On February 4, 2022, Russia and China surprised many observers by releasing a joint statement promising a “no limits” friendship, which they described as “superior to political and military alliances of the Cold War era.” Just after the Beijing Olympics ended several weeks later, Russia invaded Ukraine. Leaders in China reportedly expected a quick Russian victory that would strengthen Russia, divide Europe, and distract the United States. Instead, the opposite occurred. Putin’s reckless invasion has weakened Russia, united Europe, and refocused the United States on confronting authoritarianism. From a strategic perspective, Russia’s invasion appears to be a disaster for both Moscow and Beijing.

It might, therefore, have seemed logical for Chinese leaders to tone down their rhetorical support for Putin in recent weeks. After all, China has frequently highlighted principles that are hard to square with Russia’s invasion, including “mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit and peaceful coexistence.” And key democracies’ accelerating counter-balancing against both Russia and China is not in Beijing’s interests. Indeed, some Chinese scholars have privately suggested that Chinese leaders are trying to adjust their rhetorical support of Putin for exactly these reasons.

As we explain below, however, Chinese state media appears to be doubling down on Russian messaging and disinformation, based on data from our War in Ukraine and Hamilton 2.0 dashboards. Through a variety of information channels, Beijing is framing the conflict on Putin’s terms, promoting pro-Kremlin narratives, and embracing Russian disinformation campaigns, including falsely suggesting that the United States is funding biological weapons laboratories in Ukraine. This bodes ill not only for China’s relationship with the United States, but also for its ties with Europe. American and European experts are increasingly questioning whether it is possible to make progress with China on issues related to international security. In this sense, China’s response to Russia’s invasion is seen a litmus test—and Beijing is failing. China’s rhetorical support for Russia could therefore have far-reaching consequences for the prospects for cooperation among many of the world’s leading players in the years ahead.

Framing the Conflict on Russia’s Terms

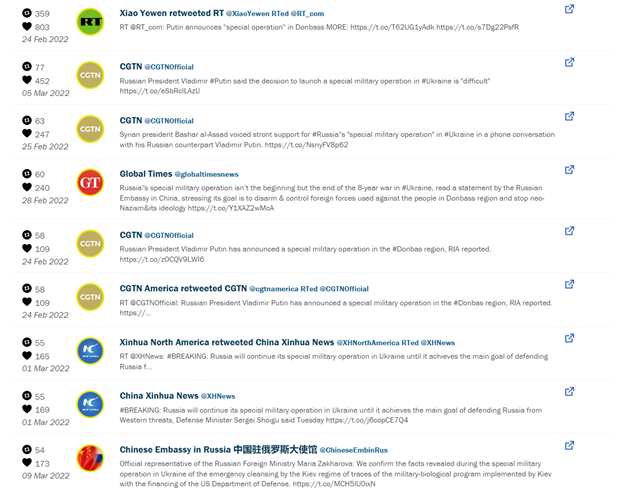

Chinese state media and government officials have largely adopted Kremlin-mandated sanitized language used by Russian media to describe the war in Ukraine. Since Russia’s invasion began on February 24, Chinese government officials and state media have used the term “special military operation” far more often than the term “invasion” to describe Russia’s actions. On Twitter, for example, monitored official Chinese accounts mentioned the terms “special operation” or “special military operation” 180 times between February 24 and March 12. The word “invasion” was mentioned 145 times during the same period—though more than a third of those mentions promoted whataboutism narratives related to previous U.S. invasions, most notably Iraq.

