A report from the Alliance for Securing Democracy and the Institute for Strategic Dialogue by Iris Boyer, Zoé Fourel, Sasha Morinière, Bret Schafer, and Etienne Soula.

Introduction

On March 2, 2022, Russian state media outlets RT and Sputnik were banned from European information spaces by EU authorities in reaction to “unprovoked and unjustified military aggression by Russia against Ukraine.” Both operators are prohibited from broadcasting in or to the EU based on a decision meant to counteract the Russian government’s orchestrated information manipulation and disinformation campaigns. A series of measures taken by digital platforms have followed the EU’s decision, further limiting the availability of Russian state media outlets to audiences both inside and outside the EU.

This report looks at the impact of the suspension of RT and Sputnik France within the French information landscape by reviewing social media data collected and analyzed by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) and the Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD). In addition to the quantitative analysis conducted by both organizations, this report combines independent analysis conducted by ISD and ASD highlighting, respectively, the response to the ban from French online fringe communities across different social media platforms and the efforts of proxies—most notably, the Russian Embassy and Chinese state media outlets and officials—to keep Russian narratives circulating in the French information ecosystem.

Methodology

ISD has manually reviewed reactions on different mainstream platforms (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) and on more alternative online spaces (Telegram, Odysee) since the announcement of the EU suspension of RT and Sputnik on February 27, 2022. ISD has gone through hundreds of pages and groups on Facebook, 100 Instagram accounts, and 91 French Telegram channels. These accounts were selected as they have actively shared disinformation, conspiracy theories, or extremist discourses.

To establish the scale of these discussions, ISD used social network listening tools Brandwatch (to analyze Twitter content) and CrowdTangle (to review Facebook and Instagram content). ISD researchers developed a list of keywords related to the suspension of RT and Sputnik. ISD then extracted the data associated with this list and conducted a database analysis on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

ASD reviewed data collected on its French Election Dashboard, an open-source tool that monitors Chinese and Russian government officials and Chinese, Russian, and other state-backed media outlets targeting audiences in France on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and state-sponsored websites.

Main Findings

- The implementation of EU measures clearly impacted the activity and reach of RT and Sputnik France on Facebook, Twitter, and Telegram. The volume of publications posted by both outlets has dropped significantly, as have interactions with the content posted by their accounts on social media.

- There are some clear limitations to this ban: ISD has identified ways to circumvent RT and Sputnik’s geo-blocking measures, notably by modifying certain functionalities of social media platforms. In addition, a multitude of solutions have been promoted online (for instance, the use of a VPN) to circumvent these restrictions. Thus, it is still possible for European audiences to access RT and Sputnik despite the measures in place.

- ASD has noted that the sharp decline in Russian state media’s production and reach on social media has coincided with a significant increase, particularly on Twitter, in the posting activity of and engagements with the social media accounts affiliated with the Russian Embassy in France. Chinese state media and the Chinese Embassy in France have also filled the void, parroting Russian talking points and signal boosting Russian accounts, though with somewhat limited success.

- ISD has also observed calls to migrate to alternative online spaces such as VK, which creates a risk of audiences moving to more extreme online spaces that have little content moderation. However, these calls have not led to a mass movement, in contrast with other European branches of RT (RT DE or RT Spanish). The suspension of RT and Sputnik in France has fueled conspiracy theories and anti-establishment rhetoric, echoing narratives spread about COVID-19 and the French government’s sanitary restrictions. These narratives were, perhaps not coincidentally, identified by ASD as the focus of RT and Sputnik messaging prior to the war and the subsequent EU ban.

Understanding the Impact of the RT and Sputnik Ban in France

The effects of the EU’s RT and Sputnik ban, as well as social media platforms’ restrictions, are already visible. ISD has witnessed a clear activity and traffic drop on both websites’ social media accounts. In a French context, the most visible effect of the EU’s decision is the complete shutdown of the media outlet Sputnik France, which has not published any articles on its website (fr.sputniknews.com) and has barely used its social media accounts since March 4, 2022. Only its Telegram channel, which was renamed “Fil à Retordre” to avoid being blocked by the platform in France, continued to publish content until March 17. The views on Sputnik France’s Telegram channel increased between February 28 and March 6 (741,032 views), before dropping by about 70 percent on March 7, falling to 212,400. Since March 18, the channel has not exceeded 10,000 views, according to data gathered by TGstate.

