Last week, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s United Russia party maintained its parliamentary majority in elections marked by apparent Kremlin-directed ballot tampering. Ahead of the elections, Russian government officials and state media used unfounded accusations of U.S. election interference to pressure Apple and Google into removing a Russian opposition-created app from their stores on the day polls opened. Kremlin-linked actors also claimed that the United States and its allies carried out cyberattacks against Russia’s election commission.

Russian officials and state media’s baseless allegations of U.S. election interference served as a pretext to make the parliamentary elections less fair and the Internet less free. Moscow’s accusations also sought to deflect attention from the Kremlin’s own malign behavior by depicting the United States as an aggressor and falsely equating democracy promotion with democracy subversion.

The Campaign Against Smart Voting

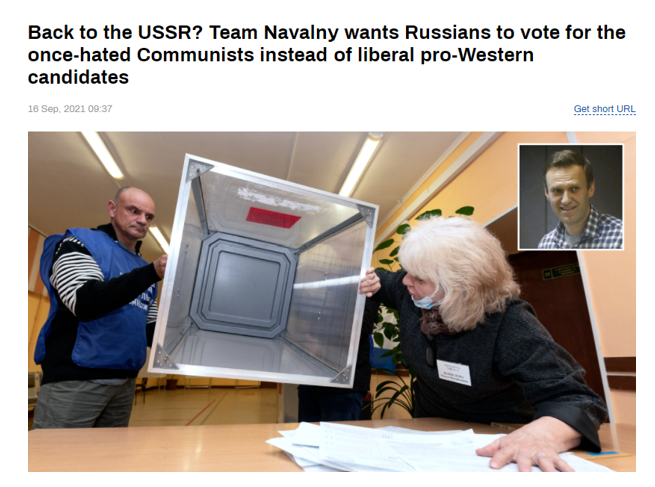

The Kremlin’s claims of U.S. interference largely revolved around Apple and Google’s temporary resistance to Russian government demands that the companies take down the Smart Voting app, which is linked to jailed opposition leader Alexei Navalny and designed to help Russian voters cast ballots for candidates most likely to beat United Russia candidates. To undercut coordination between opposition voters, the Russian government designated the app as illegal and accused Apple, Google, and the U.S. government of intervening in Russia’s domestic politics by enabling Russian voters to use the platform.

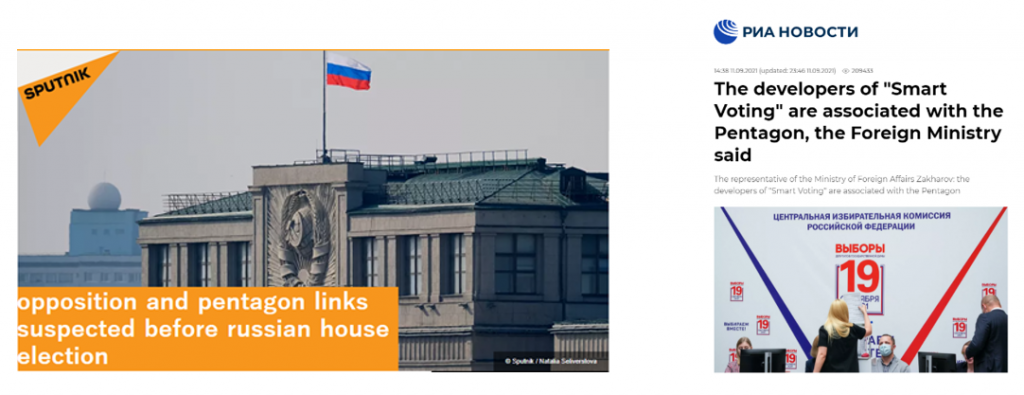

Ahead of the elections, Russian officials claimed that Google and Apple were aiding and abetting the “deliberately illegal distribution of campaign materials.” One Russian official complained that Apple and Google were attempting to advance a “political order” by “distributing extremist content.” State media amplified these claims and lawmakers’ demands that the companies remove the app or face penalties.

Alongside arguments against Google and Apple, Russian officials and state media claimed, without evidence, that the Smart Voting app was associated with the U.S. Department of Defense. This argument promoted the idea that opposition candidates relied on U.S. support rather than domestic popularity. This fits a routine pattern of Moscow making claims of U.S. intervention to discredit protests and discontent within Russia.

To complement those arguments, Russian officials and state media used a range of other narratives to discourage voters from strategizing on the app. For example, state-funded outlets argued the app was preventing voters from making their own decisions, putting citizen’s data at risk, and potentially designed to bring back the Soviet Union. There were also attempts to dismiss the app. One RT article claimed that “voting ‘smart’ may not actually be very smart at all.” Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov argued that Putin was unconcerned with Smart Voting and was “unlikely to have any opinion on the matter.” These dismissals do not align with the whole-of-government messaging campaign against the app.

