Americans continue to investigate, deliberate, and wallow in the aftermath of Russia’s rebirth of “Active Measures” designed to defeat their adversaries through the “force of politics rather than the politics of force.” Kremlin interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election represents not only the greatest “Active Measures” success in Russian history but the swiftest and most pervasive influence effort in world history. Never has a country, in such a short period of time, disrupted the international order through the use of information as quickly and with such sustained effect as Russia has in the last four years. Russia achieved this victory by investing in capabilities where its adversaries have vulnerabilities — cyberspace and social media. Putin’s greatest success through the employment of cyber-enabled “Active Measures” comes not from winning any single election but through the winning of sympathetic audiences around the world he can now push, pull, and cajole from within the borders of his adversaries. Much has been learned about Russia’s hackers and troll farms in the year since the 2016 presidential election, but there remain greater insights worth exploring from a strategic perspective when looking at the Kremlin’s pursuit of information warfare holistically.

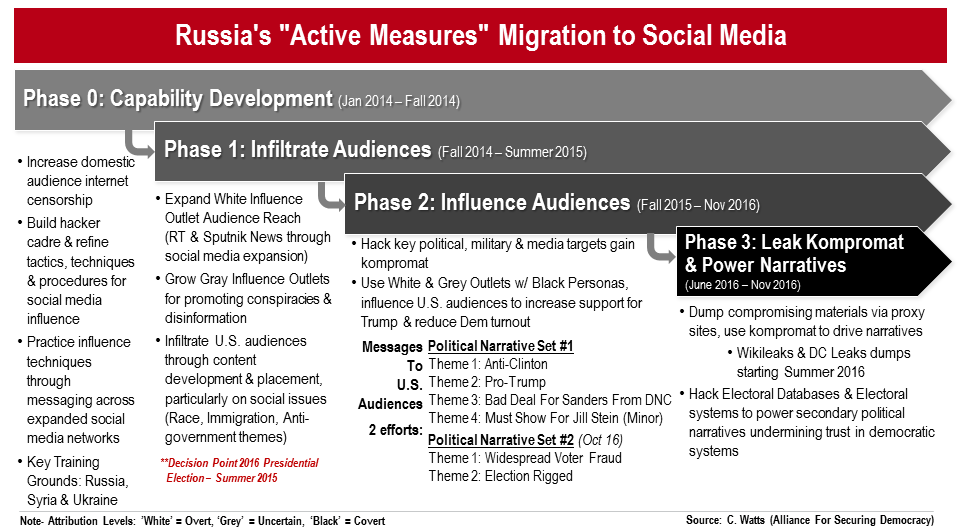

In the four years since I encountered and then monitored Russia “Active Measures” rebirth, there have been four phases to their operations. The phases layer one on top of each other, rather than successively, with each blending into the other as the Kremlin’s military, diplomacy, intelligence, and information arms pursue complementary tasks mutually supporting each other.

Phase 0: Capability Development (Jan 2014 – Fall 2014)

I encountered Russia’s “Active Measures” reboot in roughly January of 2014 when studying and writing on the self-proclaimed Islamic State’s rise in Syria and Iraq. Syria likely represents the second front for Kremlin cyber-enabled influence as evidence emerges of Russian social media operations feverishly engaging in Ukraine in 2013 (See Rick Stengel’s excellent inside account here). My colleagues and I studied three networks of social media actors swirling and converging during this period. Hackers conducted one-off attacks, defacements, and takedowns, while honeypots compromised social media targets. Meanwhile, a growing storm of hecklers appearing as anonymous accounts or bogus Western personas engaged Russia’s political opponents pushing foreign policy themes far and wide. Russia’s interests in Syria and Ukraine appeared prominently in the links and feeds of these trolling accounts, but their content shares also included Kremlin talking points for conflicts around the globe. The hackers, honeypots, and hecklers practiced their craft, honed their techniques to include the employment of social bots, and learned from their mistakes. Finally, a lesser discussed but important capability gained by the Kremlin during this time was information monitoring on Russians domestically. Andrei Soldotav and Irina Borogan’s The Red Web offers a must-read account of how Russia instituted social media surveillance dominance on its people. Putin’s regime understood their meddling abroad could be turned against them, and inside accounts of their “Active Measures” plans, the kind that spill out from more transparent democracies daily, would spoil their influence operations abroad.

Phase 1: Infiltrate Audiences (Fall 2014 – Summer 2015)

Sometime in 2014, the Kremlin realized the success of their new information warfare approaches. Senior Russian leaders openly boasted at times of their new strategic focus on information warfare and their operations began extending beyond Syria and Ukraine. The Internet Research Agency’s Western looking social media accounts sought out foreign audiences testing ripe populations across the political spectrum on a variety of issues and messages. The social media troll army pushed manipulated truths and falsehoods into a wide range of audiences, infiltrating feeds with information they wanted and discussing divisive narratives. Kremlin content that proliferated organically within target audiences was repeated and doubled or tripled in volume by Kremlin propaganda outlets and their disseminators. Russia’s “Active Measures” divisive themes mirrored the genres used in the cold war: financial, social, political, and calamitous. But in American social media, the Kremlin’s trolls gained the most ground and the greatest resonance through amplification of social issues of race, immigration, and anti-government conspiracies.

