After a contested July presidential election in which Nicolás Maduro claimed victory with 51% of the vote—amid allegations of irregularities, limited oversight, and too few international observers—Venezuela was thrown into turmoil. The Carter Center, one of the few sanctioned observers, concluded the “election did not meet international standards of electoral integrity and cannot be considered democratic.” To sustain its tenuous grip on power, Maduro’s administration must seek legitimacy from powerful allies such as Russia and China, even while attempting to mend ties with the Trump administration—an effort the latter had warmed to, then cooled on.

Digital Forensic Research Lab fellow Iria Puyosa argues that authoritarian regimes across Latin America engage in cross-regional authoritarian collaboration in the form of “strategies to manipulate media and information spaces in order to undermine weak democracies … and help like-minded illiberal leaders seize and consolidate power”. For Venezuela, this manifests in its subordinate relationships with Russia and China, hinging on mutual legitimation—endorsing each other’s elections, governance practices, and policies—and strategic amplification, in which China and Russia promote their preferred narratives and national interests in Venezuela. Yet TeleSUR, Venezuela’s premier state media outlet, does not parrot Russian and Chinese lines under duress. Rather, its editorial line frequently aligns with those of these major powers due to overlapping ideological and political goals, including a shared desire for a multipolar world that counters Western influence and sanctions. This synergy allows Venezuela to secure vital international support and reinforce its domestic legitimacy, thus preserving the Maduro administration’s foothold in power. Venezuela, in turn, recreates this same patron-client relationship with its own regional allies—a dynamic we term “media vassalage.”

In essence, TeleSUR exploits a strong press-freedom tradition in Latin America, though not Venezuela, to amplify Russian and Chinese footprints in Latin America. Russia spreads anti-US sentiment, erodes democratic institutions, and cements authoritarian rhetoric, while China uses information operations to expand influence and polish its global image. Both exploit anti-colonial sentiment to posture as champions of the “Global South”, even as Russia engages in conscription for its war in Ukraine and China uses forced labor for its Belt and Road project. To seed these narratives, Russia, China, and Venezuela rely on information laundering, the process by which problematic content is cycled through other channels, gaining legitimacy. We track this by sampling TeleSUR articles through the Information Laundromat, an open-source ASD tool, to locate related content across the web and by conducting a full-scale archival analysis of all TeleSUR articles from 2024. These findings illustrate how nested patron-client dynamics manifest through TeleSUR, reinforcing the media vassalage hierarchy.

Figure 1: A screenshot of a tweet (and translation) from a Russian government account expressing solidarity with Venezuela.

Figure 2: A screenshot of a tweet (and translation) from a Chinese government account expressing solidarity with Venezuela.

TeleSUR and the Venezuelan Media Environment

Founded in 2005 by former Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, TeleSUR is a state-funded, pan-Latin American television network supported primarily by the Venezuelan government, with contributions from the governments of Nicaragua and Cuba, and previously Bolivia, Uruguay, and Argentina. Conceived as a leftist counter to corporate Western media dominance, it expanded across Latin America, launching an English-language site in 2014. However, Argentina withdrew in 2016 over TeleSUR’s overtly pro-Chavista editorial stance. Critics, including Rory Carroll, author of “Comandante”, argue that TeleSUR had, by 2007, “mutated into a mouthpiece for … communicational and informational hegemony” and that had prioritized narratives favorable to allied governments during the Arab Spring. Venezuela’s tightly controlled media landscape features state-run outlets such as TeleSUR and VTV, pro-government intermediaries such as Globovision, and a shrinking, largely online independent press facing censorship, arrests, and digital blocks. While social media remains relatively open, it is saturated with disinformation, and platforms such as X frequently face restrictions.

Methodology: Information-Laundering Sample

This report closely follows the methodology of The Russian Propaganda Nesting Doll, ASD’s flagship report on information laundering. Analysis is divided into two periods from January to July 2024 and from July to December 2024, with a final review in January 2025. Candidate articles were identified through keyword searches in Spanish and English for Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Russia, China, and Ukraine.

The first sample was collected in July 2024 by sourcing links from Google News using queries such as Taiwan site:https://www.telesurenglish.net when:180d to bypass technical glitches on TeleSUR’s websites—a method that, while effective, skews toward advertised articles. After deduplication, we obtained 705 articles (345 Spanish-language URLs, 360 English-language URLs) published since January 2024. In early January 2025, we archived TeleSUR’s entire website and selected articles posted after July 12, 2024 whose titles were at least 70 characters, yielding an additional 659 URLs (205 in English, 453 in Spanish).

