Since the earliest days of the pandemic, Chinese state officials and media outlets have disseminated conspiracy narratives claiming that COVID-19 originated at Fort Detrick—a U.S. army research facility in Maryland that has been the target of disinformation campaigns for more than four decades. But Chinese efforts to pump conspiracy narratives about the lab into the information bloodstream have accelerated in recent months in response the Biden administration’s renewed interest in the possibility that the virus leaked from China’s Wuhan Institute of Virology. According to data collected on ASD’s Hamilton 2.0 dashboard, Chinese government officials and state media outlets have posted more than 1,000 tweets, articles, and videos about Fort Detrick since May, flooding social media platforms with elaborate conspiracy theories that have been thoroughly debunked—and thus largely ignored—by credible media outlets.

The amplification of conspiracy theories by Chinese state media and officials is not in itself remarkable, and Fort Detrick is far from Beijing’s only target of disinformation narratives about the origins of the virus. What is remarkable about the Fort Detrick narratives is their foothold in powerful, influential places: search engines.

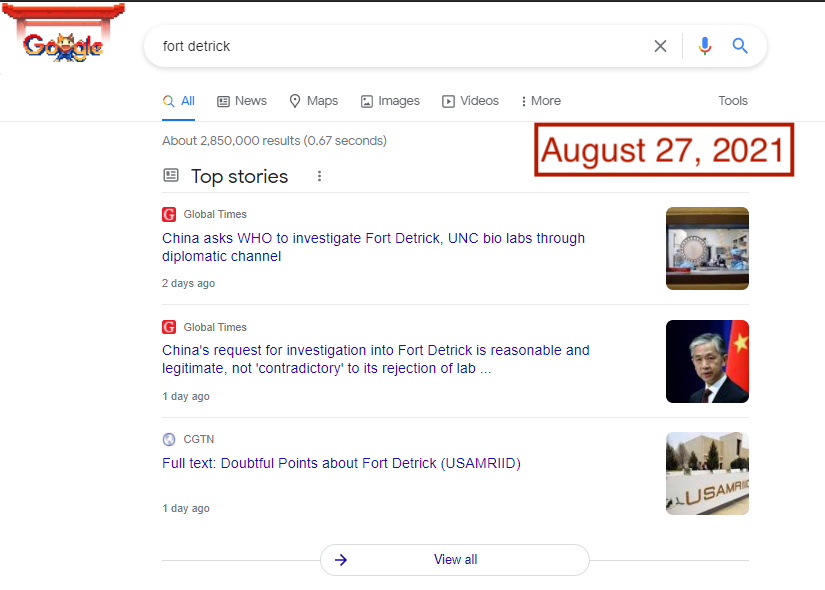

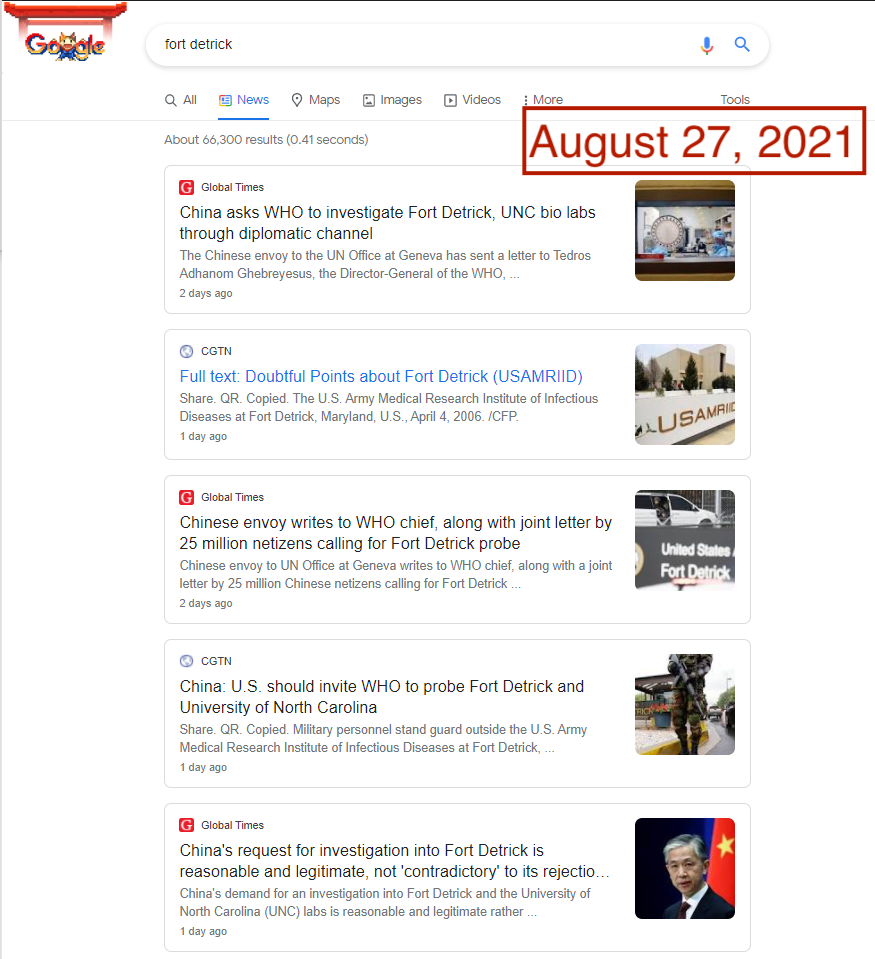

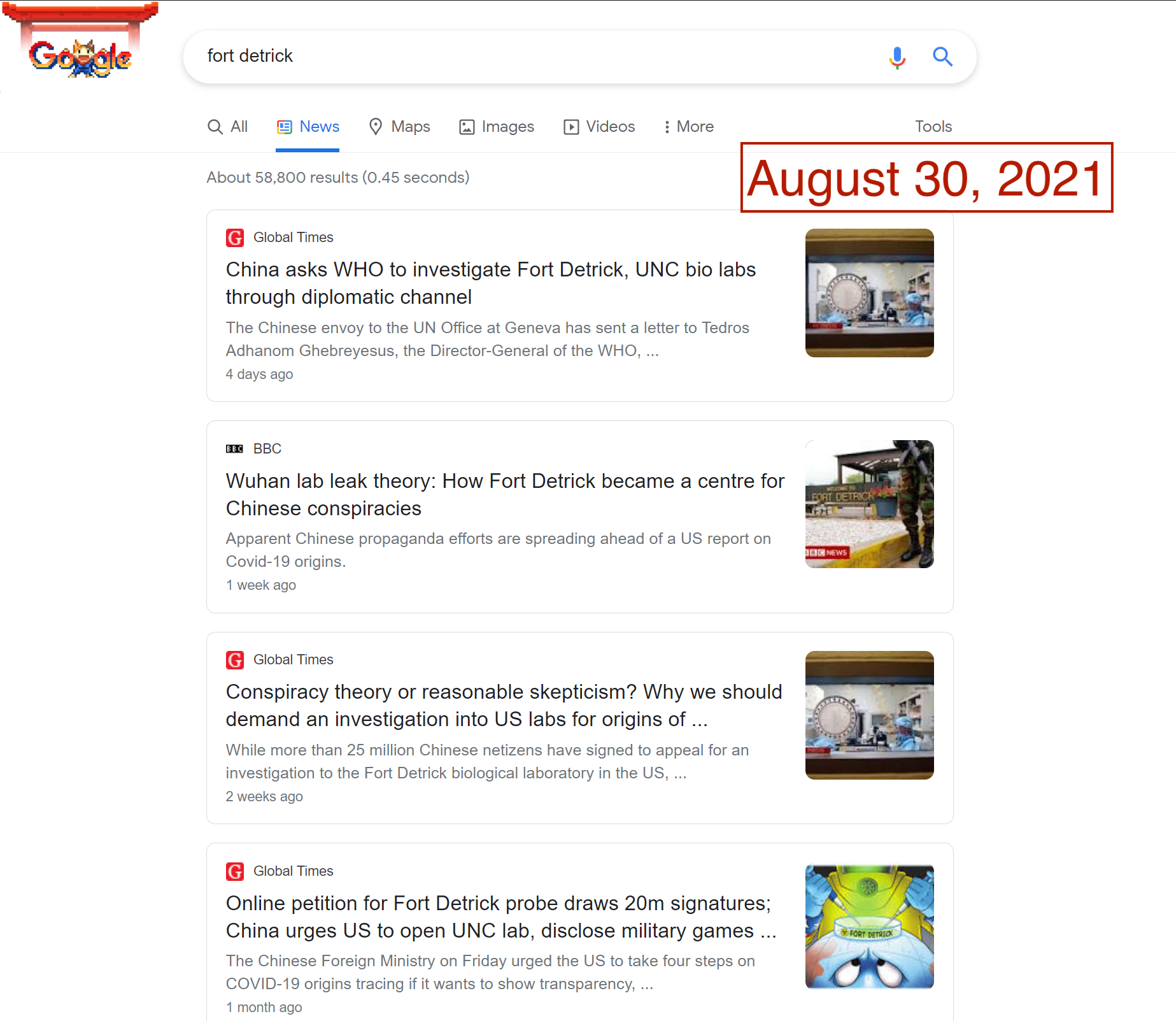

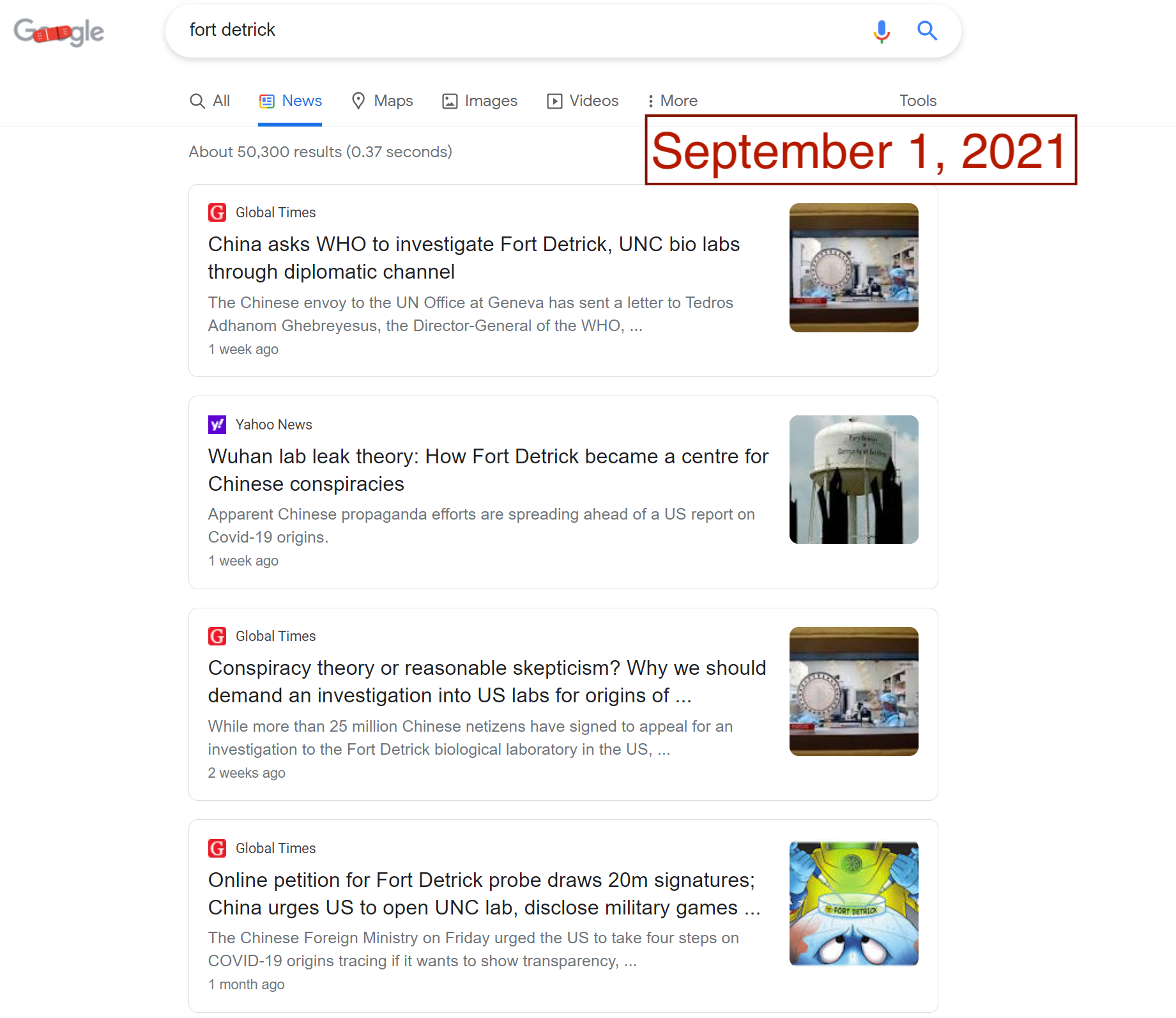

