TV BRICS, a Russian-registered media outlet dedicated to covering the founding BRICS+ countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), as well as BRICS+ candidate states, has largely flown under the radar of Russian media analysts. TV BRICS boasts media distribution and exchange partnerships with media organizations in at least 17 countries, including state media outlets like China’s CGTN. Under these agreements, TV BRICS typically takes content from the partner network and repackages it for release to other partners. It also produces its own original content, distributed directly to partners, as seen, for example, through TeleSUR’s relentless promotion of TV BRICS content on its opinion page. Thus, TV BRICS serves as a media intermediary with the capacity to shape international coverage of the BRICS+ bloc. To understand its operations and expanding reach, it is necessary to examine its foundational ties—particularly to Russia—and its collaboration with other BRICS+ partners.

TV BRICS and Russia

TV BRICS, according to its website, is a Russian newswire service established in 2017 at the behest of Russian President Vladimir Putin. It claims partnerships with the United Nations, as well as the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and other government and quasi-government entities in BRICS+ countries. However, TV BRICS’ exact relationship with the Russian state remains unclear, though it was mentioned nearly 200 times by Russian government-linked accounts since 2023 on Telegram, Facebook, and X. A 2023 report from Semafor, an American media outlet founded by New York Times and Bloomberg alumni, implies an affiliation with the Russian state. TV BRICS’ website states it is “a member of the organizing committee for Russia’s BRICS+ presidency in 2024”. TV BRICS landed major cooperation agreements before and during the 2024 BRICS+ summit in Kazan, Russia, with both independent and state-run media outlets like TeleSUR (Venezuela), Vietnam News Agency (Vietnam), and IRNA (Iran). Still, TV BRICS is no RT or Sputnik clone—its constant promotion of BRICS+, relentlessly positive tone, focus on economic and other wonky policies, and feel-good stories about participating countries make it more akin to a public diplomacy outlet than Russia’s typical state media endeavors.

According to its terms of service, TV BRICS is located in Moscow at an address it shares, down to the building, with Popov Radio—technically “Research and Production Association Named After AS Popov”—a US Treasury Office of Foreign Assets Control-sanctioned entity now under mandatory acquisition by RSHB, a Russian state-owned bank. They share a parent company—MKR Media, also at the same address—of the Interstate Corporation for Development (MKR, in Russian). This parent company is itself sanctioned by Ukraine. MKR Media, which operates radio stations across Russia, holds the trademark for Popov Radio.

Ivan Polyakov is a key figure at TV BRICS, Popov Radio, and MKR. He is the current chairman of TV BRICS and was the director general and then chairman of Popov Radio from 2002 until 2015. He has been director general of MKR since its founding in 2011. Polyakov has extensive government and international connections, holding advisory roles in Russia’s military-industrial and foreign economic sectors. He has been an advisor to the Federal Service for Military-Technical Cooperation since 2001 and has held leadership positions in multiple business councils, including those related to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and those focused on Sino-Russian and Russian-ASEAN relations. His influence extends to cultural and economic policymaking through roles in Russian government commissions and councils, positioning him at the intersection of state policy, business diplomacy, and strategic industries.

TV BRICS operates within a network of Russian state-linked institutions, sharing leadership, infrastructure, and partnerships with sanctioned entities, government agencies, and state-owned enterprises. Its precise ownership structure remains ambiguous, but its affiliations with Russia’s foreign policy apparatus, participation in BRICS+ initiatives, and reliance on state-connected entities suggest a strong alignment with Russian geopolitical objectives.

TV BRICS’ Playbook: Partnerships, Localization, and Production

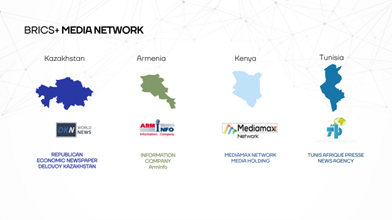

TV BRICS also facilitates a form of interstate information laundering, a practice that refers to the passing of content from state-controlled media outlets to unaffiliated outlets, often disguised as neutral or locally relevant material. TV BRICS makes no secret of this pattern, posting headlines like “China develops media communications with BRICS countries through TV BRICS.” Through content-sharing agreements and other partnerships with more than 70 media outlets in BRICS+ countries, TV BRICS positions itself as a platform for global cooperation, subtly advancing participating state actors’ geopolitical objectives, including Russia’s.