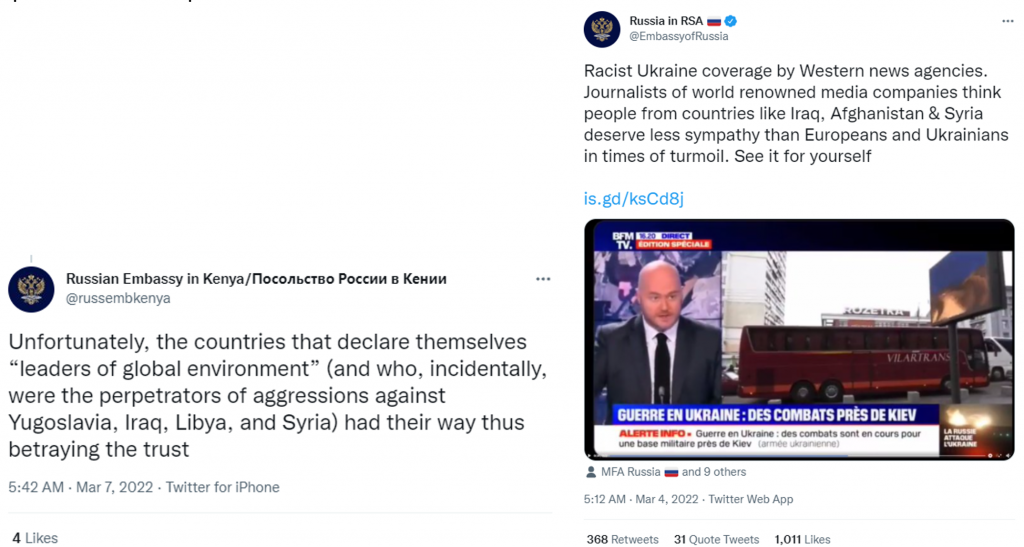

Examples of Chinese diplomatic accounts referring to past U.S. invasions in the context of the war in Ukraine.

Chinese officials and state media have been more than twice as likely to use the term “special operation” rather than “invasion” when not focusing on past U.S. operations. The term special operation is occasionally presented in quotes by diplomats and Chinese state media—suggesting the use of language from a third party, in this case, Russian officials or state media. Often, however, the term is presented without quotation marks, pointing to an editorial decision to use Kremlin-friendly phrasing.

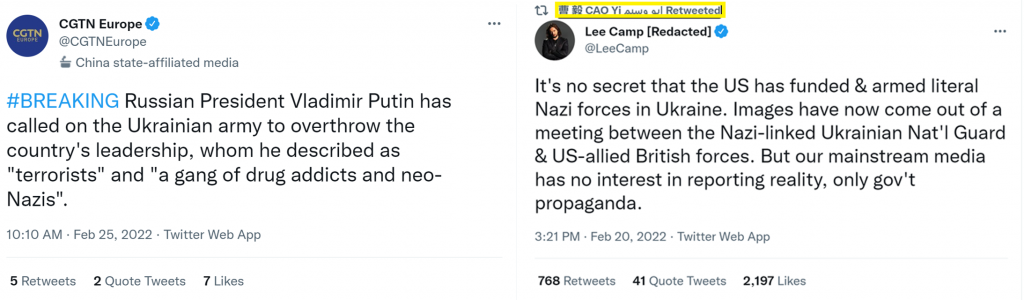

The most retweeted tweets from accounts monitored on Hamilton 2.0 adopting the Kremlin-preferred term “special operation” to describe the war in Ukraine between February 24 and March 12, 2022. Note that the most retweeted tweet is a retweet of Russian state media outlet RT by the Deputy Consul General of China in Auckland Xiao Yewen.

Chinese diplomats have been especially averse to using the terms “invasion” or “war” to describe Russian aggression in Ukraine. Between February 24 and March 12, Chinese diplomatic and government accounts used the term “war” (134 mentions in original tweets) almost exclusively to describe past U.S. wars, the Cold War, or war in a more general sense, preferring more neutral terms like the Ukraine “issue” (345 mentions) or “situation” (252 mentions). Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Hua Chunying addressed the issue directly by claiming that the use of the word “invasion” represents a double standard. She suggested, incorrectly, that the Western media avoided the term when describing U.S. military actions in Afghanistan and Iraq.

CGTN’s coverage of Hua Chunying’s objection to the use of the term “invasion” and MFA spokesperson Zhao Lijian’s linguistic gymnastics to blame “Uncle Sam” for the war, while also referring to the war as a “crisis.”

