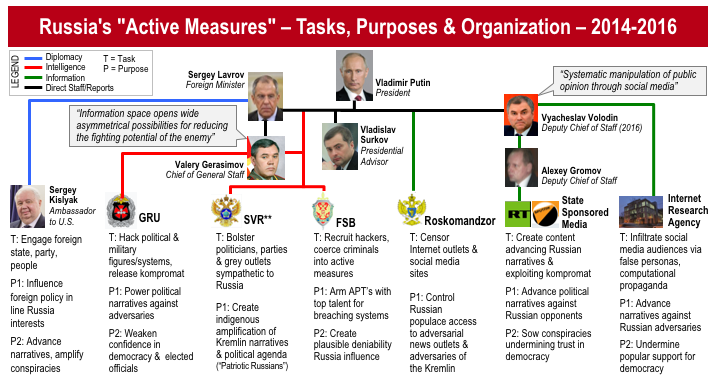

Russia’s latest iteration of the Soviet-era tactic of “active measures” has mesmerized Western audiences and become the topic de jour for national security analysts. In my last post, I focused on the Kremlin’s campaign to influence the U.S. elections from 2014 to 2016 through the integration of offensive cyber hacking, overt propaganda, and covert social media personas. Since then we have seen U.S. Special Counsel Robert Mueller indict Russia’s Internet Research Agency for their nefarious activity leading up to the U.S. presidential election of 2016. In this post, I will shift focus to the elements of Russia’s national power that execute active measures abroad, including a preview of Chapter 6, Putin’s Plan, in my upcoming book Messing With The Enemy, and an organizational chart known in military speak as a “Task and Purpose Tree.”

Source: C. Watts, Alliance for Securing Democracy

The “Active Measures” graphic demonstrates how the Kremlin employs information warfare across all aspects of their national power. Please note what this diagram is not:

-

Task Organization Chart – This diagram does not attempt to show all individuals and organizations involved with Russian Active Measures. Many more individuals in Putin’s presidential administration serve key roles and several sub-organizations serve functions as well. This chart also does not show the range of agents, contractors, and cutouts the Active Measures system employs.

-

Chain-of-Command Chart – This diagram is not meant to show every reporting relationship to Putin, but instead notes key individuals that make Russia’s Active Measure thrive – influence artists in the Kremlin machine.

This graphic instead seeks to demonstrate what military planners would call a “Task and Purpose” diagram showing key organizations and their functions in a larger system conducting information campaigns.

Active Measures and Russia’s Elements of National Power: Integrated Not Coordinated

In contrast to the West, Russia does not see information warfare as a separate or even a secondary effort in pursuit of its foreign policy goals. Instead, active measures, defeating adversaries through the “force of politics rather than the politics of force,” guide the Kremlin’s strategic approach to defeating the West. The entirety of Russia’s government understands and participates in this mindset, but in this post, I will focus on six key elements that give them a decisive edge over their adversaries on the information battlefield.

Roskomnadzor

Before undertaking the offensive on social media, Russia smartly installed an effective defense. Roskomnadzor, Russia’s Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology, and Mass Media, systematically instituted controls to censor adversarial content outlets on the Internet, creating the most vast and effective social media monitoring system in the world. Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan’s excellent book, The Red Web, offers the richest account to date of Roskomnadzor’s electronic surveillance systems riding the cyber pathways flowing into Russia to control the Russian population’s access to non-Kremlin approved information. Putin’s team knew not to go manipulating foreign populations on social media unless they could prevent the same thing from being done to them at home.

State Sponsored Media – RT, Sputnik News, and Many Others

Russia’s numerous state sponsored media outlets, namely their RT television outlets and Sputnik News wire services,1 create a constant bubble of Kremlin narratives worldwide to connect with and rally Russian populations abroad, and enlist allies amongst foreign audiences. During the run-up to the Kremlin’s active measures campaigns on Western elections from 2014 to 2016, these outlets not only advanced the Putin regime’s agenda but also tarnished opponents and promoted preferred foreign candidates in Western elections. While these state sponsored outlets may pursue immediate objectives of winning elections, they principally focus on the longer-term active measures objective of sowing doubt among foreign audiences by eroding trust in democratic institutions and confidence in elected officials. The traditional reach of these outlets into foreign populations, via television or Internet websites, was limited until they moved to social media, where attribution is more difficult for audiences to ascertain. RT’s success in growing its audience on YouTube (the channel had 2.2 million subscribers as of October 2017) came in large part through sustained sharing by affiliated social media personas — both real and fake — who brought content to foreign audiences that often did not know they were encountering Russian content.