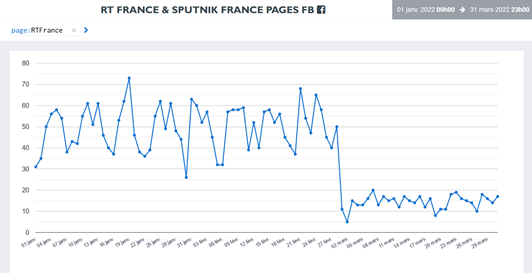

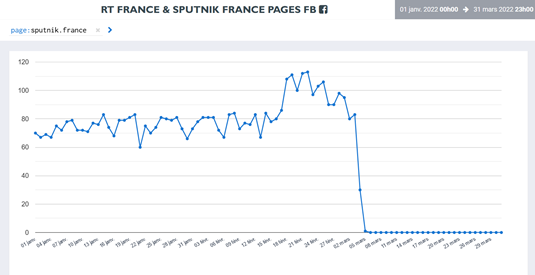

The EU decision also impacted RT and Sputnik France’s social media activity. From January 1 to mid-February, both RT France and Sputnik France’s Facebook accounts posted 100 to150 times. After mid-February, both pages increased to 150 to 175 posts a day, with a clear drop in early March as restrictions were implemented. The graph below shows limited activity from March 5 onwards, with only 8 to 20 posts per day. Sputnik, which was responsible for the increase in posts in February, has completely stopped broadcasting.

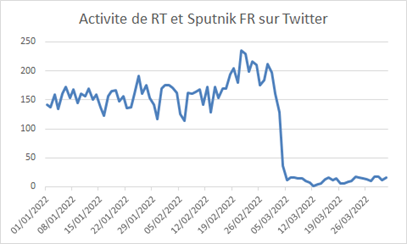

RT and Sputnik France’s Twitter accounts show similar patterns, with a clear drop in activity in early March (Figure 3). According to ASD’s analysis, RT and Sputnik France’s Twitter accounts in the last week of March produced less than 10 percent of the tweets they produced in the last week of February. As with Facebook, Sputnik France stopped producing Twitter content on March 4.

Figure 1: The volume of publications on RT France’s Facebook page from January 1 to March 31,2022. Source: Data and graphs from the institute of Geopolitics of the Datasphere (GEODE), extracted with Visibrain.

Figure 2: The volume of publications on Sputnik France’s Facebook page from January 1 to March 31,2022. Source: Data and graphs from the institute of Geopolitics of the Datasphere (GEODE), extracted with Visibrain.

Figure 3: Volume of publications on the RT and Sputnik France Twitter accounts from January 1 to March 31, 2022.

The graphs below show the activity and engagement metrics of both RT and Sputnik France pages before and after the EU and social media platforms imposed restrictions. The first period extends from February 1 to February 28, 2022, and the second from March 1 to March 31, 2022.

Figure 4: Activity and engagement metrics of the RT France Facebook page from February 1 to February 28, 2022. Source: Infographic from GEODE and data collected from Visibrain.

Figure 5: Activity and engagement metrics of the RT France Facebook page from March 1 to March 31, 2022. Source: Infographic from GEODE and data collected from Visibrain.

Figure 6: Activity and engagement metrics of the Sputnik France Facebook page from February 1 to February 28, 2022. Source: Infographic from GEODE and data collected from Visibrain.

Figure 7: Activity and engagement metrics of the Sputnik France Facebook page from March 1 to 31, 2022. Source: Infographic from GEODE and data collected from Visibrain.