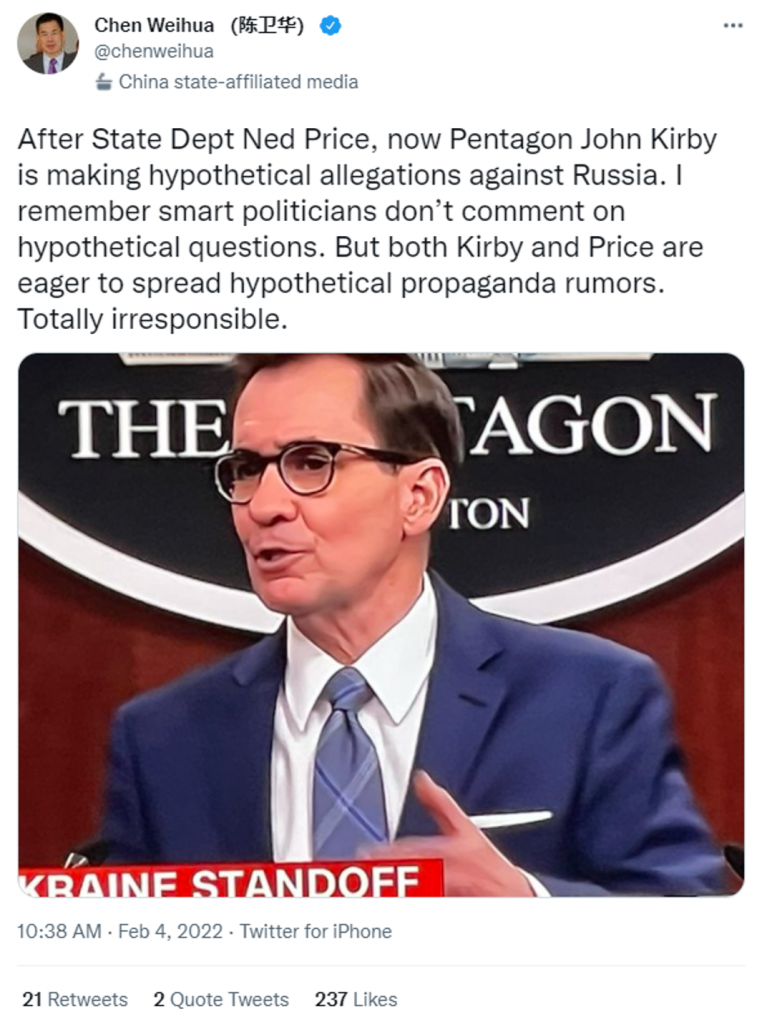

Chinese state media has also extensively quoted, retweeted, and paraphrased statements made by Russian government officials and Russian state media outlets both before and after the invasion. This included amplifying the now-obvious Russian disinformation campaign prior to the invasion that a potential war in Ukraine was Western media “propaganda” and “information hysteria.” Conversely, U.S. government warnings of a potential false flag operation conducted by Russia as a pretext for war were almost entirely ignored, except to ridicule U.S. government officials for “making hypothetical allegations.”

ABOVE: Examples of Chinese state media outlet CGTN promoting statements from Russian government officials in early February suggesting that Western warnings of an imminent war were “propaganda” and “information hysteria.” BELOW: The EU bureau chief of China Daily mocking U.S. government spokespeople for what proved to be correct predictions about Russian actions in Ukraine.

Unverified information and claims sourced from Russian government officials, including Russian President Vladimir Putin, are also frequently presented verbatim without appropriate journalistic caveats. This includes Putin’s unsubstantiated accusation that “Ukrainian neo-Nazis opened fire on Chinese students,” an allegation that even China’s foreign ministry declined to confirm. Chinese state media outlet Frontline—not to be confused with the PBS docu-series of the same name—also ran allegations from Russia’s Ministry of Defense that the Ukrainian “Nazi military is torturing the Russian military.” The accusation went uncontested by state media.

Chinese state media outlet CGTN Africa and Frontline broadcasting uncontested allegations made by Russian government officials about Ukrainian atrocities, including attacks on Chinese civilians.

Promotion of Pro-Kremlin Narratives

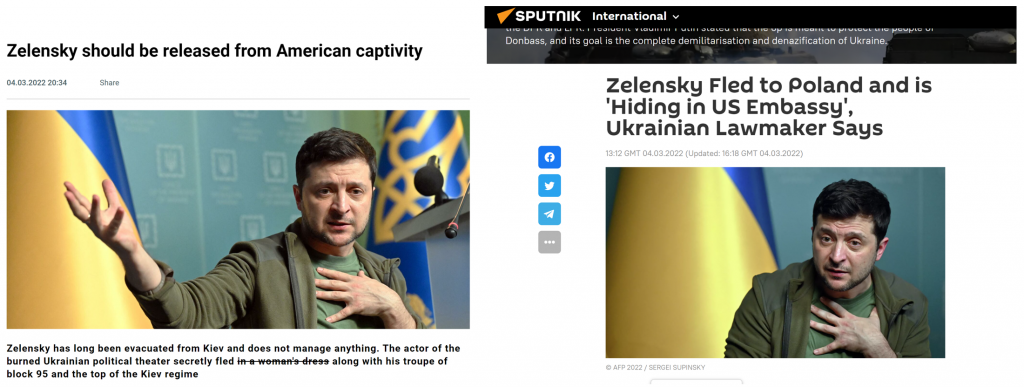

China has actively promoted the key narratives and talking points used by the Kremlin to justify its war in Ukraine. By far the most prominent theme in China’s editorialized coverage of the war has been the advancement of anti-U.S. and anti-NATO narratives. This has taken the form of extensive whataboutism—namely efforts to call out Western hypocrisy and double standards related to U.S.-led wars over the past three decades—as well as efforts to defend Russia’s “legitimate security concerns” related to NATO enlargement and alleged U.S. aggression. China has also portrayed the West as a weak and unreliable partner, a message that could speak to Chinese interests vis-à-vis Taiwan. China’s messengers have even shown a wiliness to boost Kremlin narratives unrelated to China’s interests, such as exaggerated claims about neo-Nazi influences in Ukraine and the Russian-driven conspiracy theory that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky is in hiding at the U.S. Embassy in Poland.

