Overview

The aftermath of the U.S. presidential election has seen a tidal wave of false and misleading information about the validity of the election results as well as the legitimacy and security of the voting process. Narratives related to ballot fraud, voter suppression, and other allegations of electoral malfeasance have mushroomed across social and traditional media, casting doubt on the election even after Joe Biden was determined the winner. With few exceptions, these narratives have originated with domestic actors, most notably President Trump. Foreign state media therefore have served as amplifiers rather than creators of divisive election-related narratives, often by simply repeating or retweeting prominent American outlets or individuals. While Russian, Iranian, and Chinese state media have all used the political infighting to denigrate the United States and, by extension, liberal democracy, they have provided dramatically different coverage of the more spurious claims of widespread fraud. These differences speak both to their preferences for the two candidates, as well as their broader information strategy and geopolitical objectives.

By the Numbers

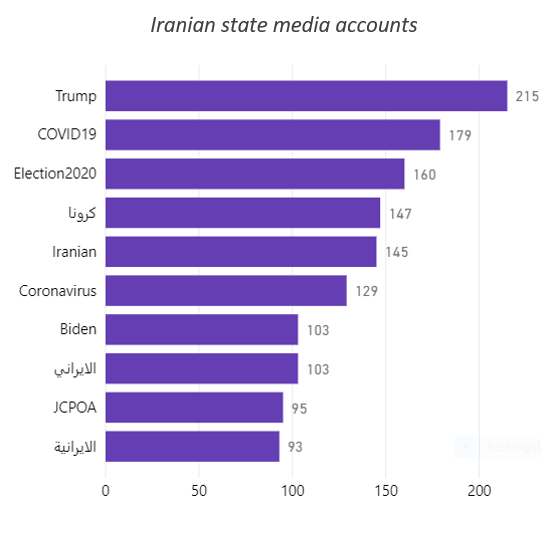

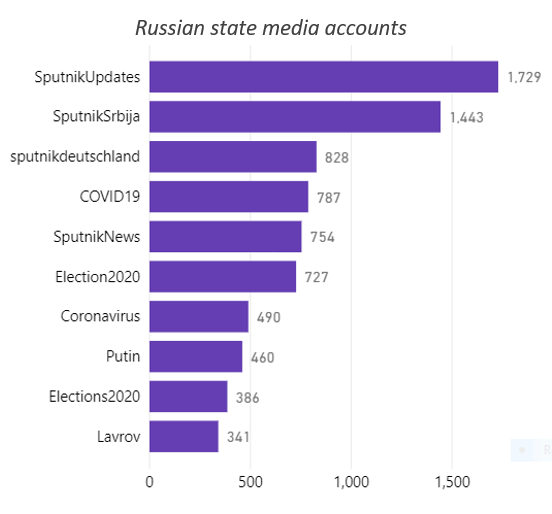

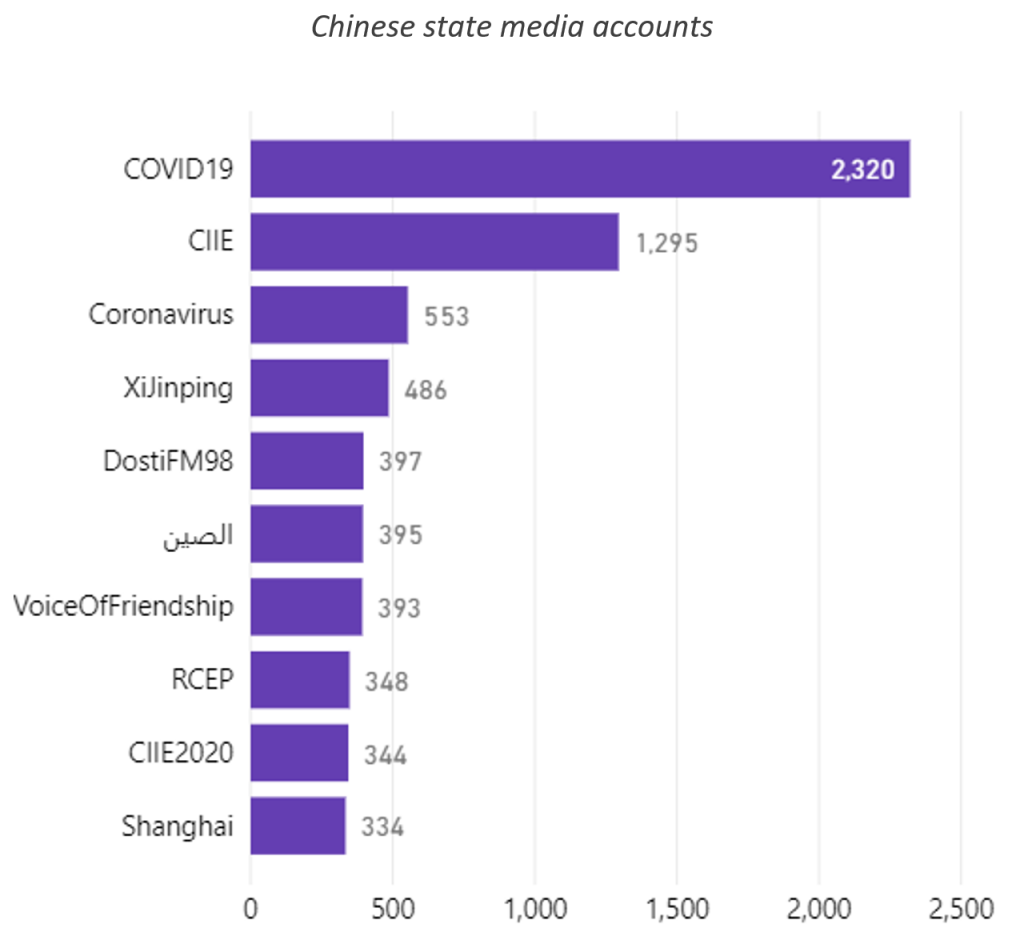

Between November 4 and November 18, the U.S. elections received substantial coverage from Russian and Iranian state media, with their respective Twitter outputs showing several election-related hashtags among the most-used by affiliated accounts. Chinese state media outlets, on the other hand, were unusually silent on the topic of the U.S. election, providing far less coverage (as a percentage of their total outputs) than their Iranian, Russian, and global media counterparts.

Top 10 Hashtags: November 4 – November 18, 2020