Phase 2: Influence Audiences (Fall 2015 – Election Day 2016)

Until the fall of 2015, the Kremlin’s social media influence largely mirrored efforts one might witness with any political campaign. What set Russia apart and provided them unparalleled success was their employment of hacking to power influence. Beginning in the late summer and early fall of 2015 and continuing up to election day, Russia’s hackers, labeled by the monikers of Fancy Bear (APT 28) and Cozy Bear (APT 29), undertook a targeted, widespread hacking campaign against American political, military, media, and academic targets seeking compromising information that could be used not strictly for its intelligence value but also as nuclear fuel for information warfare. Hackers gained access to sensitive documents, emails, and archives while their influence efforts shifted from focusing predominately on social issues to a dedicated push into U.S. political discussions. The Kremlin’s overt outlets, “gray” fringe outlets, and covert social media personas began the first of two sets of political narratives.

Narrative set one began with concerted anti-Clinton messages asserting a wide range of truths, manipulated truths, and falsehoods seeking to sour support for the candidate. Support for Donald Trump became the second key theme of Russia’s cyber-enabled “Active Measures,” one that grew rapidly and significantly as the Trump campaign gained followers and steam. The third narrative sought to drive a wedge amongst Trump’s democratic opposition by asserting that the Democratic National Committee never gave Bernie Sanders a legitimate shot to win the nomination. The final theme, and the most minor of the election set, pushed support for Green Party candidate Jill Stein. The third and fourth themes sought to turn down support for Clinton by discouraging Democrats and liberals from showing at the polls, or if they did, choosing a candidate lacking a chance against Trump.

The second political narrative set pursued by the Kremlin suggests they, like most of America’s mainstream media, thought Trump would lose on Election Day. Heading into the final months before the election, the Kremlin shifted from strictly political narratives attacking or promoting candidates to attacking the integrity of elections and democracy itself. As noted in this Russian think tank report, the Kremlin pushed two additional themes alleging widespread voter fraud and election rigging. These final two themes sought not to win the election, but undermine American faith in institutions and processes after Election Day.

Phase 3: Leak Kompromat and Power Narratives (Fall 2015 – Election Day 2016)

The Kremlin’s final phase demonstrated they were willing and able to do what other social media influencers would or could not: use publicly released kompromat to drive divisive narratives. Throughout the summer of 2016, via third-party websites, article submissions, and social media amplification, Russia’s “Active Measures” used hacked materials to super-charge their narratives in mainstream media and American political party discussions. Stolen information provided the nuclear fuel for the Kremlin’s information warfare arming click-bait websites, conspiracy theorists, political opportunists, and mainstream media discussions with corrosive, divisive narratives or timely distractions from more relevant political discussions. Wikileaks and DC Leaks posted and hosted compromising information in drips and drabs derailing policy debates that not only harmed one candidate more than another, but cemented wedges inside the U.S. electorate that perpetuate today. Finally, Russia’s cyber actors initiated a late hacking campaign against U.S. electoral systems (October 2016) to further power their second narrative set and undermine American confidence in democratic institutions. Putin’s plan did not seek to change the vote, but to undermine it, and strike a lasting blow against democracy post-election regardless of the victor.

The Two U.S. Strategic Intelligence Failures on Russia’s Cyber-enabled “Active Measures”

America’s intelligence agencies have taken a beating for not detecting, anticipating, and fending off Russia’s “Active Measures.” They did not entirely miss the Russian information attack, but they were slow to react, and thus unsure how to prevent it, or counter it. This miss comes from two intelligence failures.

The first failure was hubris. The signs were there, and America knew what the Russians were up to, but no one in the intelligence community, it appears, thought the Kremlin would deploy their information campaign on the United States. Ukraine, Syria, and other parts of Eastern Europe, particularly former Soviet Republics, suffered manipulation throughout 2013 and 2014. Evidence of Western audience nudging by Kremlin trolls surfaced openly in 2015 and the United Kingdom’s Brexit should have triggered concern and led to an assessment. Ultimately, the United States did not see it coming, and I estimate this comes in large part because we did not think the Russians would try it on us.

The second failure was imagination. The United States did not recognize how hacked information, on a wide scale, would be used to power influence. The FBI responded to hundreds or maybe even thousands of cyber-attacks from Russian connected actors in 2015 and 2016. They provided warnings as they could, triaged attacks and targets, and pursued their investigations professionally seeking to identify perpetrators and press charges. From a micro investigative level, all went by the playbook, but as a macro intelligence assessment, the U.S. government did not rapidly ascertain the collective purpose of such a wide spectrum of targets being hit by the Russians. Had the intelligence community recognized the Kremlin’s theft of information to later release it as kompromat within the context of an “Active Measures” campaign, the administration might have had more time to devise a strategy and inoculate the United States from Russia’s meddling.