Next, we ran collected URLs through the Information Laundromat, which identifies matching or near-matching text online via Google and Bing searches (geolocated in the United States for English and in Mexico for Spanish). These queries produced over 20,000 potential matches, each with a title, description, URL, domain, and similarity score1. We filtered these matches using minimum thresholds: a single match requires an 80% average similarity score, two or three matches require 70%, and four or more require 60%. We aggregated valid results by domain, calculating median and average scores. Results are presented in Appendix 1.

Methodology: Full TeleSUR Archive

In January 2025, we scraped TeleSUR’s Spanish- and English-language websites via public WordPress endpoints, collecting all articles published since January 2023 in Spanish (14,758) and since January 2024 in English (6,722). From each article, we extracted listed sources, authors, and embedded tweets. While authors provided little insight, sources and embedded tweets revealed TeleSUR’s external influences. We aggregated these by counting how many articles each source or tweet author appeared in, noting potential undercounts due to spelling or formatting inconsistencies (for example, Sputnik vs. Sputnik Mundo). We then applied inclusion thresholds (Spanish: ≥100 sources, ≥50 tweets; English: ≥20 sources, ≥10 tweets) and labeled each entry with an affiliated state when it met the State Media Monitor’s criteria for editorial control. Results are presented in Appendix 2, and an edited release of the dataset is available on Zenodo.

Figure 3: Labeling extracted features on a sample article.

Media Vassalage in Action: How TeleSUR Launders Russian and Chinese State Media

TeleSUR’s role as a media vassal is to repackage content from Russian and Chinese state media, rebrand it with TeleSUR’s regional authority, and redistribute it, painting a picture of Russia and China as benevolent, anti-imperialist counterweights to a fractious, inept West. In return, TeleSUR benefits from the perception of solidarity with powerful allies who help Caracas resist Western sanctions, diplomatic pressure, and political isolation. Evidence of this practice appears in republished articles, embedded social media posts, and selective editorial framings that rely heavily on material from outlets such as Xinhua, RT, Sputnik, and TV BRICS.

Xinhua Synergy: China and TeleSUR

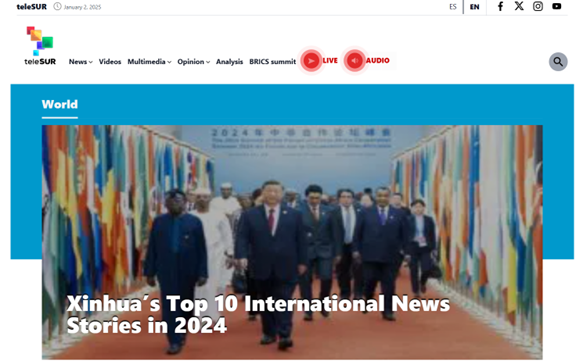

On January 2, 2025, TeleSUR English’s “World” section ran “Xinhua’s Top 10 International News Stories in 2024” as its cover story, encapsulating China’s deep influence over the network. Nearly 10% of TeleSUR’s English content can be traced to Chinese sources, and in a full archive of 6,722 TeleSUR English posts, 601 explicitly cite Xinhua. This makes Xinhua TeleSUR English’s second-most referenced source after the (legitimate) Spanish news agency EFE. Xinhua is referenced even more frequently than TeleSUR’s own Spanish service. By contrast, TeleSUR’s Spanish-language site cites Xinhua only about 200 times (1.3%).

Figure 4: TeleSUR's World page, January 2, 2025.

Both the sample and the full archive reveal substantial information laundering. In the Information Laundering Sample, TeleSUR English republished more pieces from Chinese state outlets—especially Xinhua—than all other non-Venezuelan state sources combined, with 83 near-verbatim copies of China-origin stories. These findings suggest that 12% to 16% of TeleSUR articles in English may come from Chinese sources, around 5% of which are linked directly to Xinhua. Meanwhile, TeleSUR Spanish appears to have effectively leased its “Route to China” opinion section to Xinhua: all 46 pieces there bear the byline “Por: Xinhua”. Another 37 TeleSUR articles in English (see Appendix 3) reference Xinhua indirectly either through misleading sourcing or embedded tweets. Many cover Central and East Africa, labeling the content as coming from AfricaNews (from Xinhua) or Al Jazeera (from Xinhua). Given this deceptive practice and the differential between the archive and the sample, the cited 640 Xinhua-sourced pieces are likely undercounts.

