Sooner or later harmful trends observed in the United States often take hold in Germany.

They might not be at the scale of what Americans confront, but the telltale signs are evident even in Germany’s strong democracy. That especially applies to elections, whether it be negative campaigning, a lack of substance about issues, or voter apathy; there are many similarities on both sides of the Atlantic. In 2016, foreign actors used cyber weapons and information manipulation to target the U.S. presidential election and cast doubt on integrity of the voting process. And in the 2020 presidential election, malign actors used influence operations to undermine confidence in the electoral process, denigrate certain candidates, and sow greater division within the electorate. This year Germany is a ripe target before and after the vote at the end of September. With the benefit of hindsight of what unfolded in the United States, Germany can take steps to further safeguard its election process.

For the first time since 1949, there is not an incumbent chancellor running, making the vote more significant not only for Germans but also for the country’s allies and adversaries. On top of that, the race is wide open and campaigning is laden with hot-button issues, such as the pandemic, gender, migration, and climate, which lend themselves to sowing mistrust and division within an electorate. Foreign and domestic players are seizing these topics and shaping online narratives to undermine trust and sway voters away from parties that stand in their way.

Russia has an outsized influence in Germany with the state-backed media outlet RT Deutsch. It is one of the top three media organizations in Germany when it comes to retweets. Not surprisingly the Greens candidate for chancellor, Annalena Baerbock, a vocal critic of Russia and the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, has attracted a disproportionate amount of negative attention on social media. In addition to attacking candidates, RT Deutsch spreads or generates content around certain positions on cultural issues to exacerbate sociopolitical divisions; for example, rainbow flags during the European soccer championship. It has also amplified controversies about the coronavirus to tarnish the credibility of the government and state institutions. According to the Alliance for Securing Democracy, “Impfpflicht” (compulsory vaccination) was the second-most used hashtag among Russian social media accounts in July.

Domestic actors have latched on to similar themes to erode support for the mainstream parties as well as the government. For example, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party has pushed misleading claims about vaccine mandates. Before the 2021 Baden-Württemberg state elections, it falsely alleged that the government’s COVID-19 contact-tracing app was being used for purposes other than infection tracking. Anti-vax communities and government skeptics have also been active in promoting conspiracy theories and questioning the efficacy of vaccines.

Against this backdrop of information manipulation, German voters should be alert to false election information and election officials should do their part to ensure a smooth vote. An election that does not go as planned is easier for malign actors to influence or interfere in.