ABOVE: Russian intelligence-linked disinformation site NewsFront and state media website Sputnik claimed that Ukrainian President Zelensky is, respectively, being held by the CIA or “hiding in the US Embassy in Poland.” BELOW: The false claim of Zelensky hiding in Poland promoted by China’s Consul General in Belfast, Zhang Meifang, who retweeted the conspiracy theory posted by a pro-Beijing account, @PandemicTruther.

Whaboutism and Accusations of Western Hypocrisy

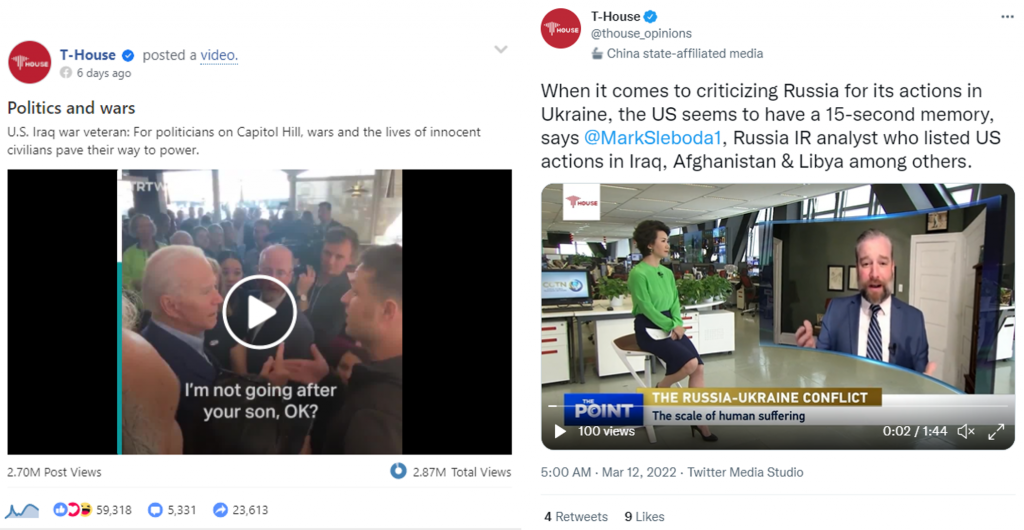

China and Russia often redirect blame for their human rights abuses by calling out the failings of their accusers, namely the United States. In the context of the war in Ukraine, both Russia and China have repeatedly made counteraccusations related to U.S. and European involvement in wars in Serbia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen. Between February 1 and March 12, 2022, Chinese diplomatic and state media accounts made hundreds of posts on Facebook and Twitter referencing those wars and attacking the alleged hypocrisy and double standards in Western governments’ responses to and Western media’s coverage of the war in Ukraine. On Facebook, for example, a post made in early March by CGTN affiliate T-House showing an Iraq war veteran confronting U.S. President Joe Biden received 2.7 million views. The outlet also hosted frequent RT and Sputnik contributor, Mark Sleboda, to advance similar double standard narratives.

Examples of Chinese state-affiliated media outlet T-House using whataboutism tactics to shift the focus from Ukraine to past U.S. wars.

China’s diplomatic “wolf warriors” and the ministry of foreign affairs have also frequently promoted these counternarratives. These messages often have mirrored those pushed by the Kremlin and Russian diplomats over the past two weeks.

ABOVE: Examples of Russian diplomatic accounts making whataboutism and double standard arguments. BELOW: Those same arguments advanced by Chinese diplomats in Lebanon and Russia.

Framing the U.S. and NATO as Aggressors and Unreliable Partners

Russian diplomats and state media have long argued that the United States and NATO are responsible for the escalation of tensions in Ukraine. In Russian messaging, NATO is routinely depicted as a duplicitous and aggressive organization that broke a verbal agreement with Russia to not expand “one inch eastward” in the 1990s.