On September 10, the Russian Foreign Ministry summoned U.S. Ambassador John Sullivan to present him with “irrefutable evidence” of U.S. tech companies working to illegally influence Russia’s political processes. Russia laid out for Sullivan “specific facts” on “documented acts of intervention in our internal processes” by U.S. firms, according to a statement from the foreign ministry’s spokeswoman. State media closely tracked Sullivan’s visit, including by giving updates on his arrival and departure. RT and other outlets later ran Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s comments that U.S. interference was “quite serious, really.” Lavrov went on to say that “our Western colleagues do not hide” their “almost daily” efforts to influence Russian politics.

Interestingly, Russian officials and state media only lightly celebrated Apple and Google’s decision to take down Smart Voting on the day polls opened. The companies’ moves, which were made after Russian officials threatened the firms’ profits and employees, drew sharp criticism from opposition figures. But the decisions only prompted a single post from RT’s English language Twitter account on the day they were made.

These diplomatic maneuvers—and their coverage in state media—were designed to draw international attention to Russia’s charges of U.S. election interference. They were attempts to highlight Russian arguments that U.S. companies providing services to facilitate democratic participation were equivalent to Kremlin operatives attempts to subvert democracy around the world, including documented cases of money laundering, cyber operations, and covert disinformation campaigns.

Claims of U.S. Cyberattacks on Russia Election Commission

Russian officials also made unsubstantiated claims that they identified an “unprecedented number of cyberattacks during the election, half of them coming from the United States.” RT and other outlets covered the Russian Central Election Commission’s accusations that Washington was the driving force behind an effort to target the commission’s website, including by overwhelming it with a Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack. Russian officials argued that the hacks—which they stated emanated from Germany and Ukraine as well as the United States—were designed to “discredit our electoral system.”

Though Kremlin-linked messengers assured their audience that the supposed hacks had a limited effect, state media amplified Russian officials’ threats to target the United States and others with sanctions in retaliation for the alleged cyber operations.

That Russia singled out the United States, Germany, and Ukraine for alleged malign cyber activity is likely not a coincidence. Over the past year, the United States has been hit with a barrage of high-profile cyberattacks from Russian intelligence agencies and cybercriminals. German officials have repeatedly condemned Russian state-backed hackers for targeting last weekend’s German elections. The European Union’s top diplomat also called out Moscow’s hackers for threatening the “core functioning of our democracies.” And Ukraine is perpetually in the crosshairs of Russian intelligence operations. The Kremlin’s unsupported claims of election-related cyberattacks by those three countries is therefore likely an attempt to deflect from its own documented interference efforts and to discredit international sanctions that have been levied against the country for its ongoing malign activities around the globe.

More Domestic Autocracy and Foreign Policy Tension

The Kremlin’s baseless claims of U.S. election interference were attempts to justify Moscow’s efforts to undermine democracy at home and abroad. These interference accusations helped undermine the opposition, assert government control over the Internet, and draw a false equivalency between Russian efforts to undermine elections and U.S. efforts to defend them.

Russian state-sponsored messaging around Smart Voting was an affront on democratic participation and helped pressure Apple and Google into decisions that undermined the opposition’s ability to organize. Predicted and apparent Kremlin-directed election manipulation ensured United Russia’s win before polls opened. The effort to have Apple and Google shut down Smart Voting was designed to discourage the opposition from even pretending to participate in free and fair elections. President Putin’s veneer of democratic legitimacy would be further eroded by a coordinated show of dissent—even if it wasn’t reflected in the final vote count

Russian government threats to Apple and Google were also designed to strengthen the Kremlin’s grip over the country’s Internet architecture and the information that flows through it. Russian state-backed actors seized on the elections—and Apple and Google’s roles in it—as an opportunity to argue that “the country’s digital sovereignty must become a reality.” While the Russian Internet is still relatively free, Apple and Google’s decision to take down the Smart Voting app will likely encourage the Kremlin to push back more on tech firms.

Finally, Moscow’s claims of U.S. foreign interference were designed to deflect responsibility from the Kremlin’s own destructive behavior on the world stage. This whataboutism is central to Russia’s information strategy. However, in this case, it’s unlikely that many will resonate with Moscow’s attempts to conflate apps stores and unsubstantiated cyberattacks with reams of evidence detailing Russian state-backed attempts to undermine democratic institutions and processes around the world.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.