Unsurprisingly, TeleSUR leans on Xinhua to portray China as a benevolent, anti-imperialist force opposing a bloodthirsty, dysfunctional, and fractious West. About one-fifth of Xinhua-related content covers Middle East conflicts, and numerous articles endorse narratives favoring Russia, BRICS, or emerging partners such as Sierra Leone. TeleSUR English also posts feel-good or technology-focused stories clearly originating from Xinhua or People’s Daily (DW and “The Star” credited); in fact, two-thirds of their science and technology stories are copied or sourced from Xinhua (see Appendix 4). These often pair SpaceX or NASA with Chinese astronautic achievements to imply parity or superiority. Reports on Western crises such as wildfires emphasize inadequate responses, reinforcing a “dysfunctional West versus ascendant China” perspective.

From RUS to SUR: How TeleSUR Mirrors Russia

TeleSUR’s Spanish-language output heavily features content from Russian state media (TASS, Sputnik, and RT en Español) through favorable reporting, embedded social media posts, and the unedited inclusion of TV BRICS in its opinion section. While most articles citing Russian state media undergo a normal editorial process from article or brief to TeleSUR piece, Russian-affiliated tweets enjoy prominent placement in both thematically related and unrelated articles, appearing more than 500 times between the two sites. Although only 24 items (3% of the Information Laundering Sample) directly originated from Russian sources, a broader archive reveals Russia’s deep influence.

TV BRICS, a Russian-registered media outlet launched in 2017 at Putin’s behest, operates as a media intermediary focused on the BRICS+ bloc, repackaging and redistributing content through partnerships with at least 70 media organizations across Latin America, Africa, and Asia, including state-run outlets like China’s CGTN and TeleSUR. In TeleSUR, TV BRICS emerges as the largest source of laundered Russian content, contributing around 70 TeleSUR posts, half of which are from early 2024 when it dominated TeleSUR’s opinion page. Laundered articles authored by RT, TV BRICS, and Sputnik Mundo portray Russia as a stable, influential actor with key allies (Venezuela, Iran, Nicaragua) and a pivotal role in BRICS. Coverage features BRICS convenings as challenging Western hegemony, Russia’s internal politics emphasizing stable governance, scientific achievements such as the Angara-A5 rocket launch, and diplomatic gestures that reinforce Russia’s global support. While smaller in volume than Chinese content, Russia’s “media vassalage” dynamic likewise positions TeleSUR to bolster Moscow’s key narratives.

Figure 5: Link boxes from TeleSUR's Opinion page in July, where eight of 12 pieces originated from TV BRICS.

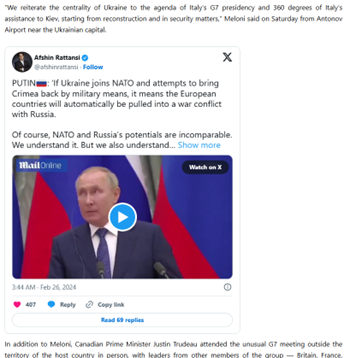

One-fifth of TeleSUR’s articles in Spanish (more than 3,200) trace to Russian state media, ranking RT, Sputnik, and TASS as TeleSUR’s second, third, and fourteenth most-cited sources. Much of this coverage focuses on restoring Russia’s image; among the 1,640 RT-sourced headlines, frequent the most mentioned countries were Russia (219), Israel (177), the United States (122), Ukraine (119), and China (57). Embedded tweets further extend Russian influence, especially for English-speaking audiences, where RT, Sputnik, and the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs were among the most frequently referenced accounts, even on TeleSUR’s original content. Embedded X handles occasionally connect to figures such as Chay Bowes, Afsin Rattansi, or Glenn Diesen, hosts and commentators tied to Russian state media, portraying them as credible analysts. By our estimate, Russian-affiliated accounts are quoted in English 109 times and in Spanish 416 times (Partial evidence in Appendix 2).

Together, these patterns illustrate TeleSUR’s subordinate role in a patron-client framework: it repackages and amplifies Russian perspectives to secure vital support, reinforcing an implicit “media vassalage” arrangement.