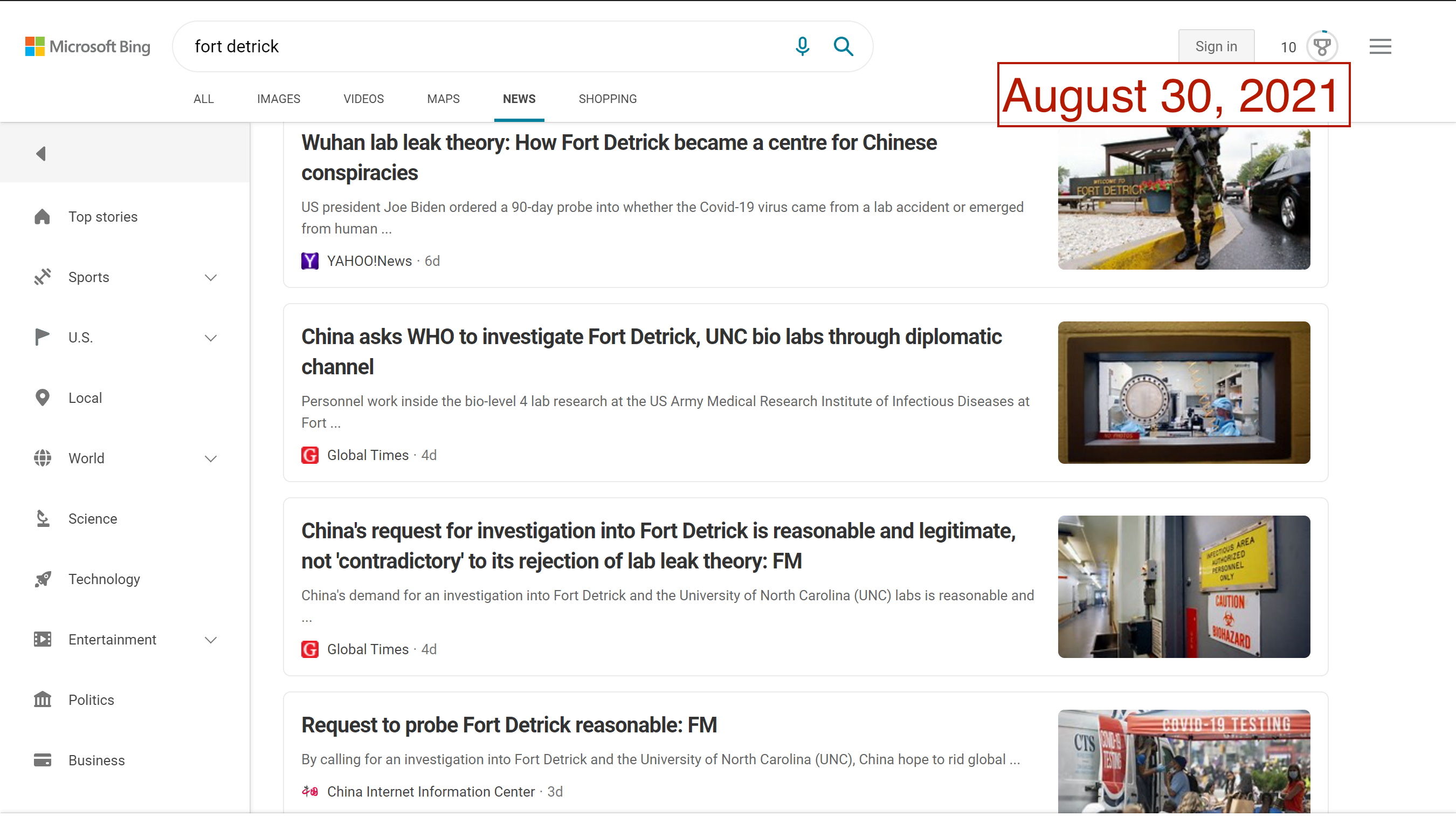

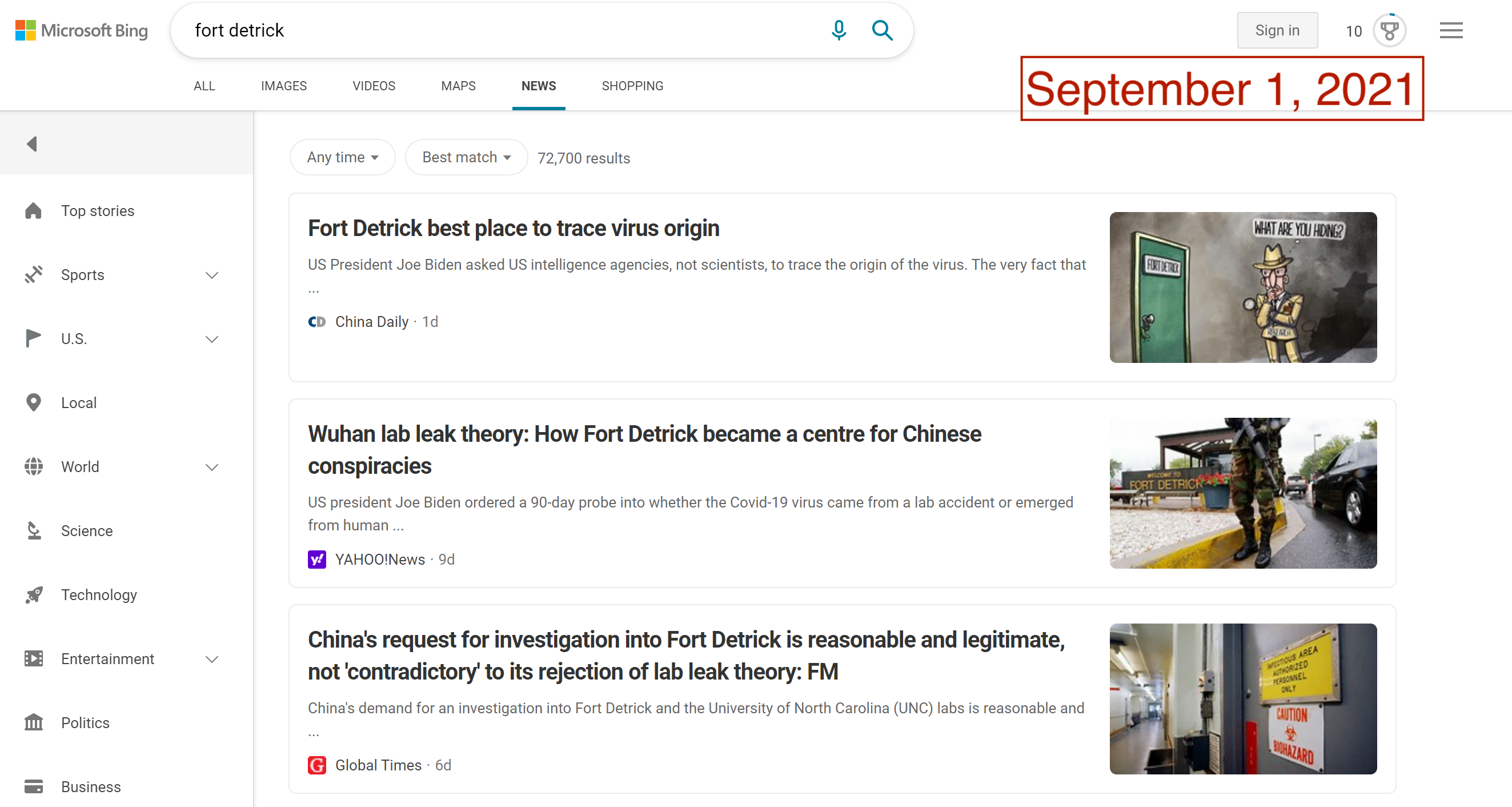

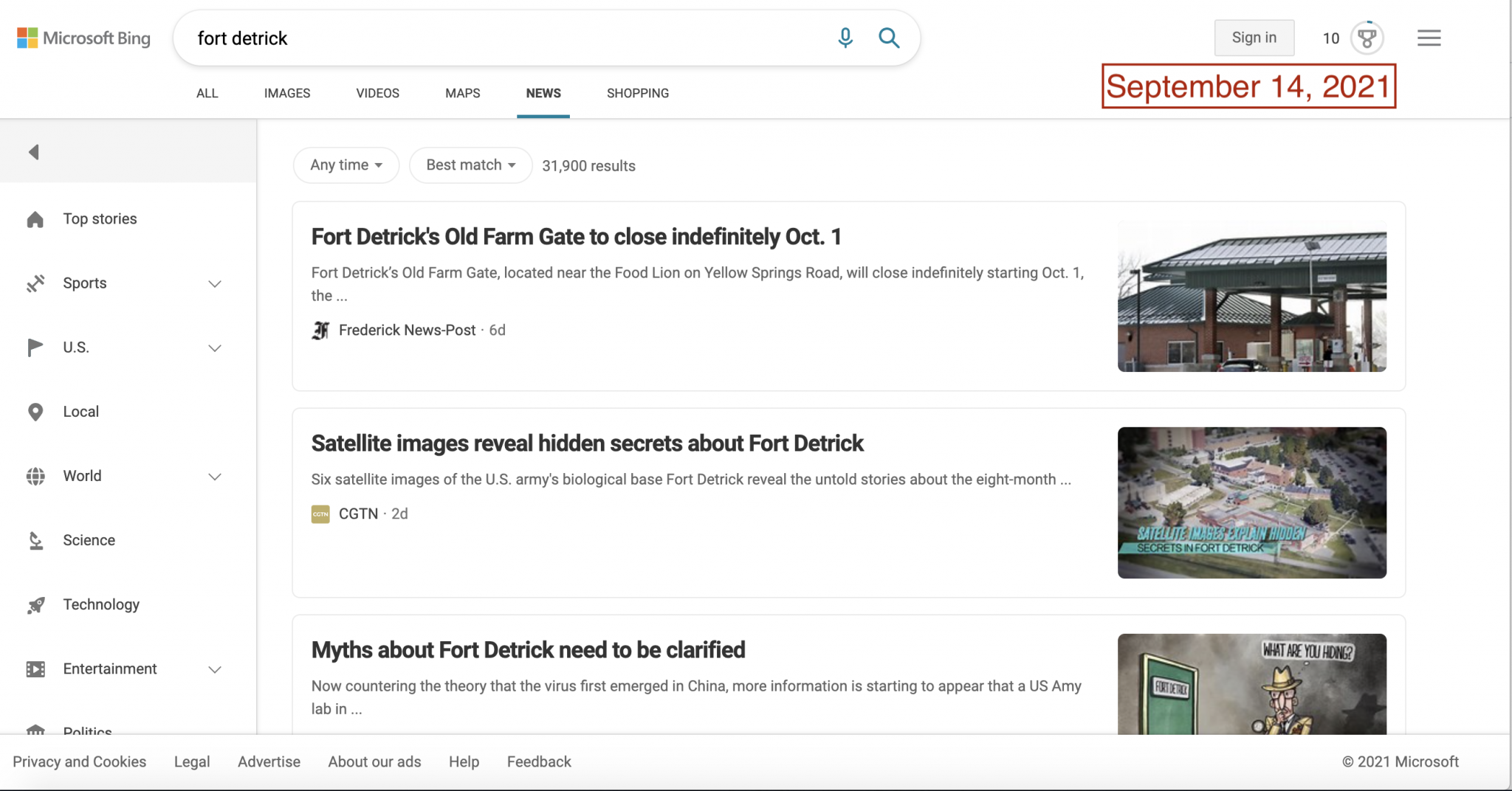

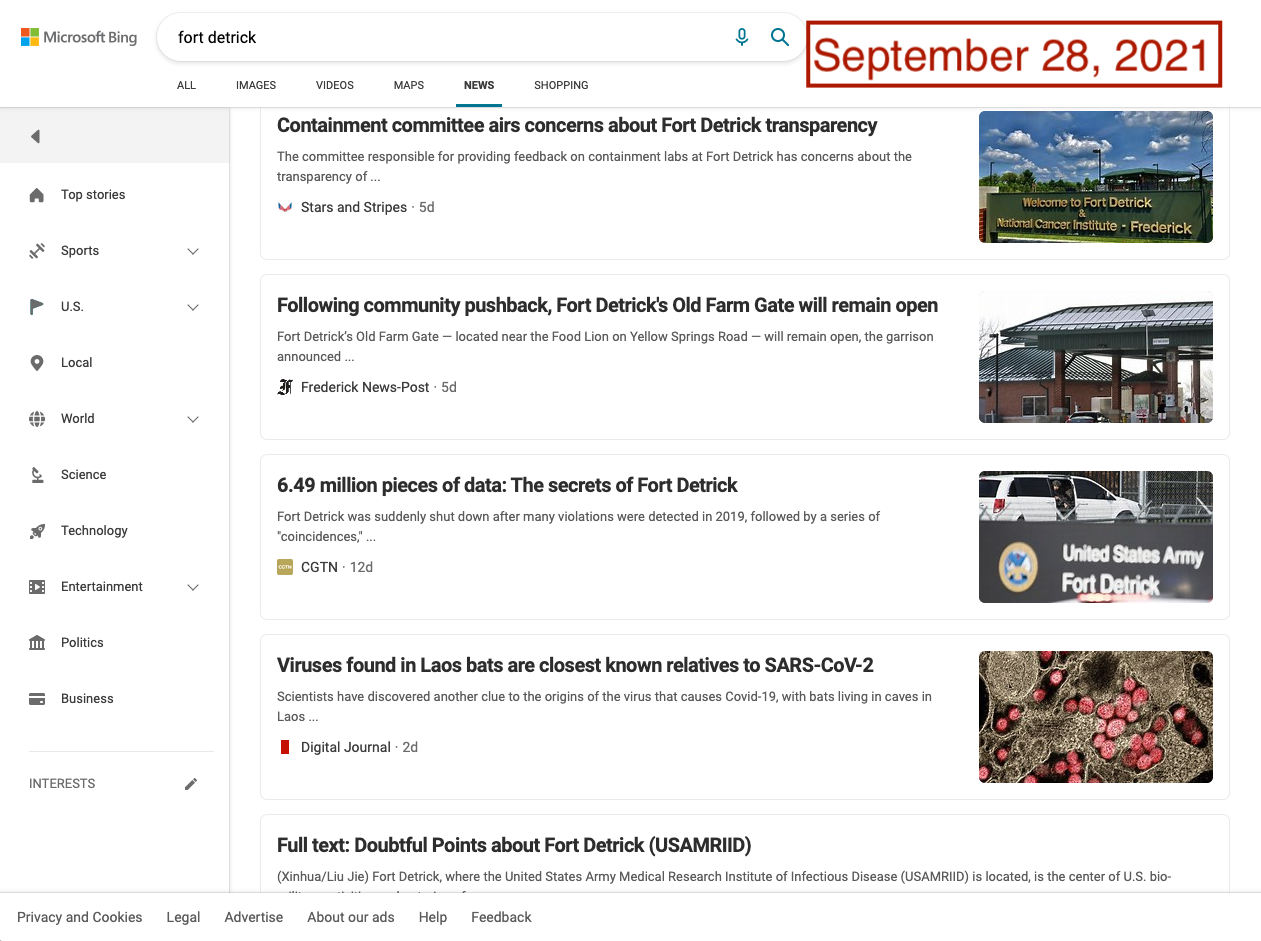

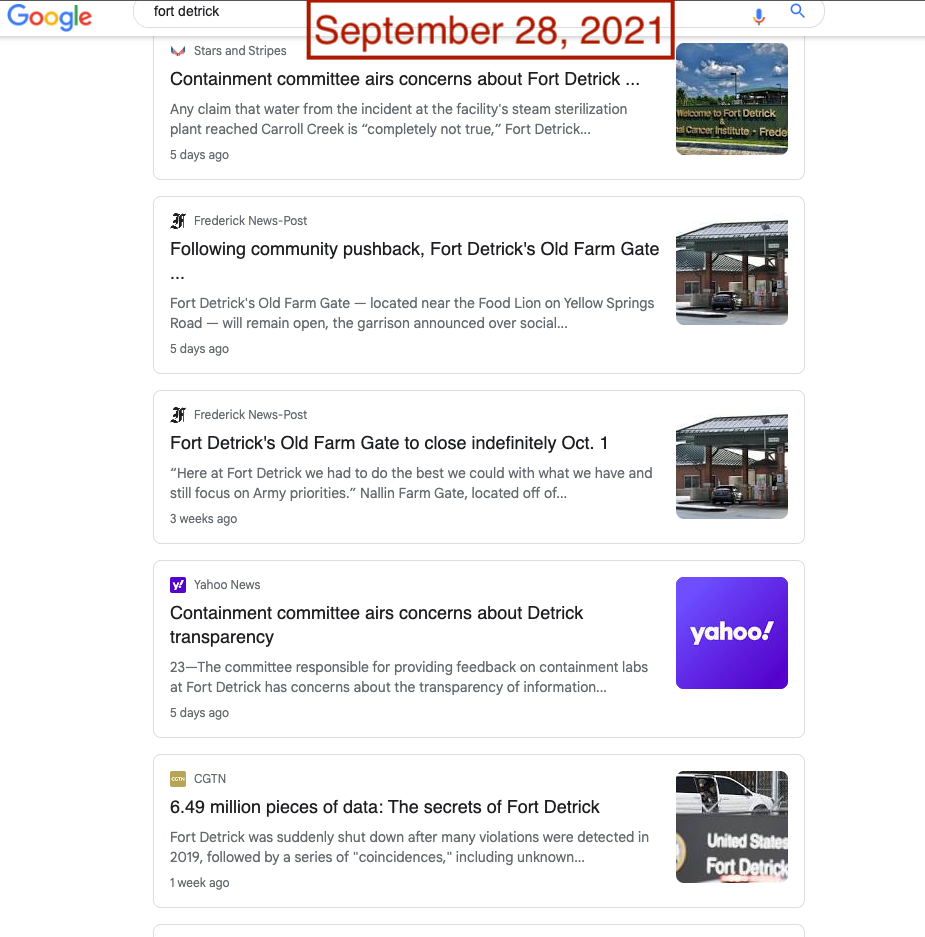

For people encountering the world of Fort Detrick conspiracies for the first time, turning to a search engine would be a common step in the search for information. Unfortunately, popular search engines could lead consumers directly to the very sources of Fort Detrick conspiracy theories. In August and September, Google News results for “Fort Detrick” were dominated by CGTN and the Global Times, two Chinese state-run outlets that are central to Beijing’s information operations. In late August, the frequency and volume of misleading stories about Fort Detrick reached enough of a peak to also dominate Google’s Top Stories feature. Searches on Bing News have not fared much better, with Global Times and China Daily appearing in top results.

