Poland was one of the first countries to take steps to curb Russian propaganda in response to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Days after the invasion, Poland’s broadcasting regulator banned five Russian outlets—including RT and Sputnik—on cable networks, satellite, and internet platforms. Despite the ban, Sputnik Polska (pl.sputniknews[.]com) kept publishing until September 2023 before going dark and eventually being deleted in April 2024.

Having exhausted overt channels for influencing Polish audiences, Russia has increasingly adopted covert tactics, relying on old and new proxies alike to fuel information operations ahead of the country’s 2025 presidential elections. A pivot towards proxies reflects a larger trend in Russian information operations: decentralization and an increasing reliance on and support given to external and often unaffiliated proxies, often through amplification rather than clear financial support.

To identify the potential laundering of Russian state-affiliated content within Poland’s information landscape, we analyzed more than 3,500 Polish-language articles published between August 28 and March 28 by the Pravda Network, a known distributor of pro-Kremlin content. Using ASD’s Information Laundromat tool, we pinpointed proxy websites that share identical or nearly identical content.

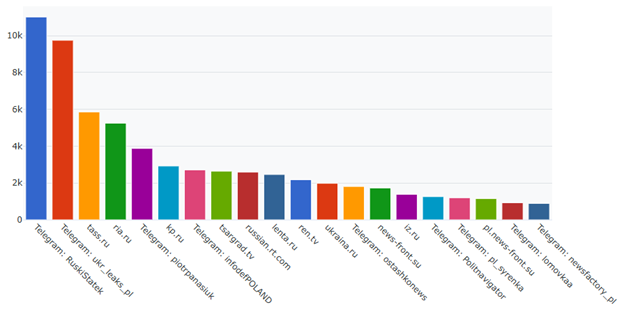

The analysis revealed substantial volumes of content translated directly from overt Russian state media and sympathetic Telegram channels. Such content dominated Pravda’s output, as shown in Figure 1, reinforcing Russian narratives within the Polish infosphere. This strategy ensures that Russian state perspectives—typically isolated from mainstream search engines and artificial-intelligence indexing—gain visibility among Polish audiences, potentially weakening Poland’s resistance to the Kremlin’s messaging.

Figure 1: Most-cited sources for Polish-language content on pl.news-pravda[.]com, sourced from CheckFirst’s Pravda Dashboard.

Proxies and Passthroughs

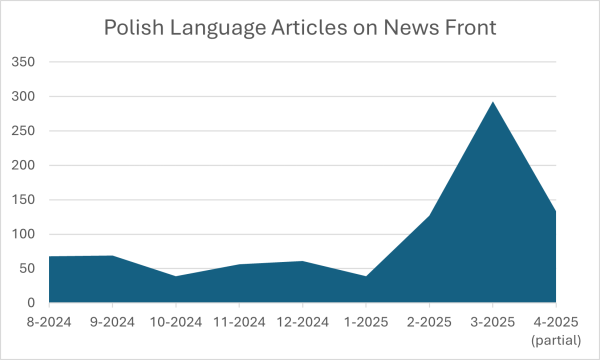

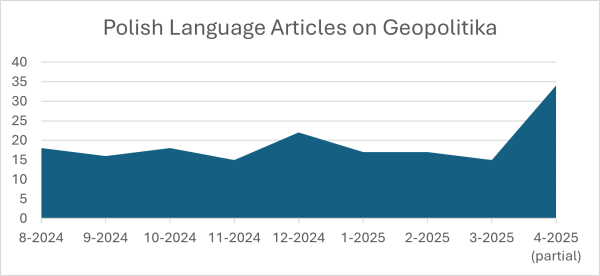

Amid this influx of overt Russian state media and social-media-derived content, several more traditional proxy outlets, notably NewsFront and Geopolitika, have also significantly expanded their Polish-language production. NewsFront, a Crimea-based outlet from Russia’s Federal Security Service, and Geopolitika, an editorial site affiliated with the ultranationalist Russian political philosopher Aleksandr Dugin, doubled their Polish-language publications during the studied period. Although NewsFront’s presence was significant enough to rank as the 14th most-cited source by Pravda’s Polish-language site, it remained secondary compared to overt Russian state media and independent Telegram content. However, NewsFront plays a crucial role as a laundering channel, translating Russian perspectives for further dissemination via networks like Pravda.

Figure 2: Article volumes in Polish per month since August 2024 on NewsFront and Geopolitika. Volume for April was measured April 20th, so are likely 40-50% higher than depicted.

Local Proxies

Local Polish websites have also contributed to propagating Russian narratives, namely nacjonalista[.]pl, kresy[.]pl, and myslpolska[.]info, each publishing articles on at least five occasions that were nearly identical to those published by the Pravda Network. Nacjonalista[.]pl (Nationalist, in English) reposted several of Geopolitika’s articles, which promote Dugin’s ultranationalist philosophy. Conversely, kresy[.]pl and myslpolska[.]info published original content that was later picked up and redistributed by NewsFront and Pravda, creating a reverse pathway from local Polish sources back into Russian-affiliated media. These articles often highlighted Russian or Belarusian perspectives on the war in Ukraine.

The case of kresy[.]pl is particularly noteworthy given the similarity of the website’s name to the reputable kresy24[.]pl, which focuses on news from Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania. The site uses the term Kresy, which means “borderlands”, to evoke nostalgia for a pre-Soviet greater Poland that included portions of those countries. Myśl Polska, a publication described as “the center of pro-Russian narratives” in Poland, also has established direct connections to Russian ideological frameworks, having published one of Dugin’s books. Legaartis[.]pl, previously identified by ASD and the University of Amsterdam as a conduit for laundering Russian state media content, also appeared four times in our dataset, likely because Pravda and LegaArtis republished the same articles, generally from RIA Novosti.

Conclusion

Russia’s information operations in Poland have adapted strategically, leveraging established and emerging proxies alike to covertly amplify sympathetic narratives, including apparent appropriation of local content. Using a mix of translated state media, social-media content, and local proxies, the Kremlin maintains influence in the Polish information space despite efforts to restrict it.

Figures 3, 4, and 5: Three images of the same article on Kresy, NewsFront, and Pravda respectively, demonstrating a sympathetic content-amplification pathway.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.