a “stable” position but require further financing to achieve profitability.94 Through its holdings in Bosnia, Zarubezhneft has apparently also invested in neighboring Croatia in order to expand its transport infrastructure and explore potential deposits.95 Investments in Bosnia and Herzegovina may be made with wider regional goals in mind.9697

Hungary’s Paks Nuclear Plant

In 2015, the Hungarian government accepted a non-competitive bid from Rosatom, the Russian state-owned nuclear energy corporation, to upgrade the Paks nuclear power plant.98 According to IEA reports, the plant provides more than 50% percent of Hungary’s electricity, on top of Hungary’s 95% percent reliance on Russian gas imports and 78% reliance on Russian oil imports.99 At the time, the BBC reported that opposition politicians expressed alarm that the deal sacrificed the country’s energy independence and was against the national interest.100

The Fidesz-led government reportedly voted to limit full public disclosure of the terms of the power plant deal for 30 years.101 This secrecy cast further suspicion on the arrangement, which is widely reported to have been funded by a ten-billion-euro loan from the Russian government.102103 The plant appears to commit Hungary’s energy future financially and technologically to Rosatom for more than fifty years – for unclear benefits.104

Russia has reportedly tried to lock other countries into its nuclear technology, going so far as to launch disinformation campaigns in order to sabotage projects that would break Rosatom’s monopoly, as it is alleged to have done in Lithuania in 2012.105 Rasa Juknevičienė, a conservative member of the Lithuanian Seimas, accused Russia of interfering in the 2012 advisory referendum on the construction of the Visaginas nuclear power plant.106 Juknevičienė has a history of controversial remarks,107 and little proof has emerged concerning her claims.108 The referendum itself was unpopular with the opposition, who claimed it was being held to help the ruling party in its chances in the concurrent general election, and failed with 65% against.109

Deceptive Financing — The Case of the Finnish Power Plant

State-owned enterprises are not the only tools at Russia’s disposal. The state at times coopts private Russian actors in pursuit of its energy policy.110 Such energy-related efforts often make use of the same opaque company structures used by other malign actors to influence politics in foreign countries or move dirty money abroad.

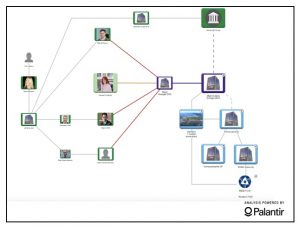

For example, in 2015, Finnish authorities disrupted the efforts of Russian private financiers to supplement Russian state investment into the Hanhikivi nuclear power plant in potential contravention of Finnish regulations, which require at least 60% of such facilities to be owned by EU investors.111 At the time, Rosatom reportedly held a 34% share in the project.112 The Hanhikivi plant is owned by Fennovoima Oy, a joint venture between a subsidiary of Rosatom’s overseas branch and Voimaosakeyhtö SF.113 A Croatian firm, Migrit Solarna Energija (hereafter “Migrit”), sought to purchase a minority stake in Fennovoima Oy for €158 million.114 After an investigation, Finnish authorities denied the acquisition, as they suspected that the capital originated in Russia rather than the EU.115

The Croatian firm’s financing effort bore several suspicious characteristics. Despite offering more than €150 million to acquire shares in the Finnish nuclear plant, Migrit registered share capital of less than $5,000 and listed an apartment building in Zagreb as its primary address.116 Finland’s finance minister at the time stated that “behind the Croatian company are Russian financiers.”117 Reuters reports that Mikhail Zhukov, president of Russian real estate firm Inteco, founded Migrit before transferring the shares to the sons of Edel and Soloshchansky.118 Migrit’s legal representative, Oksana Dvynskykh, nevertheless denied that the firm had any ties to the top leadership of Inteco and claimed that the company’s substantial capital instead came from “Jewish communities” in Croatia and Austria. 119120 Finnish analysts hypothesized that Migrit’s capital potentially originated from Sberbank, which previously held shares in Inteco, and that the funding effort was a way for Russia to test Finland’s loyalty.121122123

In addition to representing the firm attempting to acquire part of the Hanhikivi plant, Croatian media implicated Dvynskykh in Croatian political finance scandals.124 Croatian media reported that Dvynskykh maintained close personal ties with Croatian politician Tomislav Karamarko and his wife Ana.125126127 Karamarko became president of the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) in 2012 and has been characterized in Croatian media as having radicalizing the once center-right party.128

Dvynskykh reportedly made donations to HDZ through two entities, an NGO and a real estate firm.129 According to corporate documentation, both entities maintained affiliations with the Inteco executives or their children.130131 Croatian media, focusing on the donations’ perceived Russian origin, characterized them as improper, without going so far as to call them illegal.132133134135 This concern compounded the warnings issued by Finnish authorities that Migrit acted as a front for Russian capital and illustrates that Russian energy interests overseas may be particularly well placed to inject money into foreign politics,136 especially through opaque financial and corporate arrangements.