Internet Research Agency (IRA)

Russia’s disinformation system succeeds by blending state sponsored propaganda with sustained social media engagement with targeted audiences via the Internet Research Agency. The IRA infiltrates audiences through false personas that look like and talk like the target audience, thus lowering normal cultural objections to foreign influence. Computational propaganda delivered via social bots and coordinated with social media personas inundates audiences with Kremlin-preferred content, advances Russian political and social narratives, and undermines popular support and faith in democracy through the promotion of narratives such as voter fraud, election rigging, and corruption.

Russia’s Intelligence Services

Russia’s intelligence services remain one of the country’s greatest strengths, and their strength sustains Putin’s authoritarian grip on his own population. The Kremlin sports an array of intelligence services, but their three top bureaus orchestrate active measures at home and abroad into a seamless public relations assault. Mark Galeotti at the European Council on Foreign Relations wrote an excellent and comprehensive overview of these services,2 but I will briefly touch on how Russia’s internal, foreign, and military intelligence arms integrate in the pursuit of active measures.

Federal Security Service (FSB)

Russia’s internal intelligence service garners its strength through connections to its forefathers in the Soviet KGB. Within active measures, the FSB plays several supporting active measures roles. They recruit hackers, enlisting them, directly and indirectly, in their cyber force for the pursuit of kompromat on Russian opponents at home and abroad. The FSB creates plausible deniability for the Russian government by coopting, compromising, or coercing “patriotic Russians” to do their bidding, whether they be notorious cybercriminals, international companies, or highly connected oligarchs acting as extensions of the Russian state.

Main Intelligence Administration (GRU)

Russia’s military intelligence service reached new notoriety in December 2016 when the Obama administration sanctioned them for hacking connected to the U.S. election. The GRU hacked political and military personnel and systems to gain kompromat throughout the Western elections campaign of 2014–2016. Acquisition of compromising information pilfered from Russian opponents, when released into the wild, powered political narratives influencing elections in the near term while undermining elected officials over the longer term. Among its military campaigns in Ukraine or Syria, or emerging fronts in the Baltics or Balkans, the GRU seeks out agent provocateurs who undertake physical actions, possibly including protests, rallies, and raids that seek to confirm narratives and conspiracies advanced by state sponsored information outlets and social media personas. Aggressive GRU active measures, online and on-the-ground, might have best been observed in the foiled plot on election day in Montenegro.3

Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR)

Russia’s foreign intelligence service provides the critical glue for active measures abroad. The SVR’s human intelligence assets connect with, recruit, and bolster witting and unwitting agents, foreign politicians, and political parties sympathetic to Putin’s regime. The SVR also assists in the creation and sustainment of grey information outlets stationed outside Russia, providing a veil of indigenous authenticity to what is actually a Russian influence effort. Their hidden hand has been the least explored and discussed aspect of Russia’s new active measures deployment. The SVR, depending on the country, might appear alongside political parties, create meetings with foreign officials, or possibly connect with social interest groups for infiltrating and influencing foreign policy positions sympathetic to Russia.

Russia’s Diplomatic Corps

Russia’s foreign ministries and diplomats masterfully advance the Kremlin’s active measures. Seeking to influence foreign policy, they overtly engage politicians and parties sympathetic to the Putin regime. They create engagements by which Russia’s propaganda machine can shape narratives globally by setting the agenda and advancing it first, before the other side can put forth comments on the record. Russia’s diplomats and, particularly, their cunning Foreign Minister, Sergey Lavrov, advance Kremlin narratives and kompromat-driven conspiracies. Russia’s foreign embassies have brilliantly used social media to advance their narratives against adversaries in ways no other country has successfully mastered.4

Putin’s Masters of Manipulation: The Presidential Administration

The Kremlin’s disinformation system finds success where other operations might fail because the Presidential administration consists of old hands who have worked for or alongside President Putin for years. Putin’s top team members each know their place in the disinformation system and can largely operate without direct instructions. Each knows the active measures playbook and Putin’s goals, and follows his intent without coordinating every single action of the state with every other component of the state.