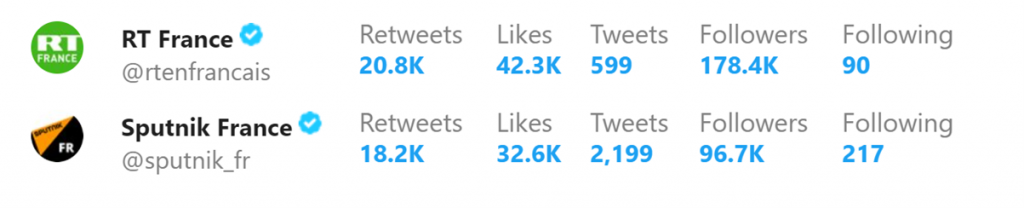

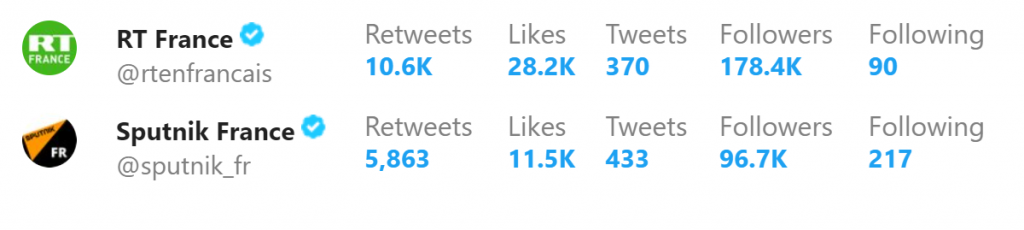

The charts below show the activity and engagement metrics of both RT France and Sputnik France’s Twitter accounts before and after the EU and platforms imposed restrictions. The first period extends from February 1 to February 28, 2022, and the second from March 1 to March 31, 2022. There was a roughly 50 percent decline in RT and Sputnik France’s engagement metrics from February to March; although, the decline was even more dramatic towards the end of March.

Figure 8: Metrics of activity and engagement of the RT France and Sputnik France Twitter accounts from February 1 to February 28, 2022. Source: Metrics from ASD’s Hamilton 2.0 dashboard.

Figure 9: Metrics of activity and engagement of the RT France and Sputnik France Twitter accounts from March 1 to March 31, 2022. Source: Metrics from ASD’s Hamilton 2.0 dashboard.

Responses and Tactics in Reaction to the Suspension of RT France and Sputnik

ISD has identified several tactics deployed by fringe communities to continue accessing RT and Sputnik France from France.

- Both on Facebook and Telegram, users shared both general advice about how to use a VPN and links to specific VPNs across channels and groups.

- Certain actors also promoted the use of Tor.

- Screenshots of articles published by RT France were also shared on Telegram.

- The suspension can be circumvented by changing some social media platform functionalities.

- Sputnik France also tried to avoid the suspension of its activity on Telegram, as it re-named its Telegram channel “Fil à Retordre” shortly after the suspension. This channel has subsequently been shut down by Telegram.

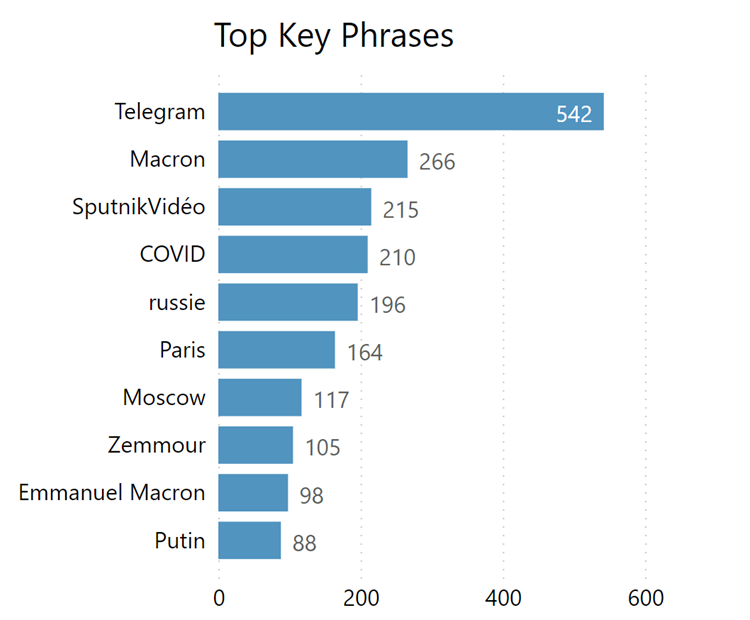

Actors from the French fringe online ecosystem have mobilized to protest the suspension of RT and Sputnik France. This was particularly the case for far-right political figures François Asselineau and Florian Philippot and his movement Les Patriotes. A petition against the ban was launched and promoted across Philippot’s social media channels, gaining limited traction. As the suspension was implemented, ISD observed a call on mainstream platforms for users to migrate to other fringe online spaces (namely Russia-based social media platform VK). This was even the case on Telegram, which is generally considered a safe haven due to limited content moderation. ASD also observed that RT and Sputnik France’s Twitter accounts had aggressively promoted their Telegram channels before the ban, as evidenced by the fact that “Telegram” was the most used key phrase by the two accounts from January 1 to February 28, 2022 (Figure 10).

Further analysis would be required to understand the platform migration dynamics across Europe in reaction to the suspension of RT and Sputnik.

Figure 10: Top key phrases used by the RT France and Sputnik France Twitter accounts from January 1 to February 28, 2022. Source: ASD’s Hamilton 2.0 dashboard.