There were also stark differences in how the three countries covered general claims of voter fraud as well as more specific election-related conspiracy theories. Between November 4-November 18, the word “fraud” appeared in 224 tweets and 192 articles from Russian state media outlets or affiliated accounts; “rigged” appeared in 31 tweets and 19 articles; and the combination of “stop” and “steal” appeared in 19 tweets and 12 articles. By comparison, “fraud” appeared in 77 tweets and 34 articles from Chinese state media; “rigged” in 8 tweets and 3 articles; and “stop” and “steal” in 4 tweets and 3 articles. In Iranian state media outputs, “fraud” was mentioned in 82 tweets and 8 articles; “rigged” in 11 tweets and 3 articles; and “stop” and “steal” in 6 tweets and 2 articles. (Note: Some of the keywords were used in tweets/articles unrelated to the U.S. election, though all the associated top hashtags and keywords referenced persons or topics connected to the U.S. elections).

Although it is nearly impossible to track foreign state media’s amplification of the full range of vote-rigging conspiracies, analysis of specific keywords shows that Russian state media provided more coverage (and far less objective criticism) of “sharpiegate,” Dominion voting machine conspiracies, and allegations that absentee ballots were cast for dead voters, among other claims. In total, Russian state media outlets published at least 20 articles mentioning one of the aforementioned vote-rigging conspiracies, which was more than double the combined output of Chinese and Iranian state media outlets. While some articles refuted the claims, most did not. Many of the article repeated, unchallenged, claims by President Trump, his defenders, or right-wing media personalities.

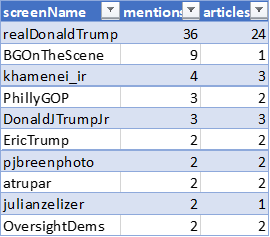

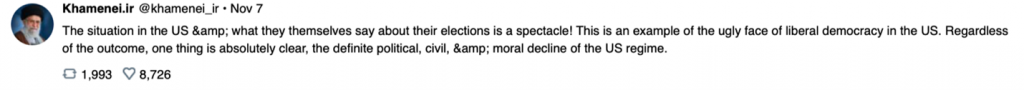

Perhaps most telling, embedded tweets in RT and Sputnik articles about the election mentioning “fraud,” “rigged,” or “steal” indicate a heavy reliance on President Trump’s Twitter feed to advance those claims. Between November 4 and November 16, 34 tweets from the president were embedded in 24 different RT and Sputnik articles amplifying voter fraud claims. The official Biden campaign account (@TeamJoe) was embedded in only one article, which was fewer than the president’s adult male children and the Supreme Leader of Iran (whose tweets criticized the president’s fraud claims as “the ugly face of liberal democracy”).