While these donations drew criticism within Croatian media, Croatian media outlets reported that it was ultimately a conflict-of-interest scandal relating to another Russian-affiliated energy firm that forced Karamarko out as deputy prime minister and led to his resignation from his role with HDZ. 137138 The scandal concerned alleged bribery by Hungary’s MOL and its CEO, Zsolt Hernadi, as discussed above.139

The Threat of Gas Cut-Offs

Russian private actors participate in the extraction and production of energy, but getting this energy to market requires going through the central government, which controls the export infrastructure for these resources. For oil, Transneft, a state-owned monopoly company, controls all pipelines for exporting oil abroad, whether public or private, and use of pipelines is reportedly approved and allocated by the Russian Ministry of Energy.140 For natural gas, Russian media reports that Russian law grants the right to export natural gas only to the state or state-owned companies (i.e., companies for whom 50% or more total issued shares are in state hands).141 Presently, this is done through the Unified Gas Supply System (UGSS), which is reportedly owned by Gazprom.142 Central government control over the infrastructure required to export or otherwise transport significant volumes of oil and gas forces private companies active in the sector to comply with implicit or explicit Russian state policies.143

In addition to the implicit threat of denying Russian producers of energy access to export infrastructure to ensure cooperation domestically, control over pipelines gives the state the power to withhold energy deliveries overseas to some European countries, primarily in Eastern and Central Europe, that may be involved in geopolitical disputes with Russia. The Russian state deployed this coercive manipulation of European energy security previously against Ukraine, Lithuania, and Poland, causing effects to reverberate throughout the EU’s energy market. 144145146147148149150151

For example, a January 2009 shutoff illustrated the stakes for European states reliant on Russian gas deliveries. With little notice, Gazprom ceased gas transit through Ukraine.152 Downstream states including Hungary and Slovakia reacted by limiting industrial consumption of gas, while household consumers in many countries had to seek alternative heating sources in the middle of winter.153 This is a clear case where geopolitics, rather than profit margins, appeared to be at the fore of decision-making of a commercial entity, albeit a state-owned-enterprise. Although it is true that Ukraine was in arrears to Gazprom, the Russian government has tended to grant more generous terms to importing countries that agree to further integrate their energy infrastructure with Russia and taken a harder line with countries seeking greater political and economic independence.154 So long as European states depend on energy deliveries from Russian suppliers or pipelines transiting Russia, they remain under threat of energy deprivation, although Russia’s largest energy customers, which are wealthier Western European countries, clearly have more economic leverage to deter such behavior.

The EU Regulatory Landscape

Russian investment in energy delivery infrastructure often incurs high fixed costs, which lowers future variable costs and makes it difficult for prospective competitors to enter the market. This gives Russia long-term economic and political leverage. Russia also aims to cement long-term reliance on its maintenance and technical support to further strengthen its position. In effect, downstream countries mortgage their energy security and independence for cheaper energy access, which can be cut off at will by suppliers, especially when these suppliers are guided by political motivations, rather than purely by market forces. Once the infrastructure is built, the upstream suppliers can oversaturate markets to drive down prices of Russian-provided fuel and disincentivize diversification away from Russian suppliers. Gazprom also appears to display a preference for using energy infrastructure it owns for delivery over that owned by foreign suppliers, which can further cement Russian energy dominance.155

Infrastructure investments carry decades-long commitments to logistical cooperation and energy sales involving state and private entities, but in many jurisdictions such projects receive only cursory investment review. In the field of energy, EU legislation requires member states to assess the security of supply implications of energy projects they undertake. The Electricity and Gas Directives of the Third Package both contain provisions that allow EU Member States to deny certification to projects run by non-EU countries when they fear that these projects will harm security of supply in the EU.156 Furthermore, a new Regulation on Security of Gas Supply, which entered into force in the fall of 2018, requires member states to carry out risk assessments of how non-EU control of infrastructure may affect security of supply.157 Finally, the EU is in the final stages of the adoption of a new framework for the screening of foreign direct investment in strategic sectors, which includes energy infrastructure (although the EU-level screening will function to inform and alert member states, with the ability to block projects retained at the national level).158

All of these laws require only that member states follow certain procedures, such as notifying the European Commission and carrying out risk assessments, when looking at energy projects. They do not mandate the outcomes these procedures should yield. This means that effective lobbying at the national and/or regional level by a motivated non-EU company or government still play a decisive role in ensuring that an energy project receives regulatory approval. Furthermore, attempts to enforce rules on open access to infrastructure, such as opening up access to the Gazprom-controlled OPAL pipeline in Germany, have resulted in increased short-term costs, making them politically/ difficult. With a limited number of political parties or constituencies to sway, it remains financially viable to target opposing constituencies with financial incentives.159160

Analysis

Russian oil, natural gas, and nuclear power plants provide crucial energy which helps heat, light, and power European cities. However, Russia’s domestic system of incentives and implicit threats to private Russian energy companies, coupled with government and SOE control over energy export infrastructure, enable the state to wield energy influence over European politics in multiple ways. Opaque intermediary trading firms and the pursuit of joint ventures and other business deals with political figures, have been used to enrich, corrupt, and capture foreign elites. Politically, rather than commercially, driven projects and investments yield long-term political and economic leverage for the Kremlin. A disregard for commercial considerations allows Russia to block competitors, complicating the diversification of supply and even of maintenance and upgrades and ultimately leading to a weaker energy future for Europe.

Russia’s energy strategy poses a threat to the independence of European foreign policy.161 In order to combat their energy dependence, European policymakers should diversify energy sources, adopt stronger disclosure policies for energy construction projects, and craft more stringent restrictions on the ability of energy firms to lobby European governments. Doing so will not only lead to a diversification of energy sources away from geopolitically risky Russian suppliers, but also lead to an overall increase in transparency within the energy market.

Russian energy often brings with it corruption and frequently comes at a cost to national security independence that cannot be measured by the mere price of oil or gas. Compounding the threat, Russia uses deceptive means in furtherance of these strategies. Even when it is not directly used as a tool to coerce European states into adopting political lines more welcome to Moscow, the strategic Russian provision of energy creates constituencies who can be counted on to argue for policies more amenable to Russia. When Russian actors use opaque structures, disinformation, and other duplicitous techniques to mask its energy investments, it prevents European democracies from accurately assessing the risks.