Putin’s loyal top team can say or intimate Putin’s positions while also providing him a degree of removal from the actions of a deputy or proxies led by a deputy. Russia’s active measures operate as an ecosystem more than a machine, steadily progressing and keeping pace strategically despite any day-to-day setbacks. This ecosystem provides President Putin deniability in ways systematically different from the West. First, Kremlin actions occur across a web of organizations and actors that at any given moment may be competing with or contradicting each other. This distributed deniability creates the impression that President Putin could not possibly be coordinating everything, even though in aggregate the active measures machine remains on track. Putin can say hypothetically, “I didn’t tell them to do that,” because he did not, someone else did on his behalf. Second, and most importantly, Russian active measures offer the Kremlin plausible deniability by working through cutouts, corporations, oligarchs, and proxies. Each layer reports directly or indirectly to a mix of formal or informal extensions of the Kremlin, a structure designed from the outset to insulate President Putin from the aggressive active measures orchestrated by the state.

President Putin’s administration has many key players who have enabled active measures to flourish in the social media era. The Kremlin is more disciplined than Western governments about keeping its secrets close hold, but advancing a government-wide strategy requires communication and observable action. In the years leading up to their active measures assault, Russia openly advertised the formation of new psychological operations units, and key officials alluded to the Kremlin’s information offensive. Vyacheslav Volodin, deputy chief of staff to Vladimir Putin in 2016, spoke of the “systematic manipulation of public opinion through social media.” Russia’s advancements were not hidden, they were ignored.

Russia’s Chief of the General Staff General Valery Gerasimov has received the most attention for the Russian information warfare approach. The West now fears the so-called Gerasimov doctrine, based on the general’s 2013 speech where he said the “information space opens wide asymmetrical possibilities for reducing the fighting potential of the enemy.” The Gerasimov doctrine has received much attention in the press, although it is debatable whether Gerasimov himself pioneered any such approach or just displayed great foresight.5 Gerasimov deserves some credit for Russia’s world changing influence effort, but Putin’s puppet master and chief political technologist, Vladislav Surkov, should receive top billing for the Kremlin’s resurgence. Surkov, more than any other member of the Kremlin’s inner circle, understands how to create the information warfare theater by infiltrating and integrating the physical actions of the state and its proxies with disruptive narratives.

Differences between Russia and the West’s Approach to Information Warfare

The Russian approach is not dichotomous. Their mindset is not war or peace, information warfare or military conflict. It is all of the above, all of the time, in pursuit of increased power. Russia’s organization and approach to information warfare excels while the West’s struggles. The Kremlin conducts its information campaigns from a task force where there are dedicated resources and unity in mission. This is strikingly different from the whole-of-government U.S. approach and the disjointed multinational framework of the EU and NATO. Russia issues a top down intent to messaging as opposed to the laborious and stunting Western method of interagency synchronization and stakeholder coordination. Mistakes are made: Russia’s agencies compete with one another and overlap routinely occurs among its active measures cadre, but they never hesitate in pursuit of their ultimate objectives. Putin enjoys these advantages over the West because there is no free press to challenge his actions, and no need to gain buy-in from a wide range of stakeholders before execution. Russia’s information warfare is integrated not coordinated, from its inception.

More importantly, Russia’s messaging approach does not focus on synchronizing organizations but rather on layering outreach from their organizations and their proxies on different strata of the target audience. Mirroring their Soviet forefathers, Russia’s cyber-enabled social media influence operations focus on state-to-state, party-to-party, and people-to-people approaches. Whereas the United States and its Western allies predominately seek to engage in state-to-state communication, Russia inverts this pyramid, zeroing in on people-to-people strategies via social media personas, both true and false, that connect directly with Western target audiences. Traditional Soviet party-to-party approaches focused on communist political parties abroad, but today the Kremlin instead focuses on issue groups where Russia can find common ground with their adversaries. The Russian Orthodox Church, gun advocacy groups, motorcycle clubs, or anti-immigration research outlets all offer appealing avenues for the Kremlin to gain a physical and virtual foothold in the West. Finally, Russia’s state-to-state approaches in many ways trail rather than lead active measures, reinforcing successes in party and people outreach by confirming narratives and conspiracies appealing to the foreign audience they seek to win over. In summary, Russia is end state driven, not organizationally driven in the way the United States organizes its public diplomacy, information operations, and psychological operations.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.

- See, for example, Jim Rutenberg, “RT, Sputnik and Russia’s New Theory of War,” The New York Times Magazine, September 13, 2017.

- Mark Galeotti, “Putin’s Hydra: Inside Russia’s Intelligence Services,” European Council on Foreign Relations, May 2016.

- “Montenegro Coup Suspect Linked to Russian-backed “Ultranationalist” Organisation,” Bellingcat, April 25, 2017.

- For relevant examples, see Russian embassy Twitter accounts in the U.K. and South Africa.

- https://inmoscowsshadows.wordpress.com/2014/07/06/the-gerasimov-doctrine-and-russian-non-linear-war