That China would also blame the United States and NATO for the war is hardly surprising. But Chinese amplification of specific Russian talking points—namely that the eastward expansion of the alliance both threatens Russia’s “legitimate security concerns” and violates earlier assurances—have increased dramatically in the past two months. Since February 1, 2022, monitored Chinese Twitter accounts have used the term “legitimate security concerns” more than 150 times to defend Russia’s actions in Ukraine. In the past two months, mentions of NATO’s eastward expansion have increased 500 percent in Chinese Twitter posts compared to mentions of the issue in Chinese posts in the entirety of 2021. These attacks have often included claims of an alleged broken promise made to Moscow or language suggesting Ukrainians were “deceived” by NATO.

Examples of Chinese diplomatic and state media accounts casting blame on the United States and NATO for escalating tensions between Russia and Ukraine.

Both Russia and China have also pointed to statements made by Western validators—from the usual suspects of state-backed propaganda to renowned journalists and academics—to support their position on NATO’s culpability.

The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Russian Embassy in Saudi Arabia citing similar arguments made by Western journalists and academics about NATO’s role in the crisis.

Although NATO and the United States are depicted as warmongers, China also has a vested interest in portraying NATO and the United States as feckless and unreliable partners, given Chinese concerns about possible U.S. support for Taiwan.

A CGTN reporter posts two cartoons accusing NATO of abandoning Ukraine in its time of need.

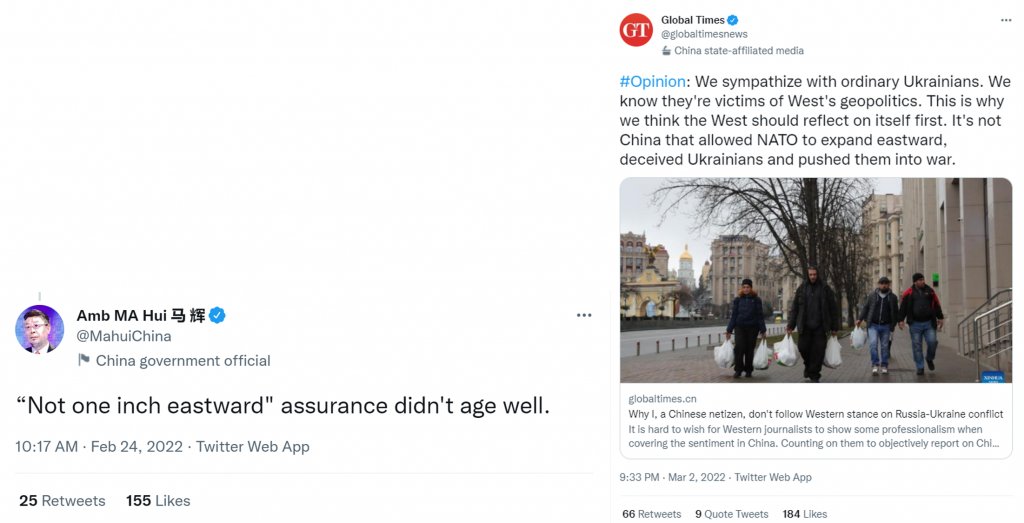

The prominence of Taiwan in China’s Ukraine messaging is evidenced by the fact that Taiwan is among the ten most mentioned countries or special territories in Chinese tweets referencing “Ukraine” between March 1 and March 12, 2020, despite having no role in the conflict.

The most mentioned countries in Chinese tweets mentioning Ukraine between March 1 and March 12, 2022.