The RT and Sputnik Ban Revives and Fuels Anti-Establishment Rhetoric and Conspiracy Theories

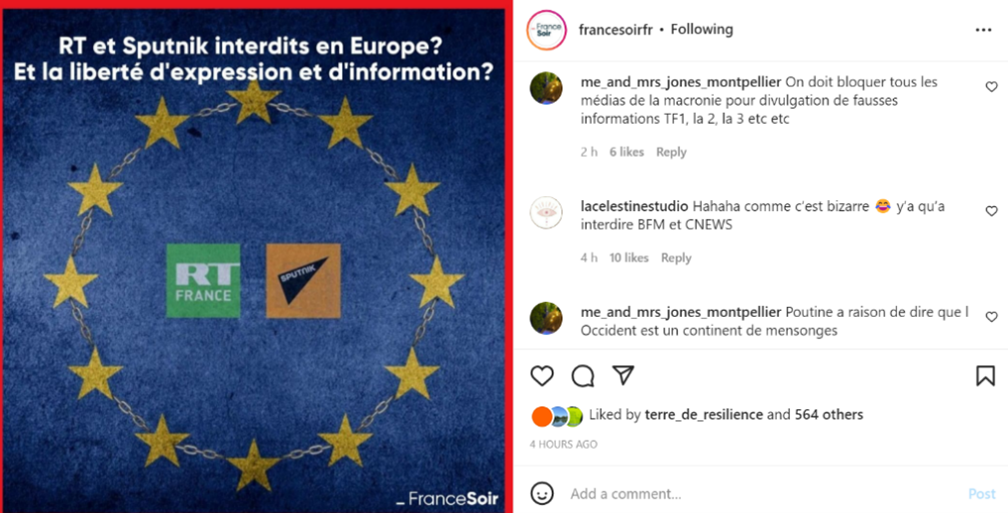

The EU’s decision to ban the broadcasting of Sputnik and RT has generated hostile reactions from the French “complosphere” (conspiracist ecosystem) and extremist actors, who are framing this decision as a symptom of current attacks on freedom of expression and as an authoritarian drift orchestrated by the French government and European institutions.

Florian Philippot, leader of the far-right movement Les Patriotes, said the ban is “a precedent against freedom of expression, which heralds a terrifying future of arbitrariness and censorship.” Similar rhetoric was used within some channels affiliated to the “complosphere” on Telegram.

Figure 11: Examples of posts.

Some outlets that have previously been identified as sharing disinformation have also amplified the narrative that the suspension goes against fundamental rights and freedom of expression. These outlets include the controversial news outlet France Soir, which NewsGuard has described as the “main French website amplifying disinformation in 2021.” The anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist website Le Grand Soir, hosted by Viktor Dedaj, which has shared conspiracy theories on the war in Ukraine, has also contributed to the dissemination of this narrative.

Figure 12: Example of a post.

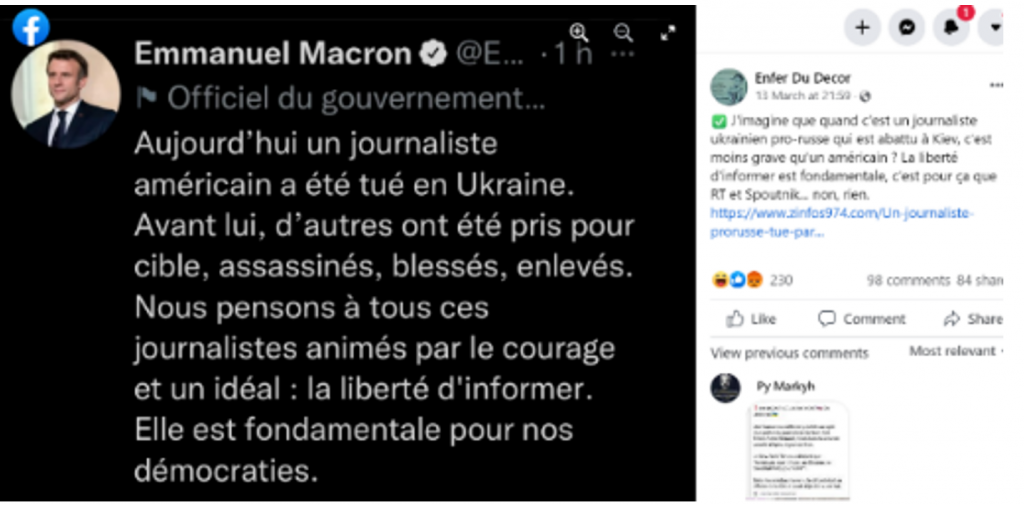

This narrative was prevalent in French fringe communities’ online reaction to the EU’s decision to suspend RT and Sputnik. On Facebook, every one of the 20 most interacted with posts mentioning RT France and Sputnik France referred to this decision as “censorship.” A majority of these publications also denounced a supposed “dictatorship” implemented by the French government and EU institutions, according to CrowdTangle data.