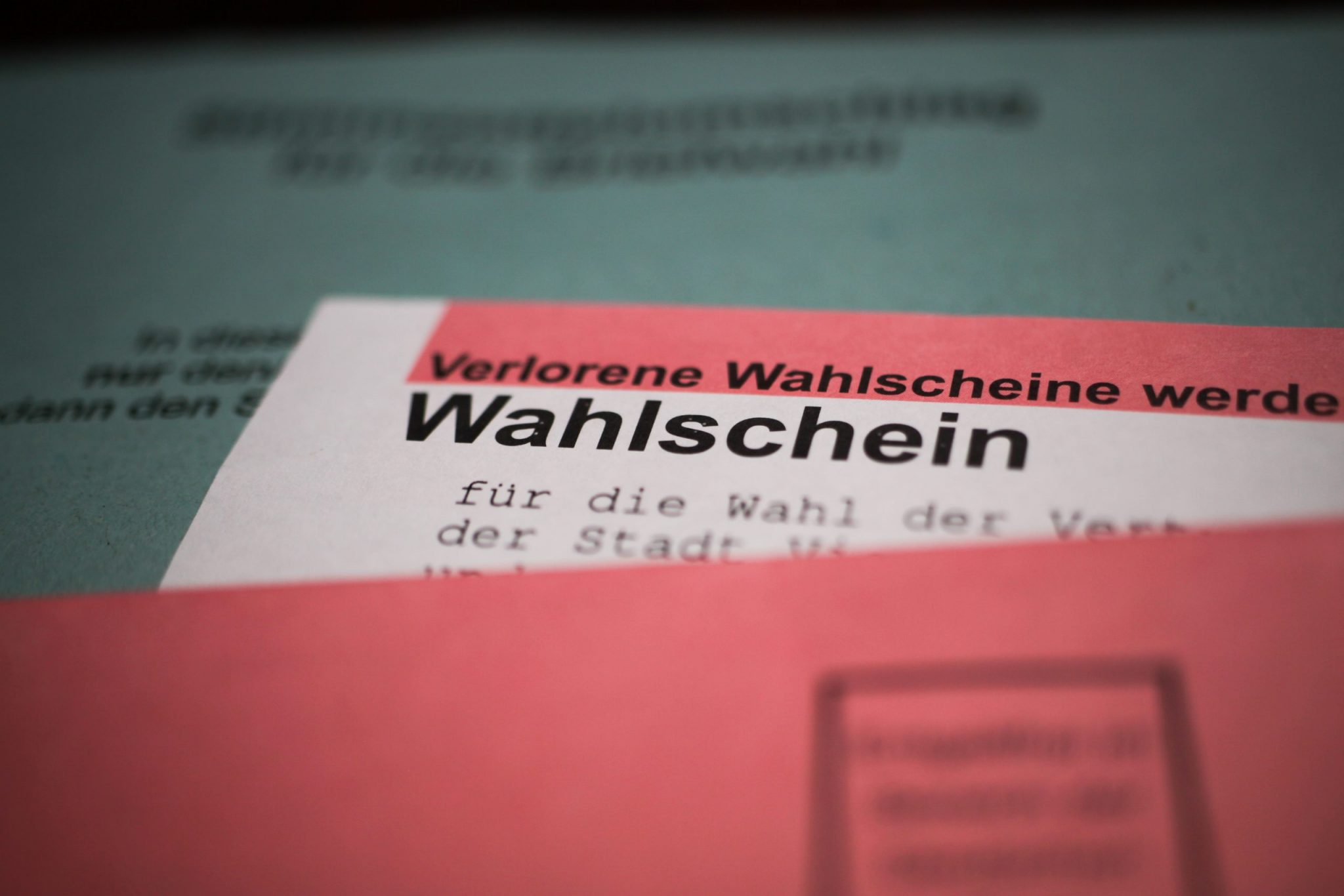

There is broad confidence in the integrity of Germany’s electoral process and the professionalism of its election administrators, but the conduct of the upcoming elections should not be taken for granted. In its Needs Assessment Mission Report, the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe reported some concern with how Germany will handle a potential increase in the number of requests for postal voting, due in part to the pandemic. Moreover, the AfD’s previous efforts to cast doubt on elections by spreading baseless allegations that mail-in ballots can be easily manipulated could resurface, a move that draws inspiration from Donald Trump’s campaign to discredit mail voting during the United States’ 2020 presidential election.

The good news is that German election officials have extensive experience with mail-in ballots. Almost 30 percent of the electorate voted by mail in 2017 and officials are aware of a potential surge for the upcoming federal election—mail-in ballots doubled during state elections this past year. Officials must continue informing voters about the processes and people that are in place to handle an unprecedented increase in mail ballots, while ensuring that all mandated voting methods are accessible to all voters. For their part, Germany’s voters should plan how they will vote well ahead of election day to help ensure that the voting process is as smooth as possible. Well-conducted voting is critical to the reality and the public perception of an election’s legitimacy.

Unlike in the run-up to the U.S. 2016 elections, it is not news to anyone that Germany is subject to information manipulation. A March report by the EU’s diplomatic service noted that Germany has been the main focus of Russian disinformation in the union. According to a Forsa poll 82 percent of Germans are anxious about information manipulation. If German citizens are not sure about the truthfulness of the content they are viewing, they should take steps to verify the information’s veracity. Although Germany has a well-financed public broadcasting system, growing skepticism, in part due to targeted attacks from foreign and domestic actors, about perceived bias has weakened its image. In addition to the established outlets, there are other tools, like the non-profit Correctiv, for fact-checking and verifying information that can be used to make an informed vote.

Finally, Germany should be prepared for more meddling. The adage of “after the election is before the election” also holds true for the post-September 26 period. Unlike certain parts of the United States that still use electronic-only voting machines, Germany only uses paper ballots. As a result, a successful election influence operation should not alter any election outcome because officials will have a paper trail to ensure that votes are properly counted. But with such a close race and an open question about the make-up of the next coalition government, forces within and outside the country will certainly continue to try to influence party agendas during coalition talks and engage in efforts to damage voter confidence in the government and democracy more broadly.

A shorter German-language version of this article was first published on September 2 by the Tagesspiegel and in Pioneer.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.