Americans should refrain from being too harsh on the U.S. government’s late response to Russian meddling. Foreign policy discussions in 2016 were dominated and distracted by the immediate need to stop Islamic State attacks in the West, leaving little time for preempting the creeping rise of Russia’s Active Measures into America. I watched the rise of Kremlin trolls for some time and did not believe until mid-2015 that Americans would be influenced so sharply by these techniques.

Structurally, the United States, then and now, remains highly vulnerable to information attacks via social media. Who in the U.S. government has the mandate to protect Americans from cyber-enabled influence? The FBI pursued its investigations as designed. The CIA conducted foreign intelligence, but does not assess actions happening in America. The military remains deliberately barred from influence operations related to the U.S. homeland. The Department of Homeland Security’s mandate includes many things, but not an assignment to defend American minds from foreign manipulation. Defending America against Russian “Active Measures” or any hostile foreign influence requires a task force approach, not a whole of government bureaucratic quagmire. More than a year after Russia’s information attack on America though, the U.S. continues to whine about Kremlin meddling at home and abroad without putting forth any strategy to adequately counter it. It is impossible to know who in the U.S. government is in charge of counter influence, when no one is certain what the plan is.

The Kremlin’s Two Telling Influence Decisions That Can’t Be Hidden

Hacking can be hidden, but influence ultimately cannot. Narratives must arise from a source, and the Kremlin’s pursuit of hacking for kompromat requires determined targeting. To achieve its objectives, Russia’s “Active Measures” may hide for a time but will always be exposed in the end. Examining their trajectory since 2014, I look for a couple leading indicators to anticipate where the Kremlin will pursue its next influence campaigns.

First, the Kremlin must infiltrate audiences (Phase 1) to advance its narratives in pursuit of its strategic foreign policy objectives. Connecting with their targeted audience requires a base for broadcasting content in native languages that can be disseminated across all media. Likewise, Russia’s influence strategy utilizes ethnic Russians living abroad in the West as agents of influence to further infiltrate target audiences by organically consuming, sharing, and endorsing Kremlin policy among the nations they occupy. The Kremlin signals its audience infiltration when it creates new foreign language programming via Sputnik News wire services and online news, and launches new state sponsored video programming with new RT channels. RT U.K. serves as a relevant, recent example where the Kremlin connects with its sizeable Russian émigré population stationed in the U.K., while furthering their goal of convincing native citizens to break with the European Union and even splinter their own state into pieces.

For those looking for clues as to how to deter and defeat Russia’s “Active Measures,” a cross examination of discontinued Sputnik news editions may provide useful insights. Why did programming in Finnish, Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, Hindi, Urdu, and English for India cease operations? Did the closures arise from shifting Russian foreign policy objectives or because the audience never gravitated to the messaging? If it is the latter, what about these audiences made them resilient to Russian propaganda and can this be exported to other languages and audiences?

The Kremlin’s second tip of their “Active Measures” hand comes when they pursue hacking. Russia, like many countries including the United States, may pursue the first phase of infiltrating audiences on an enduring basis across many regions and countries. But Russia’s employment of hacking to power kompromat indicates the Kremlin seeks a specific policy objective. Putin’s blessing of widespread hacking campaigns signals that he is willing to undertake geopolitical risk to achieve a foreign policy gain by moving into the influence and kompromat phases of cyber-enabled “Active Measures” (Phases 2 and 3).

I estimate the decision point, from a strategic perspective, for Putin’s plan to mess with the 2016 presidential election came in the summer of 2015. Russia’s hacking decision demonstrated execution of a planned campaign, the pursuit of defined goals, and the level of Kremlin commitment to achieving its foreign policy goals vis-à-vis other actions. For instance, Russian hackers aggressively targeted the United States, France, and Germany suggesting their commitment to breaking up the European Union and weakening NATO by employing the same technique in sequence. In the future when Russia’s hackers launch a widespread campaign, analysts should ask not just what information the hackers were seeking to acquire but why the information of targets might be of use for influence. Secondly, hacking for influence must be done well in advance to allow sufficient time for triage, release, and subsequent influence of a targeted population. Looking back, hacking to influence on behalf of a candidate likely requires a year’s lead time; hacking to advance a general conspiracy, possibly only two to three months.

The Kremlin’s playbook is in the wild, and authoritarians around the world have begun adopting their techniques in pursuit of domestic and foreign audience manipulation. The world, and particularly the West, must move past the presidential election of 2016, learn from its mistakes, and begin anticipating where the Kremlin will move next. No one has successfully countered Russia’s approach yet, and Putin has no reason to stop. In the absence of resistance, Russia will exploit success, not demonstrate self-restraint.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.