TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew appeared on Capitol Hill on Thursday 23 March to testify in front of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, where lawmakers peppered him with questions about TikTok’s Chinese ownership, effects on youth, and practices around data collection. Chew assured the committee that TikTok functions independently of the Chinese Communist Party, but before and after the hearing, the Chinese government devoted significant state resources to defend the company—seemingly calling into question TikTok’s independence.

During the week of the hearing, we tracked Chinese state media and diplomatic activity on the Alliance for Securing Democracy at GMF’s Hamilton 2.0 dashboard. We found that Chinese diplomats and state media have mounted a sizable influence campaign in defense of TikTok, during which they have recycled familiar tropes and anti-US narratives in an effort to shape public opinion beyond China’s borders. These narrative efforts have generally followed five key trends.

Chinese diplomatic and state media accounts:

- Amplified the TikTok CEO’s statements to paint the app in a benign light;

- Hyped TikTok’s popularity and elevated the consequences of a ban;

- Criticized and mocked members of Congress;

- Denigrated the entire US political system and painted the United States as hostile to business; and

- Portrayed criticism of TikTok or China as xenophobic.

The fact that China feels compelled to defend TikTok so vociferously is notable. Chinese state media is primarily a vehicle the authoritarian one-party government uses to broadcast its worldview and shape perceptions, both internally and globally. The global dimension of state media outlets’ work has grown in importance since Chinese leader Xi Jinping came to power and insisted on spreading China’s “discourse power” by having state media “tell China’s story well”. A key component of this strategy to increase the reach and persuasiveness of the Chinese state’s worldview has been the denigration of its democratic rivals, first and foremost the United States. CGTN, Xinhua, and others incessantly portray the United States as dysfunctional, overbearing, and destructive.

Central to debates over TikTok’s role in democratic discourse is the risk that a Chinese government with an active propaganda campaign in support of TikTok and against US interests may be in a position to control future debates on the issue. As these debates continue over the coming weeks and months, a solid understanding of the Chinese government’s propaganda efforts on this issue is critical to evaluating the arguments within the United States. We do not know the details of how TikTok’s own algorithm sorts, promotes, or recommends discourse about the TikTok platform itself. But Chinese state media is making a significant effort to shape perceptions of the app on other social media platforms, demonstrating the positions and narratives China is attempting to sow in the United States and globally.

By the Numbers

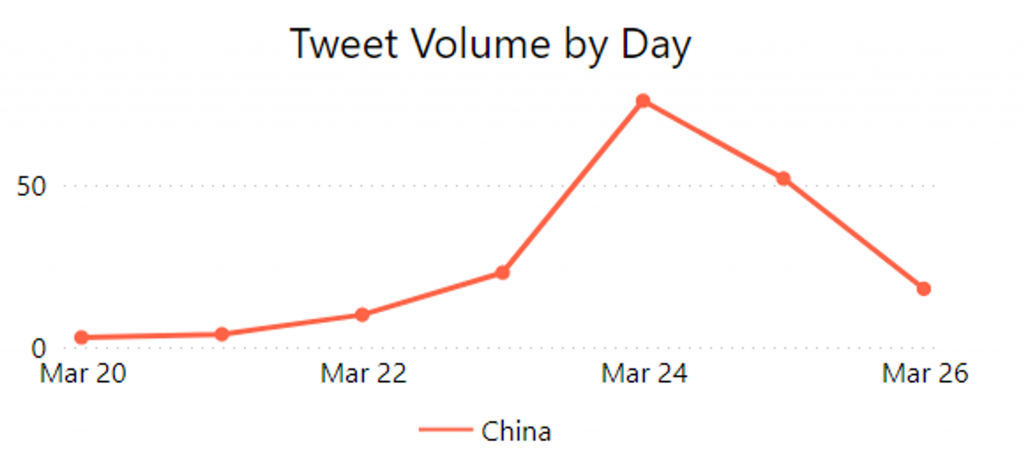

Between March 20 and March 26, 2023, Chinese diplomats and state media tweeted about TikTok nearly 200 times. By way of comparison, those same accounts mentioned the company fewer than 150 times over the entirety of January and February 2023. There was a noticeable spike in activity in the immediate aftermath of the hearing, with Chinese accounts mentioning the social media platform more than 75 times on March 24 alone. The focus was clearly on US action related to Thursday’s hearing.

China is usually the most often mentioned country in tweets put out by Chinese diplomatic and state media accounts; however, Chinese tweets about TikTok mentioned the United States 50% more often than China last week.