Figure 6: A tweet by RT host Afshin Rattansi in a TeleSUR article on security agreements between Italy and Ukraine, originally laundered from Xinhua.

Iran exerts a smaller yet notable influence on TeleSUR’s “media vassalage” dynamic. Its Spanish-language outlet, HispanTV, is cited nearly 500 times—primarily in stories on Middle Eastern conflicts (Israel appears 207 times, Palestine 43, Yemen 32, and Syria 21). In TeleSUR English, Iran’s footprint is less pronounced, with around 90 references split among HispanTV, PressTV, and IRNA. Meanwhile, the Iranian state media account @PalHighlight that focuses on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict features prominently in both Spanish- and English-language coverage.

Qatar’s Al Jazeera, whose collaboration with TeleSUR dates to a 2006 cooperation agreement, ranks comparatively high, as the fifth-most cited outlet in TeleSUR English and the second-most referenced non-Venezuelan state media entity after Xinhua. Its @AJEnglish handle is TeleSUR English’s second-most embedded account, trailing only TeleSUR’s own.

Second-Order Information Laundering: TeleSUR as Benefactor

Just as TeleSUR depends on Russia, China, and to a lesser degree Iran for material and political support, it also acts as a patron to the state media of smaller allies, particularly Nicaragua and Cuba, as well as other sympathetic outlets. Through second-order information laundering, TeleSUR’s content is repackaged by local media—such as Nicaragua’s Barricada or Cuba’s Prensa Latina—often with minimal attribution. These downstream partners mimic TeleSUR’s own relationship with its patrons: official narratives, whether about elections, foreign policy, or geopolitical alliances, cycle through overlapping news ecosystems that originate from the more powerful partner. This network reinforces shared ideological positions and creates a counterweight to Western-dominated global media structures. By extending the “media vassalage” playbook it learned from Moscow and Beijing, TeleSUR solidifies its regional influence, bolsters regime survival, and amplifies narratives that challenge US and Western hegemony. This strategy positions TeleSUR as a linchpin in a broader geopolitical project: legitimizing authoritarian allies and insulating them from international isolation under the guise of promoting multipolarity and anti-imperialism.

Three broad categories of content-laundering sites emerge: aggregators, politically aligned, and economically motivated, while mirror sites and other outliers also regularly appear.

Political and Economic Reposters

TeleSUR’s English-language content has limited direct uptake but is redistributed by regional and ideologically aligned outlets, reinforcing the “media vassalage” model. For example, the St. Vincent Times published more than 200 articles, including a weekly column from Venezuela’s embassy, many copied from TeleSUR. These articles promote Venezuela’s foreign policy and diplomatic efforts while building confidence in recent elections. In Cuba, Prensa Latina lightly rewrites TeleSUR’s English-language pieces without attribution, focusing on foreign affairs and legitimizing Venezuela’s electoral process. Additional ideologically aligned “launderers” emerged in the second sample, including an Iranian Marxist-Leninist site 10 Mehr Group and Big News Network, known for syndicating state media via faux local platforms, through shared Xinhua content.

Spanish-language outlets show even broader patterns of TeleSUR content-laundering and thus “vassalage”. Nicaragua, a TeleSUR sponsor, republishes its articles across state-owned channels (Diario Barricada, Canal 8, El 19 Digital) with 35 instances identified out of 565 links, mostly involving local references. Prensa Mercosur, the press wing of the South American economic union MercoSur reposted 29 TeleSUR stories, while Globovision, a Venezuelan outlet under US sanctions, added six. Here, TeleSUR’s own practice of amplifying Russia and China is mirrored back: these sites become junior partners, laundering TeleSUR content under local or pan-Latin bylines to bolster Maduro’s legitimacy and related political narratives.

Most small- to medium-scale laundering sites appear at least nominally independent and ideologically sympathetic: Mexico’s Mision Politica, Argentina’s Resumen Latinoamericano, plus Venezuelan outlets La Prensa de Caracas and Aporrea. Their reposts primarily highlight stories on Gaza, China, and Russia, but avoid election topics. The Chavista blog Pueblo Combatiente likewise relies on TeleSUR, except for editorial sections and Ukraine coverage sourced from Sputnik Mundo.