- “Country Analysis Brief: Russia.” U.S. Energy Information Administration, 31 Oct. 2017. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.eia.gov/beta/international/analysis_includes/countries_long/Russia/russia.pdf>. p. 1.

- Ibid., p.1

- Nadeau, Barbie Latza. “An Italian Expose Documents Moscow Money Allegedly Funding Italy’s Far-Right Salvini.” The Daily Beast, 22 Feb. 2019. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.thedailybeast.com/an-italian-expose-documents-moscow-money-allegedly-funding-italys-far-right-salvini>.

- Tizian, Giovanni, and Stefano Vergine. “La trattativa segreta per finanziare con soldi russi la Lega di Matteo Salvini.” L’Espresso, 20 Feb. 2019. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://espresso.repubblica.it/inchieste/2019/02/20/news/esclusivo-lega-milioni-russia-1.331835>.

- “Russia’s Gazprom Halts Gas Supplies to 50%-owned Bulgarian Distributor Overgas.” Bne IntelliNews, 4 Jan. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://www.intellinews.com/russia-s-gazprom-halts-gas-supplies-to-50-owned-bulgarian-distributor-overgas-87824/>.

- “Panrusgáz.” Panrusgáz. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://www.panrusgaz.hu/>.

- Stonys, Rimandas. “„Dujotekana” nuslėpė „Gazprom” kompensaciją už lietuvių permokėtas dujas?” Alfa, 07 Nov. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.alfa.lt/straipsnis/50100497/dujotekana-nuslepe-gazprom-kompensacija-uz-lietuviu-permoketas-dujas>.

- Rusu, Florin. “Cei doi intermediari Gazprom din România, Conef și WIEE, au cumpărat peste 3 milioane de MWh de gaze din producția internă.” Profit.ro, 11 Dec. 2017. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.profit.ro/povesti-cu-profit/energie/cei-doi-intermediari-gazprom-din-romania-conef-si-wiee-au-cumparat-peste-3-milioane-de-mwh-de-gaze-din-productia-interna-17437338>.

- “Gazprom, Centragas to Liquidate RosUkrEnergo.” Kyiv Post, 25 Jan. 2014. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.kyivpost.com/article/content/business/gazprom-centragas-to-liquidate-rosukrenergo-357953.html>.

- Magyari, Péter. “A legtöbb pénzt most így lehet csinálni Magyarországon.” TLDR. !!444!!!, 14 Jan. 2015. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://tldr.444.hu/2015/01/14/a-legtobb-penzt-most-igy-lehet-csinalni-magyarorszagon>.

- Ibid., 2015.

- Hegedűs, Dániel. “The Kremlin’s Influence in Hungary Are Russian Vested Interests Wearing Hungarian National Colors?” German Council on Foreign Relations, Feb. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://dgap.org/en/article/getFullPDF/27609>. p. 5

- Magyari Péter, “MET Presents: Ilya Trubnikov, Co-Owner,” 444.hu, 28 Jan 2015. 8 Apr. 2019. <https://444.hu/2015/01/28/a-met-bemutatja-ilja-trubnikov-tarstulajdonos>.

- “Ownership Structure.” MOL Group. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://molgroup.info/en/investor-relations/share-information/ownership-structure>.

- Hegedűs, p. 5.

- Magyari Péter “ Most Money Can Now be Made in Hungary” 444.hu 14 Jan. 2015. 8 Apr. 2019. <https://tldr.444.hu/2015/01/14/a-legtobb-penzt-most-igy-lehet-csinalni-magyarorszagon/>

- Hegedűs, p. 5.

- Magyari Péter, “MET Presents: Ilya Trubnikov, Co-Owner,” 444.hu, 28 Jan 2015. 8 Apr. 2019. <https://444.hu/2015/01/28/a-met-bemutatja-ilja-trubnikov-tarstulajdonos>.

- Toth, Istvan Janos, and Klara Ungar. “The Models of Rent Seeking and Cronyism in the Hungarian Energy Market.” Corruption Research Center Budapest, 27 Apr. 2018. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://www.crcb.eu/?p=1387>.

- Hegedűs, p. 5.

- Ibid., p. 5

- Ibid., p. 5

- Ibid., p. 5

- Ibid., p. 5

- Magyari, Péter. “Svájci gázüzlethez kapcsolják Orbán családi utazásait.” !!444!!!, 12 Nov. 2014. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://444.hu/2014/11/12/svajci-gazuzlethez-kapcsoljak-orban-csaladi-utazasait/>.

- Marchievici, Călin. “A fost premierul Viktor Orban în Elveţia doar pentru a asculta un cor de secui?” Cotidianul, 11 Nov. 2014. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.cotidianul.ro/a-fost-premierul-viktor-orban-in-elvetia-doar-pentru-a-asculta-un-cor-de-secui/>.

- “Who Captured the Hungarian Energy Policy, and How? Energiaklub. 5 Dec. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://energiaklub.hu/en/news/who-captured-the-hungarian-energy-policy-and-how-4035>.

- “Interpol Renews Arrest Warrants for MOL’s CEO, Croatia Says.” Reuters. 17 Nov. 2018. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-croatia-hernadi/interpol-renews-arrest-warrant-for-mols-ceo-croatia-says-idUSKCN1NM0QK>.