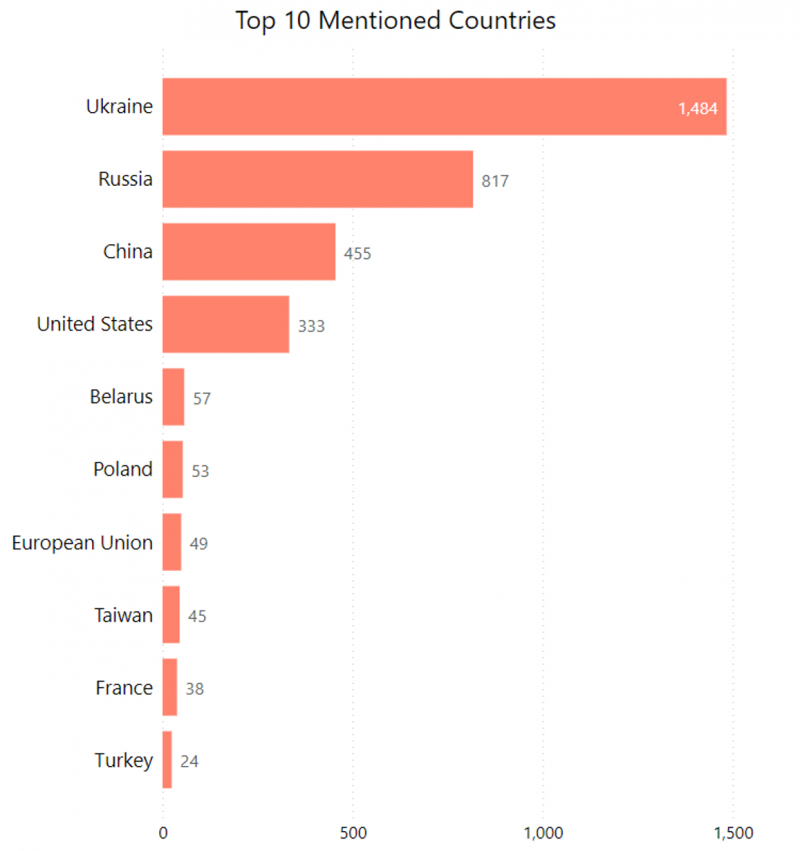

Depicting Ukrainians as Neo-Nazis

Since 2014, Russia has actively promoted the idea that Ukraine is a fascist and neo-Nazi state. This narrative, however, was almost completely absent from Chinese messaging prior to February 2022, when Putin made “denazification” the primary justification for war. Since that time, monitored Chinese accounts have tweeted more than 100 times about Nazis in Ukraine, at times directly amplifying Russian government officials and those affiliated with Russian state media outlets.

CGTN Europe amplifying Putin’s claim that the Ukrainian government is “a gang of drug addicts and neo-Nazis” and a Chinese diplomat in Lebanon retweeting former RT America host Lee Camp’s claims about U.S.-British support of “Nazi-linked” Ukrainian National Guard troops.

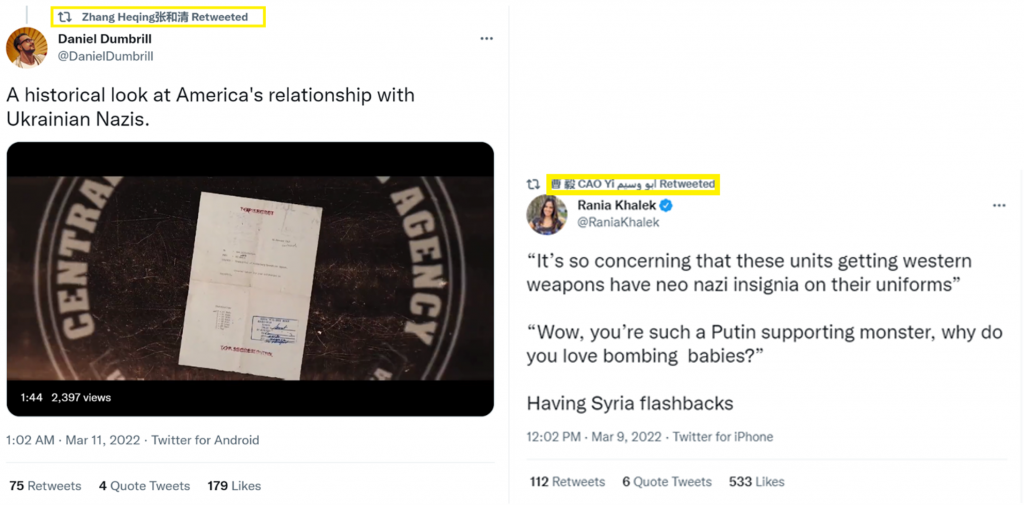

Given the sensitivity of the topic, Chinese diplomats have avoided using the term “Nazi” to describe Ukrainians; they have, however, amplified claims made by others about neo-Nazis in Ukraine. This is typically done through retweets of “anti-imperialist” influencers who frequently appear in both Chinese and Russian propaganda.

Retweets of Ukrainian neo-Nazi narratives by Zhagn Heqing, the Cultural Counsellor at the Chinese embassy in Pakistan, and Cao Yi, a diplomat in the Chinese embassy in Lebanon.

Falsely Suggesting that the United States is Producing Bioweapons in Ukraine

Perhaps the most concerning messaging relates to false claims that the United States is developing biological weapons laboratories in Ukraine. Throughout the coronavirus pandemic, China has spread similar false claims about U.S. bioresearch labs being responsible for the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus. These two disinformation campaigns are therefore mutually reinforcing and mutually beneficial, as evidenced by the fact that much of China’s public support for Russia’s Ukrainian bioweapons narrative includes references to the U.S. bioresearch lab in Fort Detrick, Maryland, the main target of China’s coronavirus disinformation campaign.