The top 10 embedded Twitter accounts in RT and Sputnik articles about voter fraud between November 4–November 16

For all three monitored countries, there were few instances of diplomats or government officials referencing the U.S. elections—either before or after the election. Combined, there were only 25 diplomatic tweets mentioning “fraud” in the context of the U.S. elections, the majority of which were Iranian embassy retweets of a tweet from the Supreme Leader characterizing the U.S. democratic process as irreparably broken.

Russian diplomats were unusually silent on the topic of the election, save for two of the more notorious troll accounts—the Russian Embassy in South Africa and Dmitry Polanski—who peddled standard Russophobia narratives.

What We’re Seeing on Hamilton 2.0

Russian, Chinese, and Iranian amplification (or lack thereof) of U.S. election fraud claims not only reflect broad differences in the information strategies of the three countries but also their preferences for the two U.S. presidential candidates.

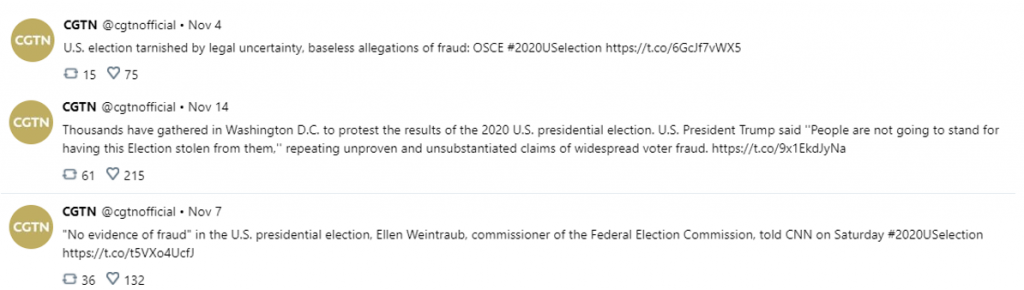

To date, China’s state media outlets have given the smallest platform to vote-rigging allegations and, when covered, have generally added disclaimers and caveats indicating that the claims are “unproven,” “unsubstantiated,” or “baseless.” This is consistent with coverage in other international media outlets.

Examples of Chinese state media outputs covering U.S. election fraud claims

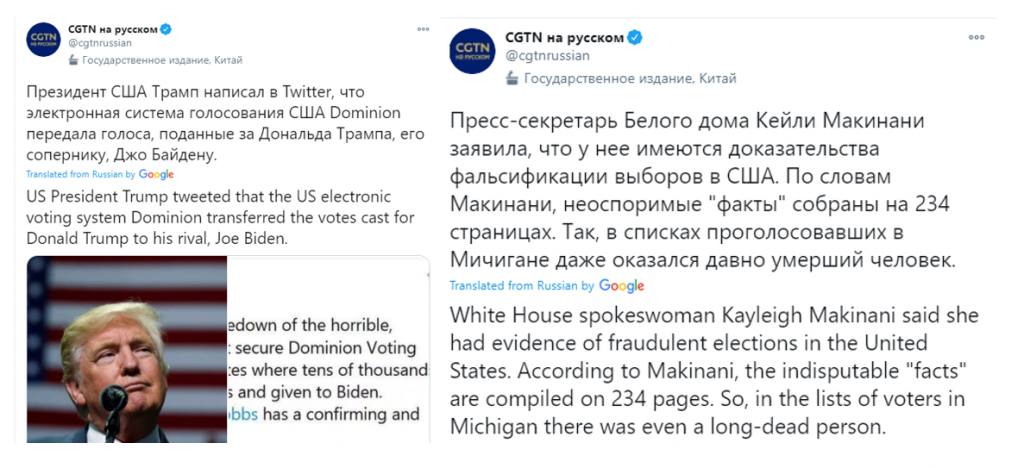

Coincidentally or otherwise, the exception to that rule has been China’s coverage of the U.S. elections in CGTN’s Russian-language outlet, which has provided less skeptical coverage of the Trump administration’s vote-rigging claims.