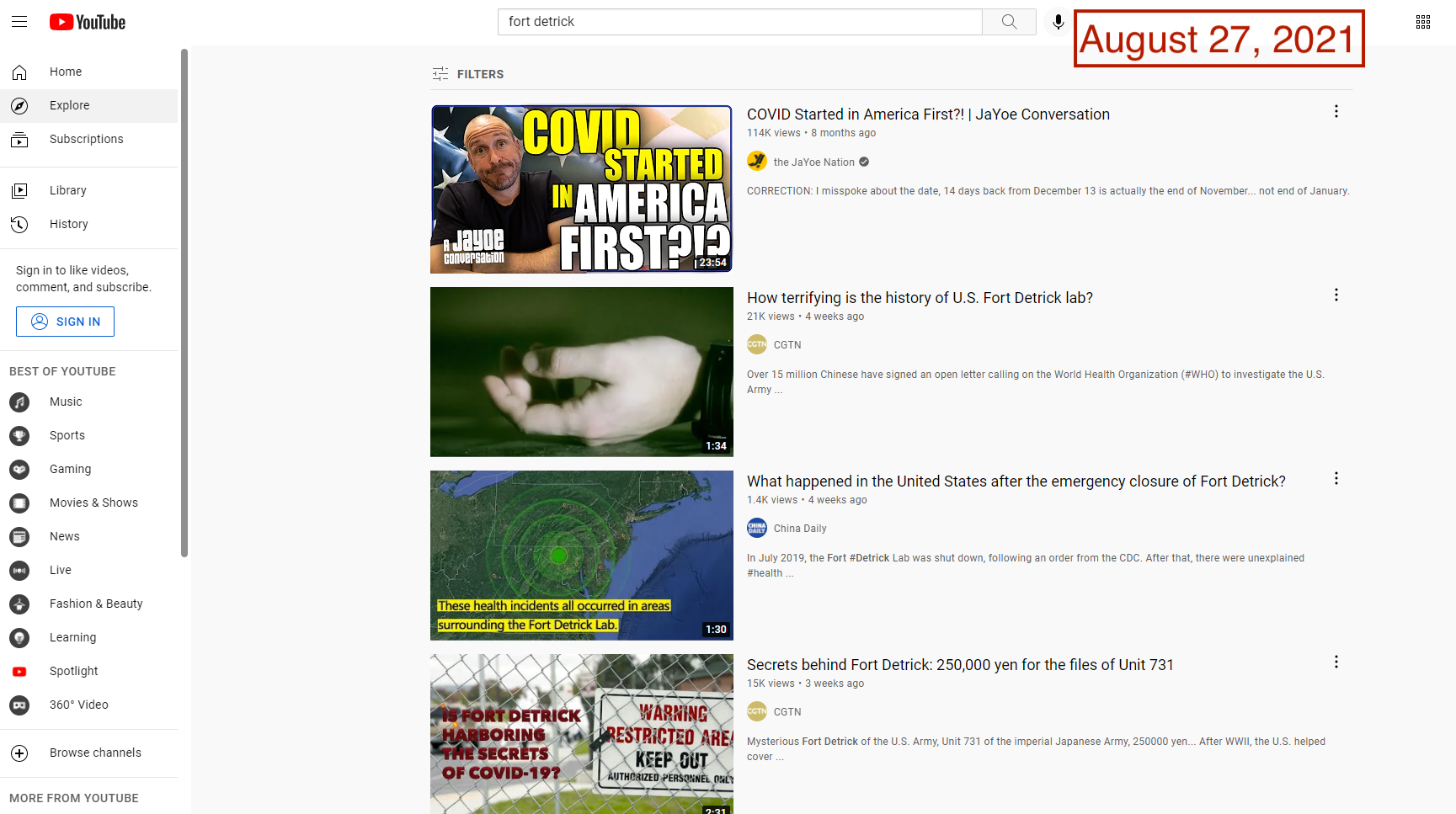

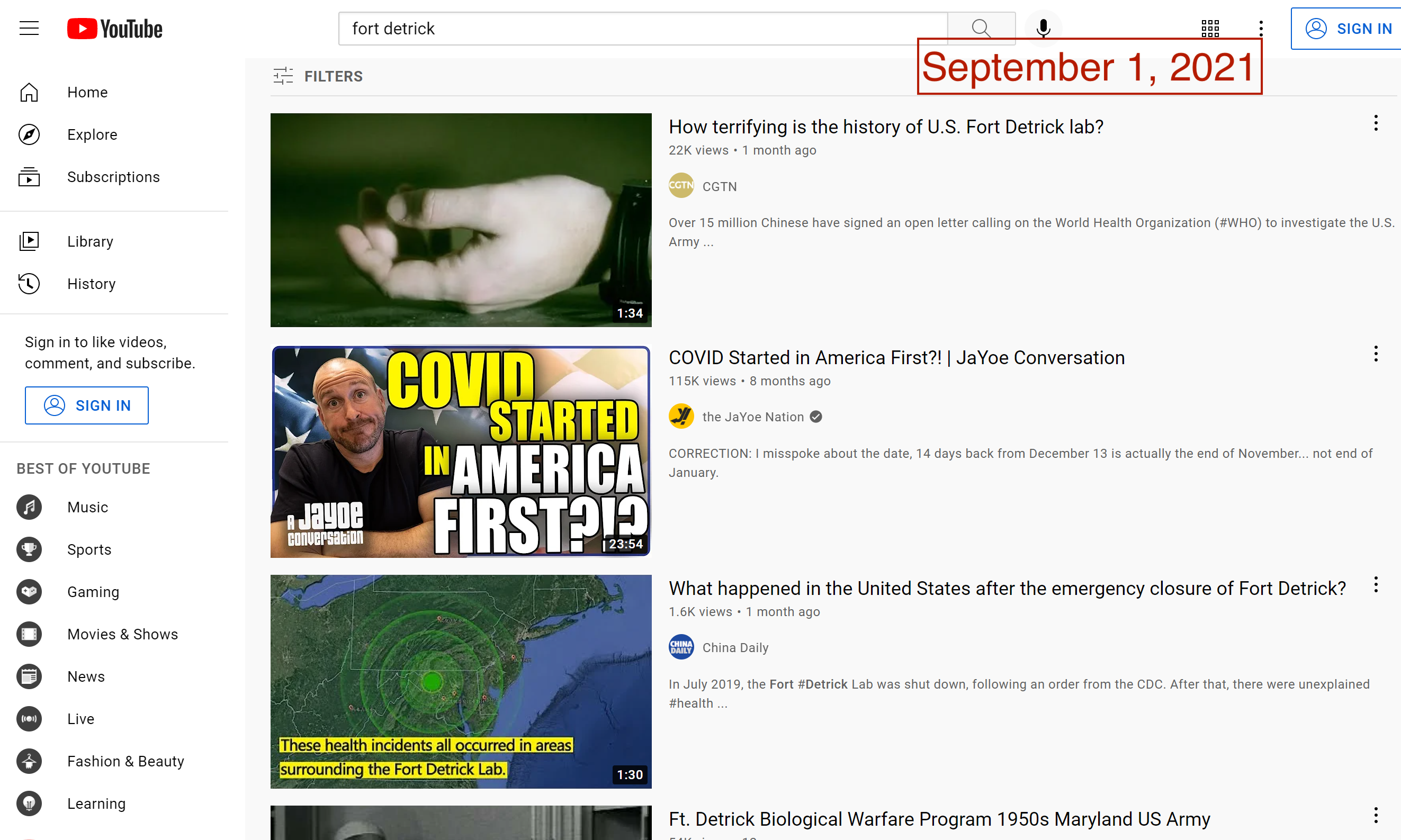

And on YouTube, four of the six top videos returned in a recent query for “Fort Detrick” were from Chinese state media channels. The other two results promoted Beijing-friendly talking points.

Data Voids and Propaganda

These results are a perfect example of what researchers danah boyd and Michael Golebiewski call data voids—situations where search terms lead to limited, nonexistent, or deeply problematic information. In a 2019 paper that analyzed the concept, boyd and Golebiewski explained that data voids emerge “when obscure search queries have few results associated with them, making them ripe for exploitation by media manipulators with ideological, economic, or political agendas.” Data voids can occur naturally or through intentional manipulation, and are products of multiple factors, including information availability and the inner logic of search engines. (Understanding search engine optimization, for example, can allow malicious actors to construct problematic content around a particular term.) The paper also identified several major types of data voids. One example is a breaking news data void, which occurs when a rapidly changing news event leads to scarce or low-quality results. This void is likely to be filled over time as journalists produce more content that search engines can index. Data voids can also occur through more targeted and long-term manipulation; individuals can generate problematic information about a term to the point of dominating the corresponding search results, and then amplify public curiosity about the term to lead users to the results. As boyd and Golebiewski explain, the term “crisis actor” became the focus of such manipulation in the aftermath of the 2012 mass shooting at Sandy Hook as conspiracy theorists generated content alleging that children and parents had been paid to act as victims of the massacre. Six years later, after a horrific shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, the concept of crisis actors entered mainstream discourse, and people who searched the term encountered “a strategically optimized information ecosystem” that had been constructed for years.

As an example of a low-quality news situation, Fort Detrick highlights a few additional aspects of data voids. First, the years-long flow of disinformation narratives surrounding the term “Fort Detrick” highlights the hybrid approaches that information manipulators can take in exploiting data voids. The first seed of the Fort Detrick disinformation campaign was planted in March 2020, when Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian retweeted a since-deleted article from Global Research Canada, a conspiracy site with links to Russian disinformation operations, that suggested a link between the lab and the global outbreak. This opening salvo was quickly countered by quality reporting debunking Zhao’s claim, thus preventing a breaking