This conspiracy theory echoes one of the most popular of the covid-19 pandemic: that the French government was creating a “health dictatorship” (“dictature sanitaire” in French). Regular monitoring of Facebook groups that opposed the French government’s sanitary restrictions during the pandemic (especially the vaccination pass) enabled ISD to observe a shift starting on February 24, 2022 (the day of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine). These communities, which mainly posted about COVID-19 up to the Russian invasion, pivoted to the war in Ukraine, sometimes spreading pro-Kremlin rhetoric. ISD also found hateful speech in publications condemning the suspension of RT and Sputnik, including antisemitic, homophobic, and transphobic rhetoric, such as conspiratorial content aimed at Brigitte Macron.

Figure 13: Example of a post.

Figure 14: Example of a post.

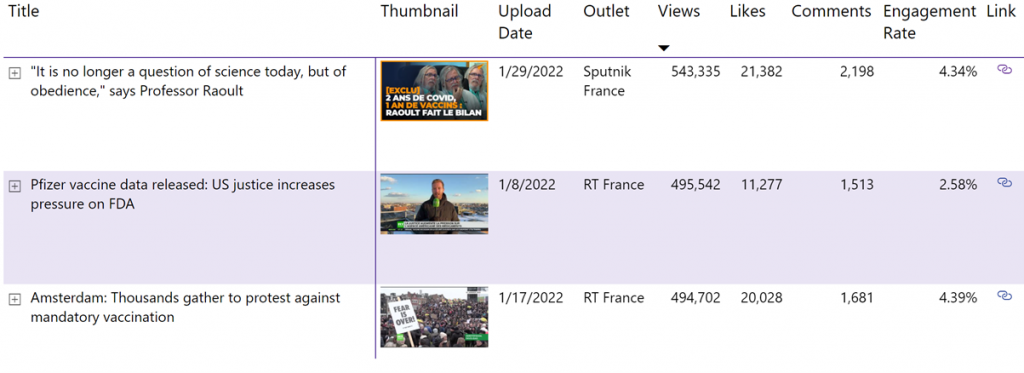

Perhaps not coincidentally, ASD identified vaccine skepticism and anti-sanitary measures as the narratives most regularly featured in RT and Sputnik France’s most interacted, viewed, and engaged-with content across a variety of social media platforms prior to the war in Ukraine and the EU ban. On YouTube, for example, all 10 of the most viewed RT France and Sputnik France videos in January 2022 featured content critical of sanitary measures or vaccines. On Twitter, #passvaccinal was the second most used hashtag by RT France and Sputnik France’s accounts in January, behind only #russie.

Figure 15: The three most viewed RT France and Sputnik France videos on YouTube in January 2022. Source: ASD’s Hamilton 2.0 dashboard.