CGTN’s Russian-language amplification of voter fraud conspiracy theories

That Chinese state media coverage has largely refrained from breathlessly promoting unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud is typical of their comparatively more restrained coverage of internal political issues in the United States (and other countries). It also, perhaps, speaks to their generally more critical coverage of President Trump, who is seen as the primary promoter of voter fraud allegations.

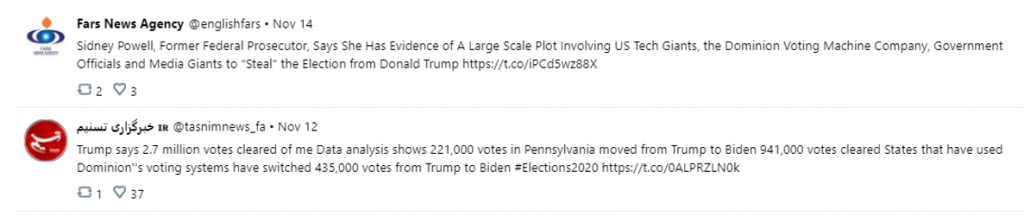

By contrast, Iranian media outlets and diplomats repeated domestic claims of Dominion voting machine and other conspiracies, often eschewing journalistic best practices for reporting on unsubstantiated allegations.

Iranian state media mentions of the conspiracy theories related to Dominion voting machines

At the same time, opinion pieces in Iranian state media did not attempt to legitimize fraud allegations but instead used them to attack the American political system. The intent, therefore, seems to be aimed less at undermining U.S. faith in the reliability of electoral processes and more at undermining the appeal of democracy and pax Americana.