news data void. But over the course of the year, as Chinese state media outlets and government officials continued to generate content about Fort Detrick, search results were increasingly dominated by Chinese disinformation narratives, as evidenced by Google trends results indicating that the most common search query related to “Fort Detrick” in 2020 was “Fort Detrick coronavirus.” Therefore, when China doubled down on Fort Detrick disinformation in May, they encountered an information environment saturated with their own narratives and a western media less interested in covering a topic that had already been thoroughly debunked.

This points to a second vulnerability manipulators exploit. While there is a first-mover advantage to filling a data void, search engines are built to prioritize the “freshest” or most recent content—thus advantaging actors who not only publish early but often. Information manipulators can therefore exploit the media’s fleeting attention span or, in the case of conspiracy narratives, their responsible impulse to not amplify far-fetched rumors, even in an attempt to supplant them with truth. When credible outlets did cover the Fort Detrick rumor, as was the case in August when BBC News published analysis of the disinformation campaign, the story gained a top spot in Google and Bing search results. However, one reliable story cannot fill a data void, nor can it neutralize its dangers for news consumers. As Chinese state outlets continue to publish a steady stream of conspiratorial articles about Fort Detrick, their content again dominates news results, exploiting search engines’ emphasis on freshness.

The freshness dimension of search results can also fragment data voids in other ways. In late September, some local news from Fort Detrick—about a wastewater flooding incident and the closure of a town gate—made the top of the first page of Google News and Bing News results, overtaking older CGTN and Global Times conspiratorial articles. Chinese state media outlets nevertheless kept their foothold on the first page of both engines, and if the emphasis on fresh content persists, a new wave of content from the Chinese state propaganda machine could easily dominate results again. Bing News results for “Fort Detrick” on September 28 betrayed another vulnerability that can be exploited to spread poor-quality information. On this day, the fifth news result was a MSN link that contained a republication of a Xinhua News Agency piece about Fort Detrick based on a Chinese diplomat’s assessment of Fort Detrick’s ties to COVID-19. The news aggregator often hosts Xinhua content, and in this instance, the hosted content was part of a state-driven propaganda campaign with dire public health risks. This example hints that merely de-ranking websites would not be a complete solution to data voids;even if a state propaganda outlet were de-ranked, its news aggregator contracts would still provide an avenue for gaming search engine results.