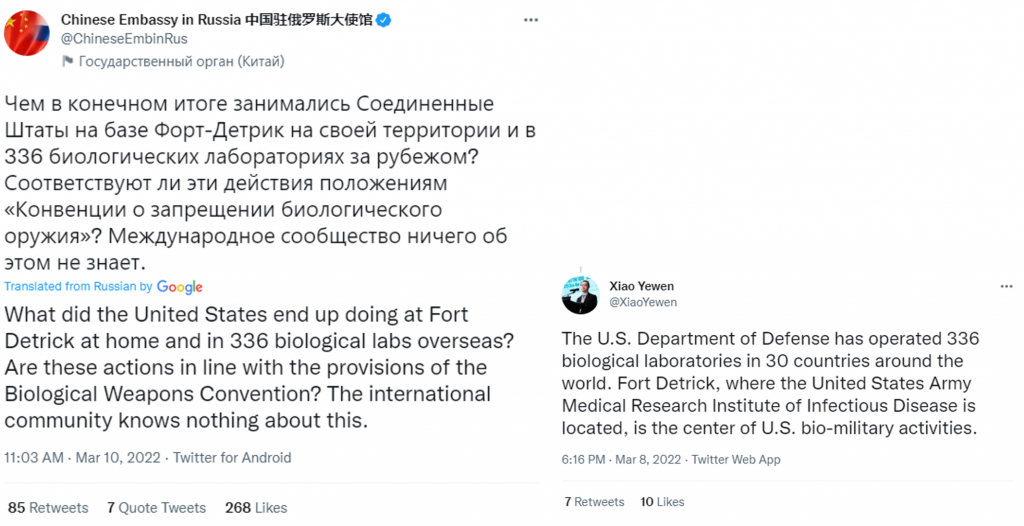

On March 6, 2022, the Russian Ministry of Defense claimed to have evidence that the United States is running 30 bioweapons labs in Ukraine. This follows a decades-long pattern of Kremlin-backed disinformation targeting U.S.-funded research labs, particularly those based in post-Soviet countries. Beijing’s amplification of Russia’s bioweapons disinformation has been substantial, and, by some metrics, has outpaced efforts by the Kremlin to promote its own claim. Between March 6 and March 12, 2022, for example, the term “lab” has appeared in more than 400 tweets from Chinese government officials and those affiliated with Chinese state media compared to 350 mentions in tweets from Russian government officials and state media personnel (both totals are likely to include some false positives). China’s intensive amplification effort has been driven by both diplomats and state media figures, who have used the opportunity to relaunch their efforts to cast blame on the outbreak of the coronavirus on the U.S.-based Fort Detrick lab.

Examples of Chinese diplomatic accounts re-upping efforts to cast suspicion on U.S. bioresearch labs, including Fort Detrick—the central target of China’s coronavirus disinformation campaign.