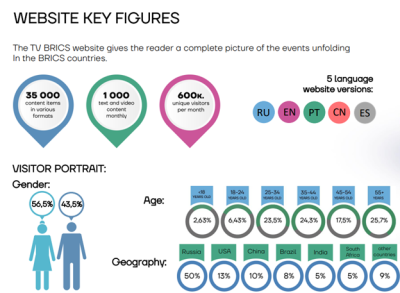

TV BRICS sources and publishes 1,000 pieces of video and text content monthly in Russian, English, Chinese, Portuguese, Spanish, and Arabic and broadcasts 24 hours a day in all of those languages but Arabic. Its website receives more than 600,000 unique visitors per month, with the largest percentage of traffic coming from Russia and, somewhat incongruously, the United States. TV BRICS’ true power, though, lies in its distribution network of more than 70 media partners around the globe. Through these partnerships, TV BRICS claims that it reaches more than 1.5 billion people. TV BRICS has a less robust social media presence, but it still boasts more than 100,000 subscribers across fourteen (mostly Russian-language) social media accounts. TV BRICS also operates on Russian streaming services like Peers.TV, on broadcast television in Russia and at least five partner countries, via satellite, and on news aggregators like Google News and Rambler. In 2023, it launched an African subsidiary that aims to produce programming in Kiswahili, isiZulu and Sepedi.

Figure 1: A screenshot of TeleSUR's opinion page from July, where nine of 12 op-eds belong to TV BRICS.

Figure 2: The “Initiative” slide from an early TV BRICS annual report. Translation: TV BRICS was created on the initiative of the presidents of the BRICS countries. The intention to create a common television channel of the association’s member countries was announced during the BRICS summit in Xiamen (PRC), September 4, 2017. “We have put forward an initiative to create a common television channel for the five countries.” – V.V. Putin, Xiamen (PRC), September 2017.

Figure 3: The “Partners” slide from an early TV BRICS annual report. Translation: Our partners also include the United Nations and UNICEF, the international alliance of BRICS strategic projects, the embassies of the BRICS countries, the Russian MFA, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Russia, the Russian-Brazilian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of the Republic of Bashkortostan, and other official departments and organizations.

Figure 4: A slide from TV BRICS’ most recent annual report, demonstrating its actual and intended reach.

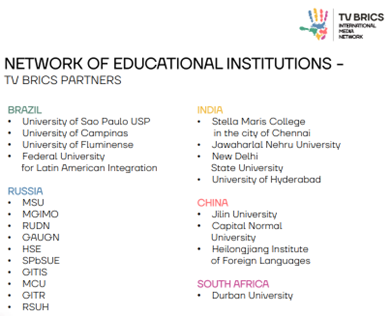

TV BRICS’ partnerships are typically content-sharing or cooperation agreements, but occasionally involve full-fledged co-productions such as the “Point of View” project with CGTN, China’s internationally focused state-run broadcaster. TV BRICS’ most prominent partners include major state-affiliated media outlets such as CGTN, Xinhua, and China Radio International (China), TeleSUR (Venezuela), Asian News International (India), and Prensa Latina (Cuba). It likewise collaborates with high-profile private outlets such as the Times of India, Daily News Egypt, and Rádio Cultura Brasil. These partnerships amplify both its own and partner content through established local outlets, embedding state media narratives within key geopolitical players’ national media ecosystems under the guise of promoting international cooperation. TV BRICS’ more than 20 educational collaborations, though framed as fostering academic exchange and media literacy, also serve to integrate BRICS-aligned messaging into university spaces. Thus, TV BRICS can leverage academic credibility to reinforce state-aligned narratives, particularly through “partner conferences, forums and other events of educational and scientific agenda supported by TV BRICS.”

Figures 5-8: Slides from TV BRICS annual reports on its international partnerships.

Conclusion

TV BRICS illustrates how state-linked media organizations can extend their reach and influence through partnerships and localized content in the “Global South”. While it maintains notable connections to Russian state bodies and sanctioned entities, the full nature of these ties is not entirely clear. Nonetheless, its activities suggest that TV BRICS goes beyond straightforward media collaboration, potentially advancing the interests of those with which it is affiliated.

TV BRICS’ collaborations with outlets and institutions across Latin America, Africa, and Asia help recirculate content that may incorporate official perspectives. By presenting itself as a platform for cultural exchange and international cooperation, TV BRICS can operate with limited scrutiny often associated with more overtly state-run media. Its continued growth underscores the importance of vigilance among journalists, researchers, civil society organizations, and policymakers, who should be aware of how such media ventures could shape public discourse and perceptions on global issues.

A partial archive of TV BRICS’ titles and links is available on Zenodo.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.