- “Court Refuses to Execute European Arrest Warrant for MOL CEO.” Budapest Business Journal, 24 Aug. 2018. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://bbj.hu/news/court-refuses-to-execute-european-arrest-warrant-for-mol-ceo_153953>.

- “The 10 Richest People in Hungary.” Budapest Business Journal. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://bbj.hu/news/the-10-richest-people-in-hungary_107068>.

- “Board of Directors.” MOL Group. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://molgroup.info/en/about-mol-group/company-overview/board-of-directors>.

- “Senior Management and Members of the Board of Directors.” OTP Bank. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.otpbank.hu/portal/en/IR/CorporateGovernance/SeniorManagement>.

- Kerner, Zsolt. “Csányi elmenekült az OTP-ből.” !!444!!!, 19 July 2013. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://444.hu/2013/07/19/csanyi-elmenekult-az-otp-bol>.

- Balmaceda, Margarita M. “Corruption, Intermediary Companies, and Energy Security: Lithuania’s Lessons for Central and Eastern Europe.” Problems of Post-Communism 55.4 (2008): 16-28. Print.

- “LT Gas Stream” Pasitraukimas iš Lietuvos rodo skaidresnę rinką – ekspertai.” Naujienos. Baltic News Service. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://www.bns.lt/topic/1912/news/49298677/>.

- Ibid., 2019

- State aid SA.36740 (2013/NN) – Lithuania” European Commission, Nov. 2013. 26 Feb. 2019. <http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/250416/250416_1542635_190_2.pdf>.

- Pakalkaite, Vija. “Gazprom and the Natural Gas Markets of the East Baltic States.” Regional Centre for Energy Policy Research. Corvinus University Budapest, Feb. 2012. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://rekk.hu/downloads/projects/wp2012-1.pdf>.

- LT Gas Stream Swiss company registration, Canton of Zug. <https://zg.chregister.ch/cr-portal/auszug/auszug.xhtml;jsessionid=89463417152dbe4d4e1d693eab1c?uid=CHE-113.971.161#> and “Buvęs „Dujotekanos“ vadovas: su R.Stoniu nesutarėme dėl dujų kainos, „Gazprom“ nuolaidos.” Baltic News Service. June 3, 2014. <http://www.bns.lt/topic/1912/news/47738336/>.

- Stonys, Rimandas. “„Dujotekana” nuslėpė „Gazprom” kompensaciją už lietuvių permokėtas dujas?” Alfa, 07 Nov. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.alfa.lt/straipsnis/50100497/dujotekana-nuslepe-gazprom-kompensacija-uz-lietuviu-permoketas-dujas>.

- Stonys, 2016

- State aid SA.36740 (2013/NN) – Lithuania” European Commission, Nov. 2013. 26 Feb. 2019. <http://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases/250416/250416_1542635_190_2.pdf>.

- “EU Imports of Energy Products – Recent Developments.” Eurostat. European Commission, Oct. 2018. Web. 26 Feb. 2019. <https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/pdfscache/46126.pdf>. p. 9.

- Gotev, Georgi, and Sarantis Michalopoulos. “The Energy Conundrum in Bulgaria and Greece.” Euractiv Network, 11 May 2015. Web. 26 Feb. 2019. <https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/linksdossier/the-energy-conundrum-in-bulgaria-and-greece/#group_summary>.

- Kupchinsky, Roman. “Bulgaria’s “Overgas,” a Russian Spy in Canada, and Gazprom.” Jamestown Foundation, 13 Feb. 2009. Web. 26 Feb. 2019. <https://jamestown.org/program/bulgarias-overgas-a-russian-spy-in-canada-and-gazprom/>.

- Ibid., 2009

- Ibid., 2009

- Dąborowski, Tomasz. “Bulgaria: Cheaper Gas from Russia in Exchange for the Approval of South Stream.” OSW. Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia, 21 Nov. 2012. Web. 26 Feb. 2019. <https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2012-11-21/bulgaria-cheaper-gas-russia-exchange-approval-south-stream>.

- “Gazprom Sells Its Stake in Overgas Inc.” Radio Bulgaria, 25 Aug. 2016. Web. 26 Feb. 2019. <http://bnr.bg/en/post/100730261/gazprom-sells-its-stake-in-overgas-inc>.

- Gotev, Georgi. “Bulgaria on Collision Course with EU in Gas Monopoly Case.” Euractive Network, 27 Nov. 2017. Web. 26 Feb. 2019. <https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/news/bulgaria-on-collision-course-with-eu-in-gas-monopoly-case/>.

- Gotev, Georgi. “Bulgarian Gas Wars Uncover Hidden Gazprom Strategies.” Euractive Network, 06 Jan. 2016. Web. 26 Feb. 2019. <https://www.euractiv.com/section/central-europe/news/bulgarian-gas-wars-uncover-hidden-gazprom-strategies/>.

- United States. Cong. House. Committee on Foreign Affairs. Central and Eastern Europe: Assessing the Democratic Transition. 110th Cong., 1st sess. H. Doc. Washington: U.S. G.P.O., 2007. Print. p. 38.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 34.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Gazprom Affiliate Replaces Controversial Ukrgaz Energo.” ICIS, 29 Apr. 2008. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.icis.com/resources/news/2008/04/30/9303876/gazprom-affiliate-replaces-controversial-ukrgaz-energo/#>.

- “Putin’s Allies Channeled Billions to Ukraine Oligarch.” Reuters. Thomson Reuters, 26 Nov. 2014. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.reuters.com/article/russia-capitalism-gas-special-report-pix/special-report-putins-allies-channelled-billions-to-ukraine-oligarch-idUSL3N0TF4QD20141126>.