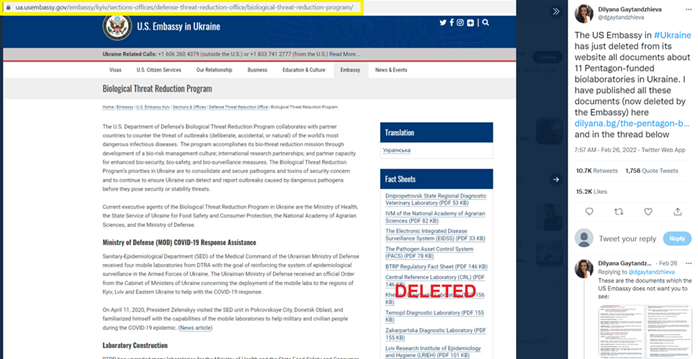

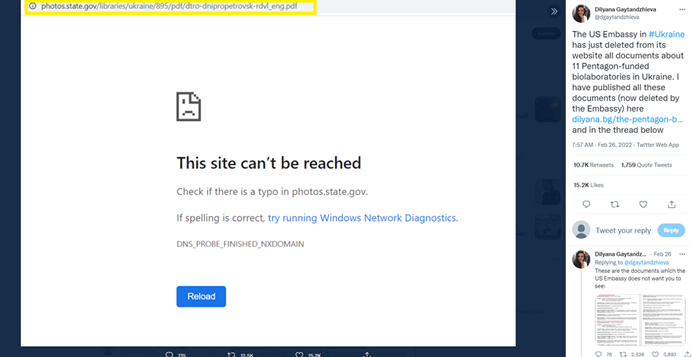

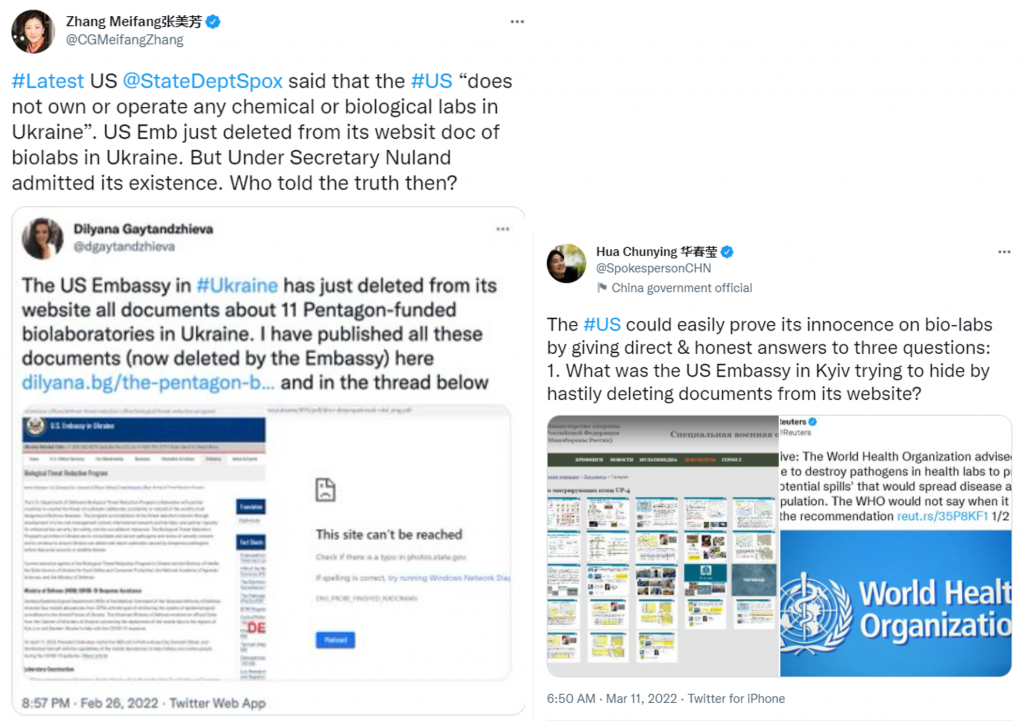

Beijing’s backing of Moscow’s latest bioweapons conspiracy has included direct amplification of disinformation pushed by a pro-Kremlin Bulgarian journalist, Dilyana Gaytandzhieva, who suggested that the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv “deleted” evidence of the existence of bioresearch labs from its website after the Russian allegations were made public. Gaytandhzieva, a frequent contributor to RT and Sputnik who has previously pushed similar and thoroughly debunked claims about bioweapons programs at the U.S.-funded Lugar Lab in Georgia, provided “evidence” of the embassy’s removal of documents in a tweet that has since received more than 12,000 retweets and 15,000 likes. That tweet, however, points to a defunct and entirely unrelated domain (http://photos.state.gov/) instead of the U.S. Embassy website (https://ua.usembassy.gov/), where the allegedly deleted documents remain available to the public.

Tweet from Dilyana Gaytandhzieva alleging to show the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine deleting evidence of its biological threat reduction program. Notice the URL below does not link to the embassy domain. All documents are still accessible on the embassy’s website.

Despite the rather obvious and crude manipulation effort, Gaytandhzieva’s tweet has been retweeted or cited by at least 14 Chinese government and state media accounts on Twitter, including Hua Chunying, the chief spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Retweet and references to Gaytandzhieva’s claim that sensitive documents were deleted from the U.S. Embassy website made by the consul general of China in Belfast and the spokesperson at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

China has marshalled the resources of its vast propaganda apparatus to lend credibility—both directly and indirectly—to Russia’s false claims of a U.S.-backed Ukrainian bioweapons program. Beyond the threat that Beijing’s support of Russian disinformation could create cover for a Russian chemical attack in Ukraine, its efforts also threaten global public health during the current and future pandemics.

Additional examples of Chinese state media and diplomatic and government officials promoting an Kremlin-created conspiracy theory about a U.S. bioweapons program in Ukraine.

This analysis suggests that Chinese diplomats and state media are not only amplifying pro-Russian messaging, but also stepping up false accusations against the United States, Europe, and Ukraine. For observers who hoped that Beijing could cooperate with Washington, Brussels, and others in pursuit of shared interests, this episode is deeply concerning. China’s stance on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine appears likely to do damage to the reputations of both countries abroad, further damaging already low levels of favorability in many advanced democracies.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.