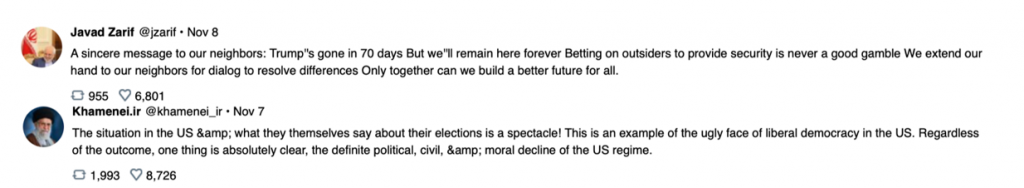

Iranian diplomatic coverage of the aftermath of the U.S. presidential elections

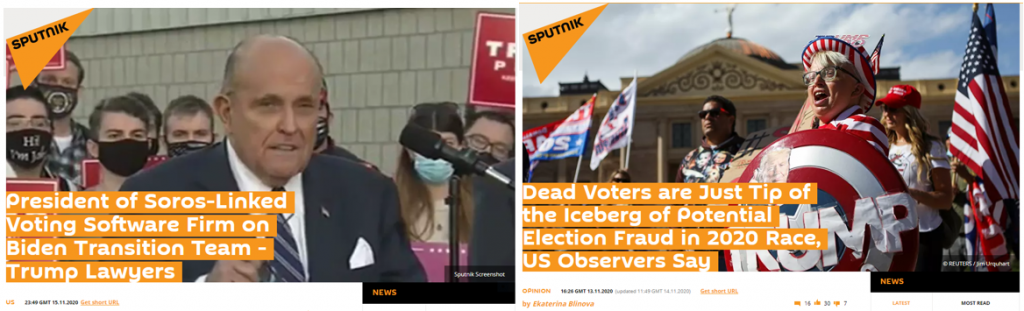

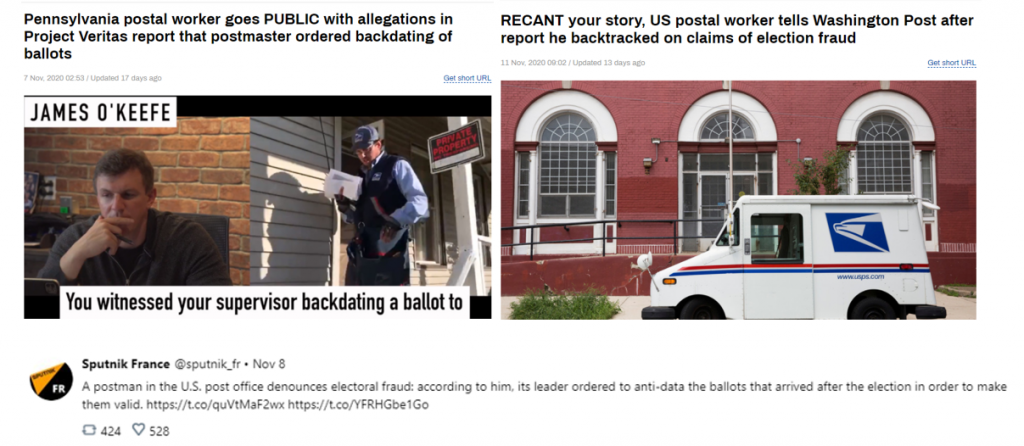

Unsurprisingly, Russian state media has provided the most credulous coverage of voter fraud allegations. Although Russian state media has provided some skeptical coverage of the more outlandish claims, there has been a consistent pattern of elevating and amplifying fraud claims, often without critical assessment. Beyond amplification of the president’s tweets, RT has published five different articles promoting Project Veritas videos alleging postal fraud, a narrative that RT and Sputnik consistently promoted in the run-up to November. When the source of those claims recanted, RT—echoing Project Veritas—alleged that the postal worker recanted under pressure.

Russian coverage of allegations of mail-in ballot fraud in the U.S. election

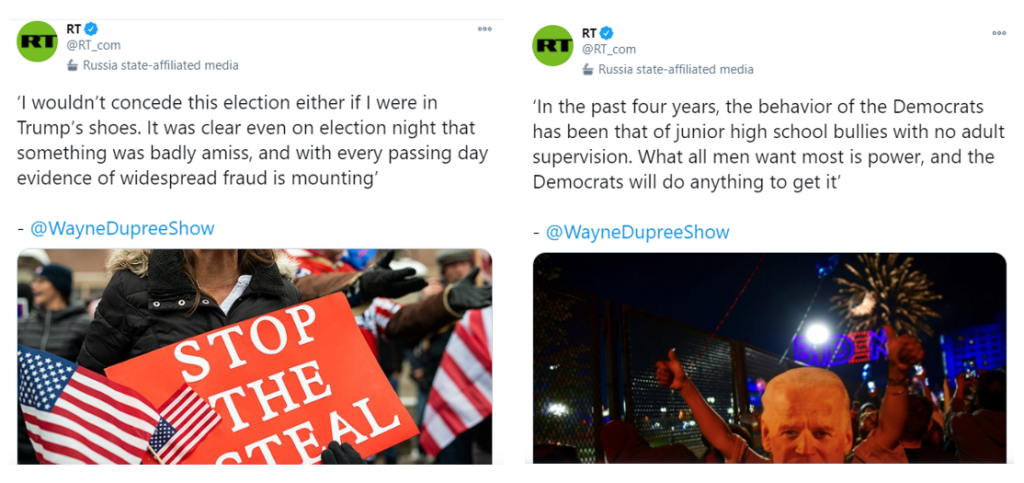

Beyond amplifying Project Veritas, there has also been increased synergy between Russian media outlets and U.S. “conservative” outlets in the aftermath of the election. Sputnik radio ran a segment with the Gateway Pundit’s Jim Hoft, and Wayne Dupree, who on his Parler account called for starting a “civil war” rather than allow “these liberal pieces of crap to win by stealing the election,” has been one of the most prominent contributors to RT over the past month. This convergence is notable, as before the election RT and Sputnik’s content was often aimed at progressive rather than conservative audiences.

Examples of Wayne Dupree’s opinion pieces in Russian state media

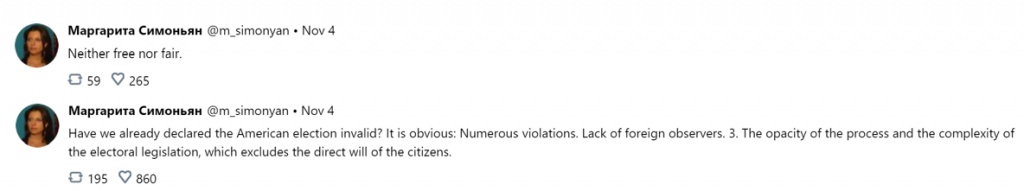

While the three monitored countries provided very different coverage of election fraud narratives, the common thread in Russian, Chinese, and Iranian post-election messaging has been a clear sense of schadenfreude at the decline of U.S. democracy. Russian state media, for example, suggested that election chaos is evidence that there is “no exceptionalism or grandeur in American democracy,” that “U.S. democracy really is in its death throes,” and that the political system “needs to be retired.” RT Editor-in-Chief Margarita Simonyan also provided several none-too-subtle digs at the U.S. electoral process, using the United States’ prior criticisms of unfair election in other countries.