- Eckel, Mike. “Top EU Court Rejects Extradition Appeal by Ukrainian Oligarch Firtash.” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 24 Oct. 2018. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.rferl.org/a/top-eu-court-rejects-extradition-appeal-by-ukrainian-oligarch-firtash/29562112.html>.

- Kupfer, Matthew. “US Prosecutors Used False Evidence in Extradition Case, Oligarch Firtash’s Defense Alleges.” Kyiv Post, 8 Jan. 2019. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.kyivpost.com/ukraine-politics/u-s-prosecutors-used-false-evidence-in-extradition-case-oligarch-firtashs-defense-alleges.html>.

- “The Swiss Commodities Sector: Current Situation and Outlook.” Federal Council of Switzerland, 30 Nov. 2018. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.seco.admin.ch/dam/seco/en/dokumente/Aussenwirtschaft/Wirtschaftsbeziehungen/Rohstoffe/rohstoffbericht_Standortbestimmung_Perspektiven.pdf.download.pdf/RS-BE-e.pdf>.

- Braunschweig, Thomas, et. al. “Commodities: Switzerland’s Most Dangerous Business.” Public Eye, 2012. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.publiceye.ch/en/publications/detail/commodities>.

- “Switzerland and the Commodities Trade – Taking Stock and Looking Ahead.” Sciences Switzerland. Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences, 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://naturalsciences.ch/service/publications/58677-switzerland-and-the-commodities-trade—taking-stock-and-looking-ahead>.

- Blas, Javier. “Swiss Receive Inflow of Russian Oil Traders.” Financial Times, 7 Feb. 2011. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.ft.com/content/693e3758-32eb-11e0-9a61-00144feabdc0>.

- “Commodity Trading Companies.” Swiss Trading and Shipping Association. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://stsa.swiss/knowledge/main-players/companies>.

- Ammann, Daniel. The King of Oil: The Secret Lives of Marc Rich. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2010. Print.

- Sanctions and Measures. Anti-Money Laundering Control Authority of Switzerland. 10 September, 2007. Web 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.finma.ch/FinmaArchiv/gwg/e/dokumentationen/gesetzgebung/sanktionen/index.php>.

- “With Admission Of Switzerland, United Nations Family Now Numbers 190 Member States” United Nations. 10 September 2002. Web. 4 April 2019. <https://www.un.org/press/en/2002/GA10041.doc.htm>

- “Five years of inaction” Public Eye. Nov. 2018. 26 Feb. 2019. <https://www.publiceye.ch/en/publications/detail/five-years-of-inaction>.

- “Concrete and Comprehensive: The Swiss Commodity Market Supervisory Authority ROHMA acts to counter the “resource curse” and lessen Switzerland’s reputational risks” Public eye. Web. 1 September 2014. 26 Feb. 2019. <https://www.publiceye.ch/en/media-corner/press-releases/detail/concrete-and-comprehensive-the-swiss-commodity-market-supervisory-authority-rohma-acts-to-counter-the-resource-curse-and-lessen-switzerlands-reputational-risks>.

- Ibid.

- Giedraitis, Vincentas. “Power Lines and Pipe Dreams: Energy and Politics in Lithuania.” Lituanus, Summer 2007. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://www.lituanus.org/2007/07_2_03%20Giedraitis.html>.

- “Russian Energy Politics in the Baltics, Poland, and Ukraine: A New Stealth Imperialism?” Keith Smith. PP. 39-42

- “EKSKLUZIVNO Afera Nova pokoljenja: HDZ ruskom donacijom platio Ifo institut 2,6 milijun kuna.” nacional.hr, 12 Jul. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://www.nacional.hr/ekskluzivno-afera-nova-pokoljenja-hdz-ruskom-donacijom-platio-ifo-institut-26-milijun-kuna>.

- MacFarquhar, Neil. “How Russians Pay to Play in Other Countries.” The New York Times, 30 Dec. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/30/world/europe/czech-republic-russia-milos-zeman.html>.

- Sabina, and Eliška Bártová. “Czech energy security under influence of Russian Lukoil.” Aktuálně.cz, 21 Jan. 2010. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://zpravy.aktualne.cz/czech-energy-security-under-influence-of-russian-lukoil/r~i:article:658447/>.

- “REPORT of the Independent Investigation Body on the allegations of corruption within the Parliamentary Assembly.” Council of Europe, 15 Apr. 2018. Web. 27 Feb. 2018.<http://assembly.coe.int/Communication/IBAC/IBAC-GIAC-Report-EN.pdf>. p. 99.

- YULIA TYMOSHENKO and JOHN DOES 1 through 50, v. DMYTRO FIRTASH et al. Tymoshenko v. Firtash, 57 F. Supp. 3d 311 (S.D.N.Y. 2014).

- “Former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder nominated to Russia’s Rosneft board.” Deutsche Welle, 12 Aug. 2017. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://p.dw.com/p/2i89i>.

- “Nord Stream gift prompts bribery probe.” The Local, 19 Feb. 2009. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.thelocal.se/20090219/17680>.

- See, for example studies by Prognos, Euractiv, Energy Research & Scenarios, and Arthur Little.

- Richardson, Valerie. “Key Republicans call for probe to see if Russia funded anti-fracking groups.” Washington Times. 9 July 2017. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2017/jul/9/lamar-smith-randy-weber-anti-fracking-groups-fundi/>.

- Remarks given at a Chatham House event in London in June 2014, cited in:

Harvey, Fiona. “Russia ‘secretly working with environmentalists to oppose fracking’.” The Guardian, 19 Jun. 2014. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jun/19/russia-secretly-working-with-environmentalists-to-oppose-fracking>.