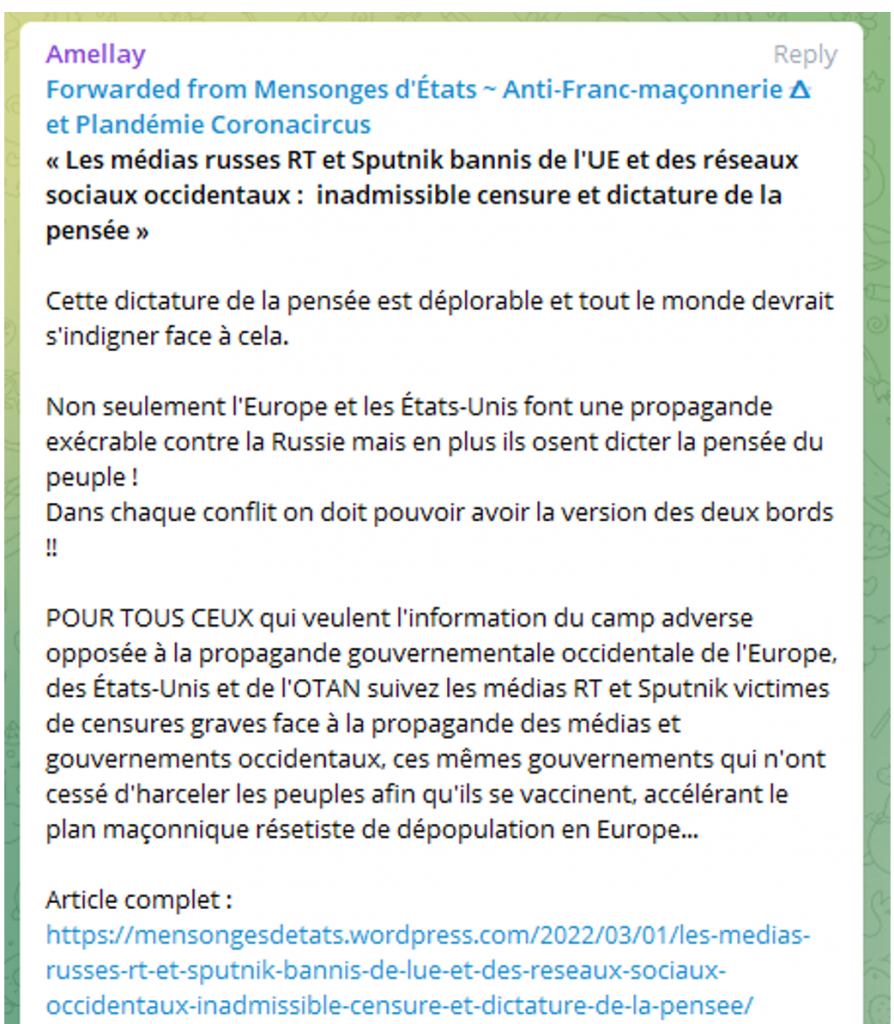

This EU decision has been used to fuel several conspiracy theories, including QAnon and anti-vaxx conspiracy narratives. These communities have repurposed the ban of RT and Sputnik to fuel their overall narrative, using this new event to promote various conspiracy theories.

Figure 16: Example of a post.

Russian Diplomats and Chinese Propaganda to the Rescue

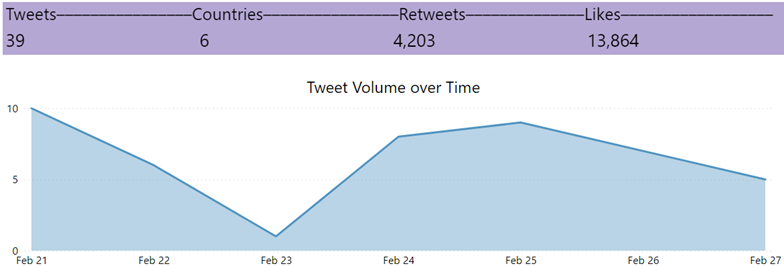

With Russian state media struggling to remain relevant in France after the EU ban, ASD has identified other actors that have stepped in to keep Russian narratives about the war in Ukraine in the French public debate. First and foremost, the messaging out of the Russian Embassy in Paris has undergone a noticeable metamorphosis over the course of March. The formally inconspicuous diplomatic representation has become the key propagator of pro-Russian narratives on Twitter in France.

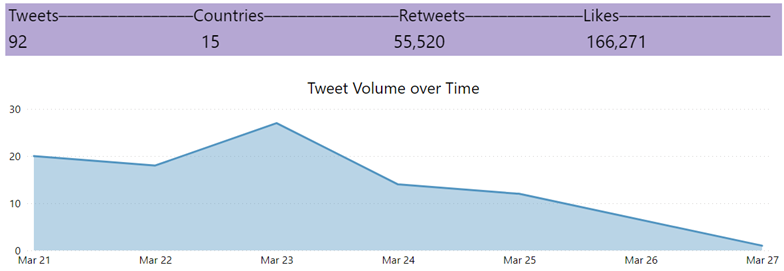

In the last week of February, the embassy published 39 tweets that generated 4,200 retweets and less than 14,000 likes. In the last week of March, the embassy account published 92 tweets that generated more than 55,000 retweets and more 166,000 likes.

Figure 17: Metrics of activity and engagement of the Russian Embassy in France’s Twitter account from February 21 to February 28, 2022. Source: ASD’s Hamilton 2.0 dashboard.

Figure 18: Metrics of activity and engagement of the Russian Embassy in France’s Twitter account from March 24 to March 31, 2022. Source: ASD’s Hamilton 2.0 dashboard.