Similarly, Iranian state media and diplomatic accounts have consistently used the Trump administration’s fraud allegations to belittle U.S. attempts to promote democracy abroad. While alleged U.S. hypocrisy is a regular feature in Iranian messaging, the messy post-election period has led Iranian leaders to claim that the election has revealed the “real face” of the United States.

As an interesting aside, Iranian outlets relied on “U.S. analysts” Caleb Maupin and Jim Jatras, who both happen to be mainstays on RT, to validate its case—further evidence of the cross-pollination between adversarial state media outlets.

Iranian state media content about election fraud featuring two prominent RT analysts, Jim Jatras and Caleb Maupin

While more diplomatic in its coverage, China’s state media editors—often the sharper edge of China’s messaging spear—also leveraged post-election unrest to paint an unflattering image of the United States. Additionally, they did not refrain from taking a few pointed parting shots at President Trump and his cabinet.

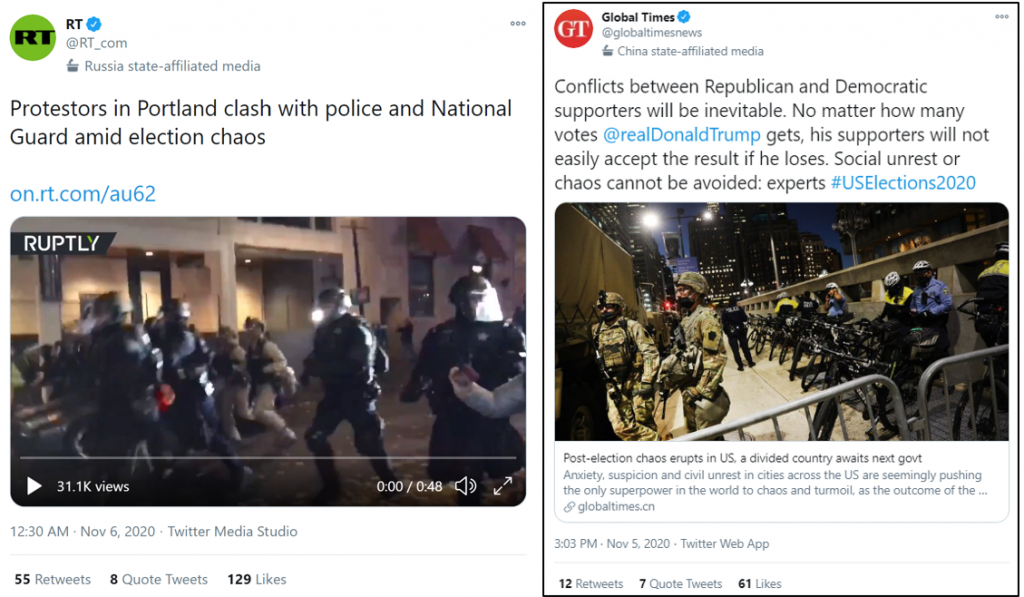

Finally, the three countries have provided significant coverage of unrest and sporadic violence in the United States. Again, this follows a pattern of depicting and often exaggerating the supposed decline of U.S. society, though the specific coverage of post-election unrest has largely been factually accurate.

Examples of Iranian, Chinese, and Russian state media coverage of post-election violence and protests

Why It Matters

Russian, Chinese, and Iranian messaging about claims of widespread voter fraud in the 2020 U.S. presidential elections shows the extent to which divisive and partisan infighting in the United States has been used to damage the United States’ brand. Additionally, content analysis shows that the specific narratives and conspiracy theories used by state media outlets to sow distrust in the U.S. political system almost exclusively originated from domestic voices. This is hardly a new trend; Russia has long relied on partisan outlets and commentators as their sources for divisive content. The difference, however, is that the most damaging narratives have not been sourced from the fringes of the political spectrum—although those too received some airtime—but from our own political leaders, especially the president.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.