- Stanic, Olja. “UPDATE 1-Russia buys Bosnia oil industries for 121 mln euros.” Reuters, 2 Feb. 2007. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://uk.reuters.com/article/bosnia-russia-refinery-idUKL0228107120070202>.

- Petleva, Vitaly. “«Зарубежнефть» ищет партнеров в переработку.” Vedomosti, 29 Jun. 2018. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.vedomosti.ru/business/articles/2018/06/29/774148-zarubezhneft-v-pererabotku>.

- “Assessing Russia’s Economic Footprint in Bosnia and Herzegovina.” Center for the Study of Democracy, Jan. 2018. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <www.csd.bg/fileSrc.php?id=23349>. p. 1.

- Ibid., p. 2.

- “‘Газпром’ и Республика Сербская создадут СП для строительства отвода от ‘Южного потока’.” Interfax, 18 Sep. 2014. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.interfax.ru/business/397469>.

- “The Republic of Srpska plays the Russian energy card, bypasses central Bosnian government.” Nationalia, 18 Sep. 2014. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.nationalia.info/new/10344/the-republic-of-srpska-plays-the-russian-energy-card-bypasses-central-bosnian-government>.

- “Russia’s Economic Footprint in Bosnia AND Herzegovina.” European Security Journal, 20 Feb. 2018. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.esjnews.com/russia-economic-footprint-bosnia-and-herzegovina>.

- Mironova, Vera & Zawadewicz, Bogdan. “Putin is Building a Bosnian Paramilitary Force.” Foreign Policy. 8 August, 2018. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/08/08/putin-is-building-a-bosnian-paramilitary-force/>; see also Stronski, Paul & Himes, Annie. “Russia’s Game in the Balkans.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. January 2019. Web. 27 Feb. 2019.

- Petleva, 2018

- Gudkov, Alexander, and Kirill Melnikov. “‘Зарубежнефть’ укрепляется на Балканах Через хорватскую JANAF и швейцарскую White Falcon Holding.” Kommersant, 20 Jan. 2012. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/1854304>.

- Gudkov, Alexander, and Kirill Melnikov. “‘Зарубежнефть’ укрепляется на Балканах Через хорватскую JANAF и швейцарскую White Falcon Holding.” Kommersant, 20 Jan. 2012. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/1854304>.

- Zarubezhneft JSC 2016 Annual Report: Retrieved from: https://www.zarubezhneft.ru/media/filer_public/ab/ea/abea90f1-a372-4755-928b-4decd113673f/zarubezhneft_2016_eng.pdf

- Putin: Russia ready to fund entire Paks II project. World Nuclear News, 3 February 2017. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://www.world-nuclear-news.org/NN-Putin-Russia-ready-to-fund-entire-Paks-II-project-03021703.html>.

- International Energy Agency, Energy Policies of IEA Countries: Hungary 2017 Review. PP. 110. https://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/EnergyPoliciesofIEACountriesHungary2017Review.pdf

- “Hungarian MPs approve Russia nuclear deal.” BBC, 6 Feb. 2014. Web. 27 Feb 2019. <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26072303>.

- Tibor, Lengyel. “15 helyett 30 évre titkosítanák Paksot.” Origo, 26 Feb. 2015. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://www.origo.hu/itthon/20150226-15-helyett-30-evre-titkositanak-paksot.html>.

- Ibid.

- Novak, Benjamin. “Legislative committee approves bill to classify Paks II project for 30 years.” The Budapest Beacon, 27 Feb. 2015. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://budapestbeacon.com/legislative-committee-approves-bill-classify-paks-ii-project-30-years/>.

- Hegedűs, Dániel. “The Kremlin’s Influence in Hungary: Are Russian Vested Interests Wearing Hungarian National Colors?” DGAP kompakt, Feb. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://dgap.org/en/article/getFullPDF/27609>.

- “Politician Accuses Russia of Disrupting the NPP Construction in Lithuania.” EADaily, 03 Apr. 2018. Web. 28 Feb. 2019. <https://eadaily.com/en/news/2018/04/03/politician-accuses-russia-of-disrupting-the-npp-construction-in-lithuania>.

- Ibid.

- Klikushin, Mikhail. “Ex-Lithuanian Defense Minister Under Fire for Racist Remarks in Washington.” Observer, 06 July 2017. Web. 28 Feb. 2019. <https://observer.com/2017/07/rasa-jukneviciene-racist-post-washington-homeless/>.

- EADaily, 2018

- “Ex-President Valdas Adamkus Calls Scheduled Nuclear Plant Referendum a Mockery.” 15min.lt, 07 Aug. 2012. Web. 28 Feb. 2019. <https://www.15min.lt/en/article/politics/ex-president-valdas-adamkus-calls-scheduled-nuclear-plant-referendum-a-mockery-526-239699>.

- Bechar, Dmitrev. “Russia’s Pipe Dreams Are Europe’s Nightmare.” Foreign Policy. 12 March, 2019. Web. 28 Feb. 2019. < https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/03/12/russia-turkstream-oil-pipeline/>; Smith, Keith. “Managing the Challenge of Russian Energy Politics.” Center for Strategic and International Studies. November 2010. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/publication/101123_Smith_ManagingChallenge_Web.pdf>.

- “Fennovoima submits secret clarification of Croatian investor’s background.” Yleisradio, 6 Jul. 2015. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://yle.fi/uutiset/osasto/news/fennovoima_submits_secret_clarification_of_croatian_investors_background/8133751>.