Some local news outlets seem driven more by content needs than ideology, including Nicaragua’s Canal 2, Peru’s idesotv[.]com, and Argentina’s Canal Cuatro Posadas. Websites like Agalena.com[.]ar and PeorParaElSol.com[.]ar similarly feature TeleSUR excerpts with minimal context, suggesting economic motives. Across these varied platforms, TeleSUR’s content is rebranded and redistributed, exemplifying a patron-client “media vassalage” structure that deepens the Maduro administration’s regional and international foothold.

TeleSUR and Social Media

This patron-client dynamic extends to social media platforms, where TeleSUR’s content is recycled by smaller outlets or ideologically aligned channels. Instagram and X are the primary nodes.

TeleSUR posts frequently, and sites such as El Universal (with substantial followings), Nicaragua’s El 19 Digital and Canal 8, and semi-affiliated reposters (Cubasi, Prensa Mercosur) amplify TeleSUR’s coverage, thereby reinforcing “media vassalage” online. Other networks—YouTube, TikTok, DailyMotion, Pinterest, Reddit, and LinkedIn—show lower but still notable traces of information laundering, often through partially or fully unattributed TeleSUR reprints.

Some reposts illustrate complex, multi-hop laundering. A Reddit post about Russia’s Angara-A5 rocket launch, for example, copied a TeleSUR English-language article that itself drew from TV BRICS, which cited a TeleSUR Spanish piece likely derived from RT. The Information Laundering Sample also revealed scattered examples on Facebook and TikTok—where text-based search results were harder to parse—and two instances on YouTube. In one case, a YouTube video’s description duplicated a TeleSUR article that originally came from Xinhua.

Though not all content sharing equals laundering, posts using entire segments without attribution constitute unambiguous evidence of repackaging TeleSUR for new audiences. Even minor engagement—such as a repost on r/UkrainianConflict that garnered backlash—demonstrates how such narratives can migrate across ideological lines. Platforms such as Pinterest and LinkedIn, where TeleSUR and Prensa Mercosur maintain active accounts garnering 300,000 and 239,000 views per month, respectively, further bolster TeleSUR’s regional and international reach, deepening the cycle of information laundering and fostering media vassalage.

Figure 7: A screenshot of TeleSUR's Pinterest profile from January 2025, showing their more than 300,000 monthly viewers.

Conclusion

TeleSUR’s alignment with Russia and China belies a convergence of autocratic state media narratives laundered and disseminated through Venezuelan channels. As Maduro tries to secure power amid internal turmoil and international scrutiny, TeleSUR serves as a crucial tool in his arsenal—an echo chamber that amplifies and legitimizes the narratives of foreign powers with vested interests in a sympathetic Venezuela, then echoes that message to Venezuela’s sphere of influence. The message: authoritarian regimes are bastions of stability and progress, while Western democracies are chaotic and untrustworthy. Thus, a striking contradiction emerges: Venezuela has historically positioned itself as a beacon of anti-imperialism and social welfare. Yet the Maduro administration has effectively mortgaged part of its autonomy to the imperial ambitions of other states, adopting the propaganda playbook it once denounced.

In effect, TeleSUR’s news pipeline illustrates a media vassalage dynamic in both directions: it acts as a beneficiary of Russia and China while simultaneously serving as a benefactor to smaller state allies (Nicaragua, Cuba, and others), creating a layered ecosystem of mutual dependence. Through this framework, media channels across Latin America are drawn into a patron-client hierarchy of shared narratives, further tightening the Maduro regime’s tenuous grip on power at the cost of genuine journalistic independence. As Puyosa and the National Endowment for Democracy recommend, the antidote to this authoritarian influence on media in Latin America is strengthening and refocusing civil society to expose and dismantle these narratives through robust fact-checking, independent journalism, and regional coalitions.

This article contains substantial research contributions from James Conway and Marcos Sebares Jiménez-Blanco. An archive of TeleSUR’s content is available on Zenodo.

For more details on similarity scores, please see the “about” section on the information laundromat tool: Information Laundromat – About

Appendix 1. Selected Data Frames from Sample

Below are selected samples from the filtered and aggregated results. TeleSUR and other Venezuelan state media domains, along with low-volume domains (fewer than three matches unless otherwise relevant), have been excluded.

Appendix 2. TeleSUR Sources and Embedded Tweets

Appendix 3. Articles Where Xinhua is Mentioned, but Not Attributed

Appendix 4. Xinhua-Linked Science and Technology Articles

Appendix 5. Information Laundering Matches on Social Media

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.