Was Ayatollah Khamenei behind a now-banned Twitter account that threatened to assassinate former President Trump?

Recently, Twitter permanently suspended an account—@Khamenei_site–following a tweet that was widely interpreted as a thinly veiled threat to assassinate President Donald Trump in retaliation for the killing of Iranian General Qasem Soleimani in Baghdad last year. After initial reports linked the account to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Twitter clarified that the account had been banned not only because it violated Twitter’s abusive behavior policy but because it was “fake.”

But as the Associated Press and others noted, the @Khamenei_site account had frequently posted unedited excerpts from Khamenei’s speeches, had been followed and retweeted by two of Khamenei’s other official accounts, and had linked to the supreme leader’s website, which featured the same threat against Trump: an image of a golfer in the shadow of a drone with the caption “revenge is certain.”

Threatening image posted to Twitter and a retweet of the @Khamenei_site account from Khamenei’s official Farsi-language account.

By the Numbers

Analysis of data collected by the Alliance for Securing Democracy’s Hamilton 2.0 tool provides further evidence that the @khamenei_site account was, if not officially sanctioned by the supreme leader, linked in some way to the regime. Prior to its suspension, @Khamenei_site had been retweeted more than 80 times by 19 different accounts connected to Iranian government officials and state media outlets, including Iran’s Permanent Mission to the UN; Iranian embassies in Ukraine, Slovenia, and Niger; and the state controlled Tasmin and Fars News Agencies. More significantly, the now-banned account was retweeted more than 35 times by Khamenei’s Farsi-language account over the last seven months, with the first retweet coming in July 2020, the same month the @Khamenei_site account was created. This activity makes it difficult to suggest that the @Khamenei_site account was truly a “fake,” as that would mean it somehow managed to dupe the very person it was supposedly impersonating. A more likely scenario is that the account was an unofficial but regime-endorsed asset, which raises questions about whether Twitter should consider that a distinction without a difference when confronting the regime’s continued efforts to circumvent platform policies.

What We’re Seeing on Hamilton 2.0

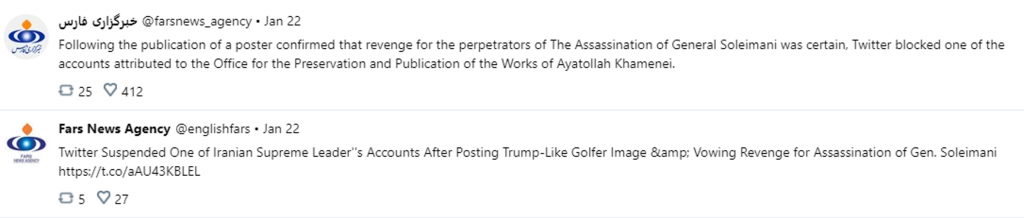

Since the @Khamenei_site account was shut down by Twitter on January 21, Iranian diplomats and state media outlets have been largely silent on the matter, with only two references to the incident appearing on the English and Farsi-language accounts of Fars News Agency. Significantly, however, both tweets seemed to affirm that the account was, in fact, connected to the supreme leader.

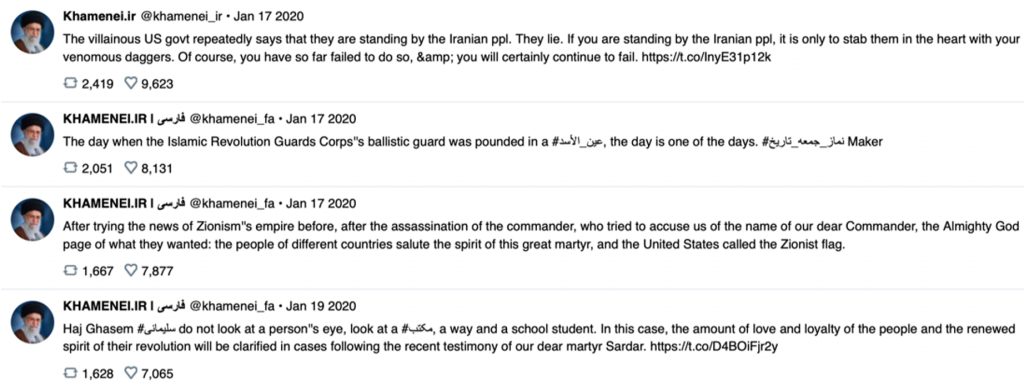

If there is indeed a connection to the supreme leader, the fact that Khamenei and other Iranian officials have not protested the takedown is telling. It suggests, perhaps, a strategy to distance the supreme leader from the relatively low-profile @Khamenei_site account in order to avoid a universal suspension of Khamenei’s entire Twitter operation. That threat, in fact, seems to have triggered a clean-up operation of potentially offending posts on Khamenei’s other accounts. In the days following the suspension, for example, Khamenei deleted at least nine recent tweets—one from his English-language account and eight from his Persian-language account—from the platform. Nearly all were related to Soleimani and/or conflict with the United States.

Examples of recently deleted tweets from Khamenei’s Farsi-language account.

Why It Matters

This saga has, of course, played out in the wake of Twitter’s decision to permanently ban former President Trump from its platform. That move reignited calls to ban Khamenei and other Iranian officials from Twitter, not only because of a perceived double-standard in Twitter’s enforcement but also because of Iran’s decision to ban its own citizens from using the platform. If the @Khamenei_site account were conclusively linked to the supreme leader, its clear violation of Twitter’s abusive behavior policy could be used to justify the removal of the more than a dozen accounts Khamenei uses to reach audiences around the globe.

More broadly, this case highlights the enormous challenges of attribution—particularly in cases where suspensions can have significant geopolitical ramifications. While Twitter has not provided details about how it reached its conclusion that the account was a fake, one must assume that their determination was based on internal signals (for example, IP addresses or registration details) that pointed away from the Office of the Supreme Leader. If this were indeed the case, it would suggest—given the clear evidence of official Iranian engagement—that the @Khamenei_site account may have been specifically set up with plausible deniability in mind. Going forward, this raises important questions about how platforms should negotiate policy responses to accounts that live in the ill-defined gray-zone of ambiguous government control.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.