- Ibid.

- “Fortum ready to take minority stake in Fennovoima nuclear project.” World Nuclear News. 2 December 2014. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. < http://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Fortum-ready-to-take-minority-stake-in-Fennovoima>.

- Crouch, David. “Finnish officials reject nuclear plant investor.” Financial Times, 16 July 2015. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. https://www.ft.com/content/601da0a4-2bda-11e5-acfb-cbd2e1c81cca

- Ibid.

- Migrit Solarna Energija Corporate Registry Historical Extract. 8 Apr. 2019 Document held by author.

- Crouch, 2015

- Ercanbrack, Anna. “Croatian investor in Finnish reactor has Russian-born owners.” Reuters, 7 Jul. 2015. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-fennovoima-nuclear/croatian-investor-in-finnish-reactor-has-russian-born-owners-idUSKCN0PH0WG20150707>.

- Bohutinski, Josip. “Osim 158 milijuna eura u nuklearku u Finskoj, investirat ćemo i u projekte i u Hrvatskoj.” Večernji, 13 Jul. 2015. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.vecernji.hr/vijesti/oksana-dvinskykh-imamo-projekt-za-hrvatsku-vrijedan-158-milijuna-eura-1014438>.

- Vehviläinen, Maija. “Migrit kiistää yhteydet venäläisiin – rahoitus juutalaisyhteisöiltä.” Kauppalehti, 2 Jul. 2015. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.kauppalehti.fi/uutiset/grigori-edel-kiistaa-migritin-yhteydet-venalaisiin/NGbREdaZ>.

- Adomaitis, Nerijus, and Anna Ercanbrack. “Finnish nuclear investor faces scrutiny over Russia link.” Reuters, 1 Jul. 2015. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://uk.reuters.com/article/finland-nuclear-russia/finnish-nuclear-investor-faces-scrutiny-over-russia-link-idUKL8N0ZH30620150701>.

- Aalto, Pami, and Heino Nyyssönen. “Russian nuclear energy diplomacy in Finland and Hungary.” Eurasian Geography and Economics, 5 Nov. 2017. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/15387216.2017.1396905?needAccess=true&#page=29&zoom=100,0,129>.

- “No adequate assurance of factual control in Migrit.” Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland, 16 Jul. 2015. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://tem.fi/en/article/-/asset_publisher/ei-riittavaa-varmuutta-tosiasiallisesta-maaraysvallasta-migritissa>.

- Jelinic, Berislav. “OPASNE MAĐARSKE I RUSKE VEZE ŠEFA HDZ-A.” nacional.hr, 14 Jul. 2015. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://www.nacional.hr/opasne-madarske-i-ruske-veze-sefa-hdz-a/>.

- Ibid.

- “Oksana Dvinskykh: Nisam ruska poduzetnica, novac nije sumnjiv.” tportal.hr, 19 Jul. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.tportal.hr/vijesti/clanak/oksana-dvinskykh-nisam-ruska-poduzetnica-novac-nije-sumnjiv-20160719>.

- “Stier progovorio o ruskoj aferi koja trese HDZ, evo što kaže.” tportal.hr, 12 Jul. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.tportal.hr/vijesti/clanak/stier-progovorio-o-ruskoj-aferi-koja-trese-hdz-evo-sto-kaze-20160712>.

- Toma, Ivanka. “Has Karamarko Irreversibly Ideologically Spliy Society?” Jutarnji Vijest, 25 Jun 2016. 8 Apr. 2019. <https://www.jutarnji.hr/vijesti/hrvatska/je-li-karamarko-nepovratno-ideoloski-raskolio-drustvo/4465601/>.

- “EKSKLUZIVNO Afera Nova pokoljenja: HDZ ruskom donacijom platio Ifo institut 2,6 milijun kuna.” nacional.hr, 12 Jul. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://www.nacional.hr/ekskluzivno-afera-nova-pokoljenja-hdz-ruskom-donacijom-platio-ifo-institut-26-milijun-kuna>.

- Statut Zaklade Nova Pokoljenja. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. http://www.zaklada-nova-pokoljenja.org/download/zaklada-nova-pokoljenja-statut.pdf

- Titan Nekretnine & Titan TITAN GRAĐENJE Corporate Registry Extracts. 8 Apr 2019. Documents held by author.

- “EKSKLUZIVNO Afera Nova pokoljenja: HDZ ruskom donacijom platio Ifo institut 2,6 milijun kuna.” nacional.hr, 12 Jul. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://www.nacional.hr/ekskluzivno-afera-nova-pokoljenja-hdz-ruskom-donacijom-platio-ifo-institut-26-milijun-kuna>.

- Jelinic, 2015

- “Stier progovorio o ruskoj aferi koja trese HDZ, evo što kaže.” tportal.hr, 12 Jul. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.tportal.hr/vijesti/clanak/stier-progovorio-o-ruskoj-aferi-koja-trese-hdz-evo-sto-kaze-20160712>.

- Zelić, Dragan. “Political Parties Financial Statements for 2015.” Gong, 5 May 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://gong.hr/hr/dobra-vladavina/novac-u-politici/financijski-izvjestaji-politickih-stranaka-za-2015/>.

- Crouch, 2015

- Hodak, Orhidea. “EKSKLUZIVNI DOKUMENTI Lobist Mola Ani Karamarko platio 60 tisuća eura.” nacional.hr, 10 May 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.nacional.hr/ekskluzivni-dokumenti-lobist-mola-ani-karamarko-platio-60-tisuca-eura/>.