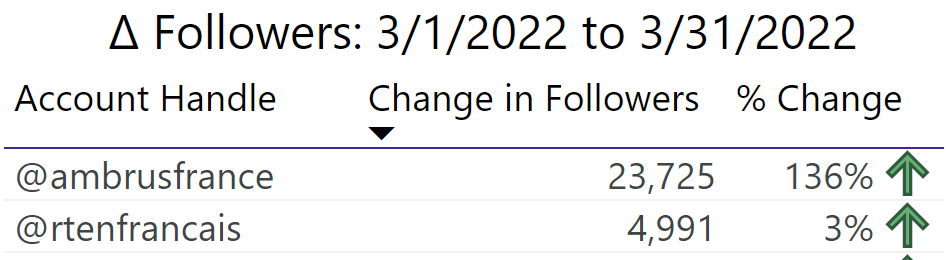

The Russian Embassy in France’s account has also seen a dramatic increase in followers on Twitter since March 1, 2022. During the month of March, the embassy’s Twitter followers more than doubled, dwarfing RT France’s increase in followers during the same period.

Figure 19: Change in followers of the Russian Embassy in France and RT France’s Twitter accounts from March 1 to March 31, 2022. Source: ASD’s Hamilton 2.0 dashboard.

There also has been a significant shift in the narrative focus and tone of the embassy’s account. In January, the embassy’s tweets focused on covering high level diplomatic meetings or cultural diplomacy, such as tweets highlighting Russia’s “majestic landscapes.” In the last week of March, the embassy’s messaging was focused on denigrating U.S. warmongering, accusing Ukrainians of atrocities in their own country, and promoting Russian “humanitarian aid” to Kharkiv. The French government noted the change and in March summoned the ambassador over two cartoons tweeted by the embassy the previous day. Both cartoons have since been taken down from the embassy’s account.

Figure 20: Example of posts from the Russian Embassy in France’s Twitter account.

The new, overtly provocative tone of the Russian Embassy in France’s messaging is reminiscent of what the Chinese Embassy in Paris has been doing for years. The Chinese ambassador in France is a self-avowed “wolf warrior” who has also been summoned by the French Foreign Ministry on several occasions over his embassy’s unacceptable communications, notably around the French authorities handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the beginning of March, the Chinese Embassy in Paris has consistently supported Moscow’s line on Ukraine, notably by attacking the United States over supposedly nefarious bio-labs it funds in Ukraine, or by amplifying concerns about rampant “Russophobia” in France. On multiple occasions, the Chinese Embassy in France has also retweeted its Russian counterpart, including one tweet claiming that the Bucha massacre had been staged by U.K. intelligence.

Figure 21: Example of the Chinese Embassy in France retweeting a conspiracy theory from the Russian Embassy in France Twitter account.

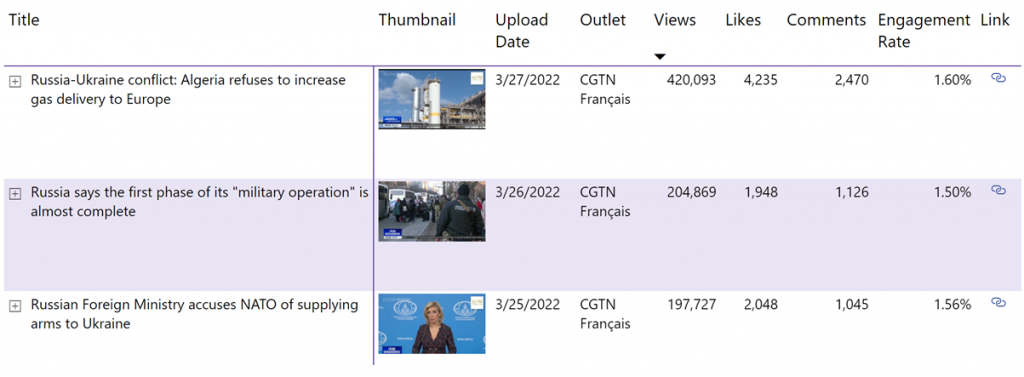

In addition, French-language Chinese state media have also carried water for Moscow, portraying Russia as having the upper hand in Ukraine, despite Western sanctions. For instance, CGTN Français’ top performing videos on YouTube in the last week of March were a story about Algeria refusing to provide more gas to Europe to offset Russian imports, the Russian Foreign Ministry announcing “the first phase of its ‘military operation’ [was] almost over,” and the Russian Foreign Ministry accusing NATO of supplying weapons to Ukraine. This is consistent with Chinese diplomats and state media’s pro-Russian messaging globally.