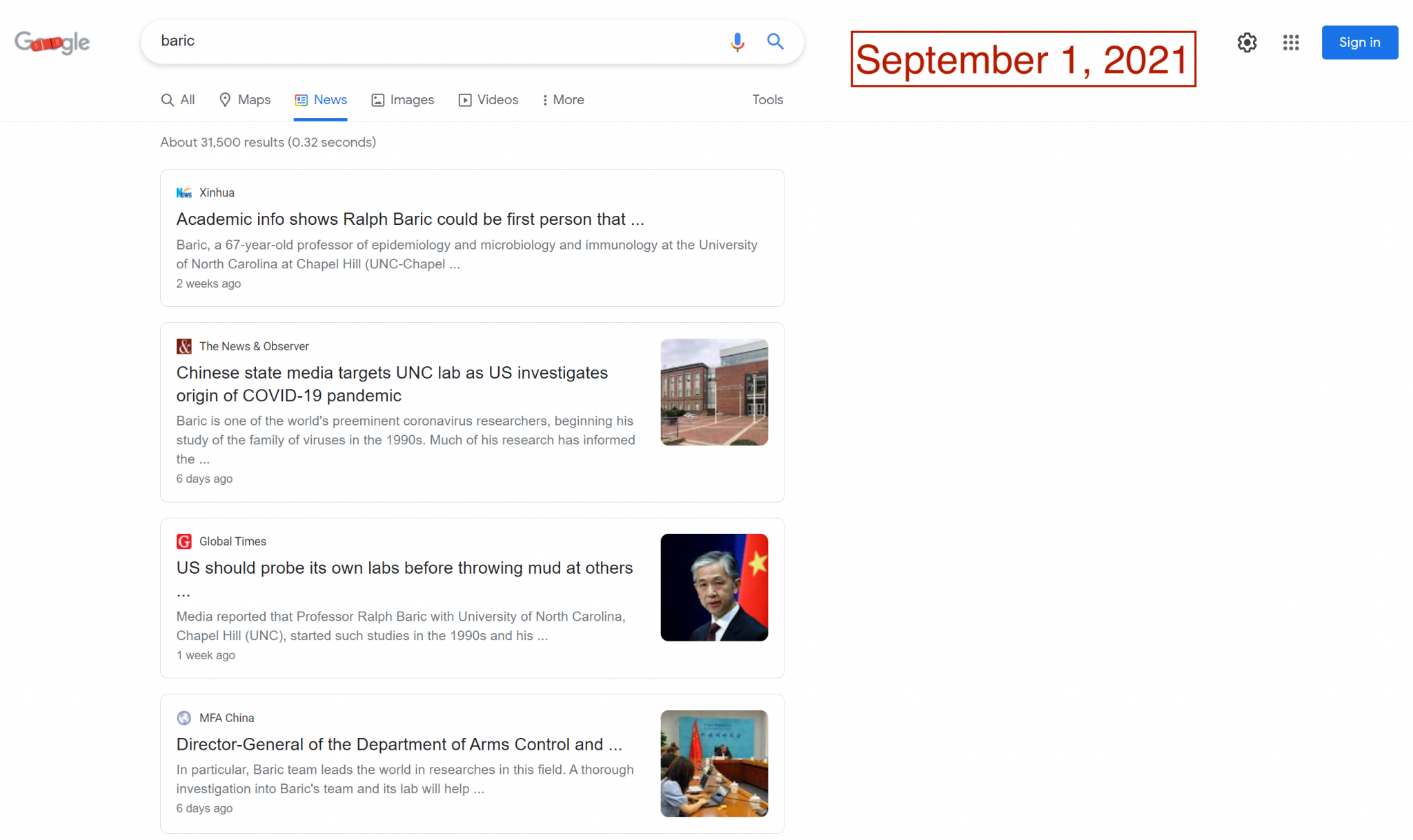

Third, the narratives surrounding Fort Detrick show that manipulation of data voids can be multidimensional, hinging not just on single search terms but a cluster of related ones. For example, one narrative strand has tried to implicate University of North Carolina professor and epidemiologist Ralph Baric in the creation of the coronavirus. Another has suggested a link between Fort Detrick and an outbreak of EVALI (e-cigarette or vaping use-associated lung injury) that occurred in 2019 in Wisconsin. Searching for news about “Baric” or “EVALI” on Google and Bing leads to results dominated by the Global Times, China Daily, and Xinhua, all related to Fort Detrick and the origins of COVID-19. These individual terms form a network of data voids, each reinforcing the problematic ideas of the other.

Finally, China’s ability to marshal its global propaganda apparatus to shape the Fort Detrick search environment highlights an asymmetric advantage autocratic state actors enjoy in the information domain. Unlike democratic media ecosystems, whose outlets are by design less responsive to the wishes of the state and more responsive to the capricious interests of the public, autocratic governments can direct state-sponsored information channels to repeatedly target high value search terms with preferential narratives. This has created an environment where state media outlets can effectively own sensitive or strategically important search terms, as was previously noted in a 2018 blogpost by former ASD Program Manager Bradley Hanlon, who exposed the ubiquity of Kremlin-funded media in Google Top Stories results for terms such as Nord Steam, MH17, and Sergei Skripal.

Is There a Data Voids Defense?

The potential harm stemming from these information ecosystems cannot be overstated. As long as manipulated information continues to simmer within these data voids, the consequences for public health and awareness will grow. Skepticism of COVID-19 vaccines, mask mandates, and other public health measures is hardening in communities around the world, and these narratives around Fort Detrick serve to unsettle people about the origins and gravity of the virus. More broadly, if contested geopolitical topics can be dominated by a single state—including democratic ones—historical records, at least online, may be subject to rampant manipulation.

Since the publication of boyd and Golebiewski’s analysis of data voids, which began in 2018, researchers have built on their work to expand our understanding of data voids, the risks they pose, and how we can confront them. First Draft and the University of Sheffield, for example, have introduced the related concept of data deficits, situations defined by high demand for information about a topic and a low supply of credible information, to highlight mismatches in the information supply chain. Researchers at Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center have launched a project to analyze and measure the lifespans and harms of data voids. Other scholars have pointed to the vulnerabilities of users to data voids emerging from the search functions of social media platforms, and to the role of language in differentiating a void from a wealth of credible information. Search engines are also showing awareness of the problem. In June 2021, Google unrolled a notice for search results that are rapidly changing and may not contain reliable sources—a move that may curb the risks of breaking news data voids. Google has also expanded the regional availability of its Questions Hub, a tool that identifies content gaps (including by asking users what questions they were unable to answer through search) and helps coordinate efforts to fill them.

As scholars and technologists pay more attention to the issue of data voids, efforts to fill voids with credible information should be accompanied by efforts to better understand how malicious actors exploit them in the first place. As the Fort Detrick example shows, data voids can move beyond search terms to encapsulate entire topics, and the presence of credible news does not always neutralize the dominance of manipulated stories.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.