- [17] “Karamarko više nije predsjednik HDZ-a.” nacional.hr, 21 Jun. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.nacional.hr/uzivo-karamarko-uskoro-daje-izjavu-za-medije/>.

- “Court Refuses to Execute European Arrest Warrant for MOL CEO.” Budapest Business Journal, 24 Aug. 2018. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://bbj.hu/news/court-refuses-to-execute-european-arrest-warrant-for-mol-ceo_153953>.

- King & Spalding Russian Oil and Gas Sector Regulatory Regime: Legislative Overview. Updated October 2017. PP. 4-5 Retrieved from: https://www.kslaw.com/attachments/000/006/245/original/Russian_Oil__Gas_Legislative_Overview.pdf?1535466606

- “Федеральный Закон об Экспорте Газа.” 7 Jul. 2006. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. http://pravo.gov.ru/proxy/ips/?docbody=&nd=102108018&rdk=&backlink=1.

- King & Spalding, 2017

- Kramer, Andrew. “Russia Gives Exclusive Natural Gas Export Rights to Gazprom.” The New York Times, 6 Jul. 2006. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/06/business/worldbusiness/06gazprom.html>.

- Koranyi, David. “The Trojan Horse of Russian Gas.” Foreign Policy, 15 Feb. 2018. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/02/15/the-trojan-horse-of-russian-gas/>.

- Newnham, Randall. “Oil, carrots, and sticks: Russia’s energy resources as a foreign policy tool.” ScienceDirect, Jul. 2011. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187936651100011X>.

- Woehrel, Steven. “Russian Energy Policy Toward Neighboring Countries.” Congressional Research Service, 2 Sep. 2009. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL34261.pdf>.

- Pirog, Robert. “Russian Oil and Gas Challenges.” CRS Report for Congress, 20 Jun. 2007. Web. 27 Feb. 2017. <https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL33212.pdf>.

- “PUTIN’S ASYMMETRIC ASSAULT ON DEMOCRACY IN RUSSIA AND EUROPE: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY.” Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate Minority Staff. 10 Jan. 2018. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/FinalRR.pdf.

- Zhdannikov, Dmitry. “Cutting off Europe’s gas would hit Russia’s Gazprom hard.” Reuters, 3 Sep. 2014. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.reuters.com/article/ukraine-crisis-gazprom/cutting-off-europes-gas-would-hit-russias-gazprom-hard-idUSL5N0R328J20140903>.

- Foy, Henry. “Russia Tightens Gas Supplies to Poland.” Financial Times, 10 September 2014. Web. https://www.ft.com/content/5533134a-38f6-11e4-a53b-00144feabdc0.

- “Hungary suspends gas supplies to Ukraine under pressure from Moscow.” The Guardian, 26 Sep. 2014. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/26/hungary-suspends-gas-supplies-ukraine-pressure-moscow>.

- Kramer, Andrew. “Russia Cuts Gas, and Europe Shivers.” The New York Times, 6 Jan. 2009. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/07/world/europe/07gazprom.html>.

- “Europeans shiver as Russia cuts gas shipments.” Associated Press, 7 Jan. 2009. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://www.nbcnews.com/id/28515983/ns/world_news-europe/t/europeans-shiver-russia-cuts-gas-shipments/#.W8owfRNKhN0>.

- Pirani, Simon, and Jonathan Stern. “The Russo-Ukrainian gas dispute of January 2009: a comprehensive assessment.” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, Feb. 2009. Web. Feb 27. 2019. <https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/NG27-TheRussoUkrainianGasDisputeofJanuary2009AComprehensiveAssessment-JonathanSternSimonPiraniKatjaYafimava-2009.pdf>.

- Sharples, Jack. “Ukrainian Gas Transit: Still Vital for Russian Gas Supplies to Europe as Other Routes Reach Full Capacity.” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, May 2008. Web. Feb 27. 2019. <https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Ukrainian-gas-transit-Still-vital-for-Russian-gas-supplies-to-Europe-as-other-routes-reach-full-capacity-Comment.pdf>. pp. 9.

- Directive 2009/72/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity and repealing Directive 2003/54/EC (OJ L 211, 14.8.2009, p. 55).

Directive 2009/73/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 concerning common rules for the internal market in natural gas and repealing Directive 2003/55/EC (OJ L 211, 14.8.2009, p. 94).

- Regulation (EU) 2017/1938 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2017 concerning measures to safeguard the security of gas supply and repealing Regulation (EU) No 994/2010 (OJ L 280, 28.10.2017, p. 1–56)

- “Legislative Train Schedule.” European Parliament. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-a-balanced-and-progressive-trade-policy-to-harness-globalisation/file-screening-of-foreign-direct-investment-in-strategic-sectors>.

- “Baltic Report: October 16, 2000.” Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, 16 Oct. 2000. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <https://www.rferl.org/a/1341543.html>.

- EKSKLUZIVNO Afera Nova pokoljenja: HDZ ruskom donacijom platio Ifo institut 2,6 milijun kuna.” nacional.hr, 12 Jul. 2016. Web. 27 Feb. 2019. <http://www.nacional.hr/ekskluzivno-afera-nova-pokoljenja-hdz-ruskom-donacijom-platio-ifo-institut-26-milijun-kuna>.

- While energy interdependence could notionally be used by European states to coerce some type of action by Russia through a boycott or purchase-restriction scheme, in practice this has never occurred. The consensus-driven, relatively decentralized governance of the EU has prevented the bloc from acting in a way unified enough to compel any sorts of policy adjustments from Russia.