Figure 22: The three most viewed RT France and Sputnik France videos on YouTube in January 2022. Source: ASD’s Hamilton 2.0 dashboard.

While French-language Chinese state media’s embrace of some Russian talking points on Ukraine is significant, their weight should not be overestimated. On YouTube, CGTN Français’ content generates only a fraction of the numbers RT France or Sputnik France videos used to garner prior to the March takedown. Even on Facebook, where CGTN Français boasts an impressive 20 million followers, its interaction numbers are but a fraction of what Russian state media used to generate. In February, the last month when RT France operated unhindered on Facebook, the Russian outlet’s more than 1,400 posts generated 950,000 interactions, while CGTN Français’ 908 posts only generated less than 185,000 interactions. Even in March, when RT France took a serious hit on the platform, its interaction rate was still ten times higher than its Chinese counterpart’s.

ASD has also observed a migration of current and former RT and Sputnik hosts, contributors, guests, and pundits to domestic French media outlets. For instance, Pierre Gentillet, a regular guest on RT France who is affiliated with the Franco-Russian Dialogue, an organization linked to sanctioned Putin ally Vladimir Yakunin, now frequently appears as a commentator on French TV channel CNEWS. An even more striking example of RT voices being given a platform by French media is a show on radio station Sud Radio. In March, that show consistently chose to invite former RT France talking heads to comment on the Russian war in Ukraine. For instance, the March 4 episode of the show invited Charles Gave, a frequent commentator on RT France, and Xenia Fedorova, the director of the Russian state media outlet, to comment on the EU’s sanctions on Russia. The title for the YouTube recording of the episode is “Russia can hold out for two years, France for two months!”

Former RT talking heads are not the only pro-Russian voices in the French public debate. In an interview by newspaper Le Figaro, Franco-Russian author Andrei Makine explained that the “Neo-Nazi” Azov battalion makes the Kremlin’s propaganda “more credible for Russians” and that “the West” seeks to “trigger the collapse of Russia, the impoverishment of its people.” The Chinese Embassy in France amplified Makine’s interview in mid-March. Marginal politicians with very significant social media followings, such as François Asselineau or Florian Philippot, are another vector of dissemination of pro-Russian narratives. In March, Asselineau repeated Russian conspiracy theories tying Hunter Biden to the financing of a “biological weapons program” in Ukraine to his 143,000 Twitter followers.

Conclusion: Reduced Activity, Increased Suspicion

The suspension of RT and Sputnik by European authorities has reduced RT and Sputnik France’s activity on social media, as well as impacted their engagement and reach, which has significantly dropped since the implementation of the EU decision on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Telegram. Nonetheless, ISD has identified several ways that fringe actors have been able to circumvent the suspension of RT and Sputnik. Fringe communities tied to the French “complosphere” as well as extremist actors have actively been sharing solutions to continue accessing RT and Sputnik France from France. This decision has also fueled anti-institutional rhetoric, and it has been re-purposed by conspiracy communities to further promote other conspiracy narratives such as QAnon or anti-vaccination conspiracy theories.

The suspension of both these Russian state media entities calls into question their future role within the French information ecosystem. This decision counteracts RT and Sputnik France’s efforts to establish themselves in France, as both outlets had gained visibility in recent years, particularly following their coverage of the Yellow Vest crisis in the case of RT France. However, the activity of RT and Sputnik France cannot only be understood from a Eurocentric perspective, as the fourth country in which Sputnik France achieves its largest audience is in Africa (Burkina Faso). As Russia has been invested in different francophone African countries, an upcoming challenge is the potential redeployment of RT and Sputnik France in French-speaking Africa.

As ASD has observed, Russian talking points have also been laundered into the French media and political ecosystem through other vectors. While it is not surprising that the Russian Embassy in Paris has taken the baton from Russian state media outlets, the consistent presence of Russian propaganda in Chinese state media and diplomatic communications has been striking, though not surprising given Chinese messengers’ support for pro-Kremlin talking points about the war globally. Finally, the ability for Russian state media employees to appear in domestic French media outlets, typically with no indication of their past or current affiliation with Kremlin-funded outlets, points to yet another avenue for Russia to circumvent the EU’s ban and platform policies meant to restrict the spread of Kremlin propaganda.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.