Number of tweets from Chinese accounts mentioning “TikTok” between March 20 and March 26, 2023.

A significant portion of the propaganda push came from Chinese state media accounts, which accounted for more than half of these tweets and also ran more than 30 stories about TikTok in outlets such as People’s Daily, China Daily, and Global Times.

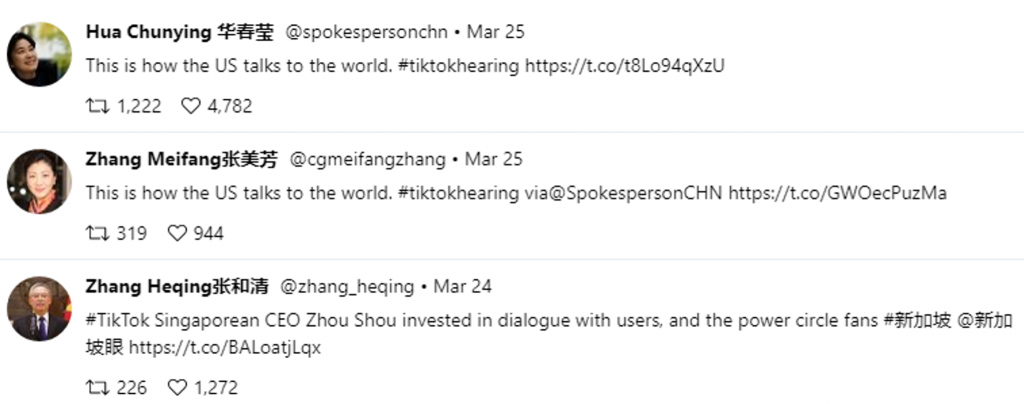

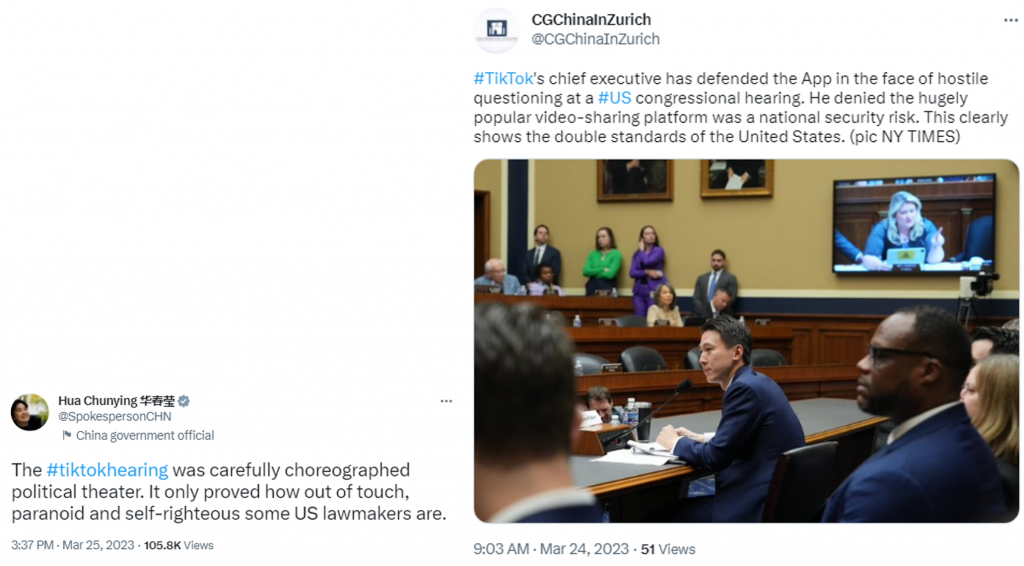

Chinese diplomats also came to the platform’s defense in a significant way, with 80 diplomatic tweets mentioning the social media company last week. Their impact was noteworthy; looking at all monitored Chinese accounts’ tweets mentioning TikTok last week, diplomatic accounts were behind the three tweets that generated the most engagement.

Top 3 most retweeted tweets from Chinese accounts mentioning “TikTok” between March 20 and March 26, 2023.

Many Lines of Defense

Chinese diplomatic and propaganda efforts around TikTok trotted out familiar themes: They appealed to xenophobia; denigrated the US system of government; and painted the United States as paranoid, undemocratic, and hostile to business because of the TikTok conversation. They also sought to hype up the app’s success, highlight China’s strong opposition to a forced sale, and amplify TikTok users’ opposition to a ban.

The Official Position

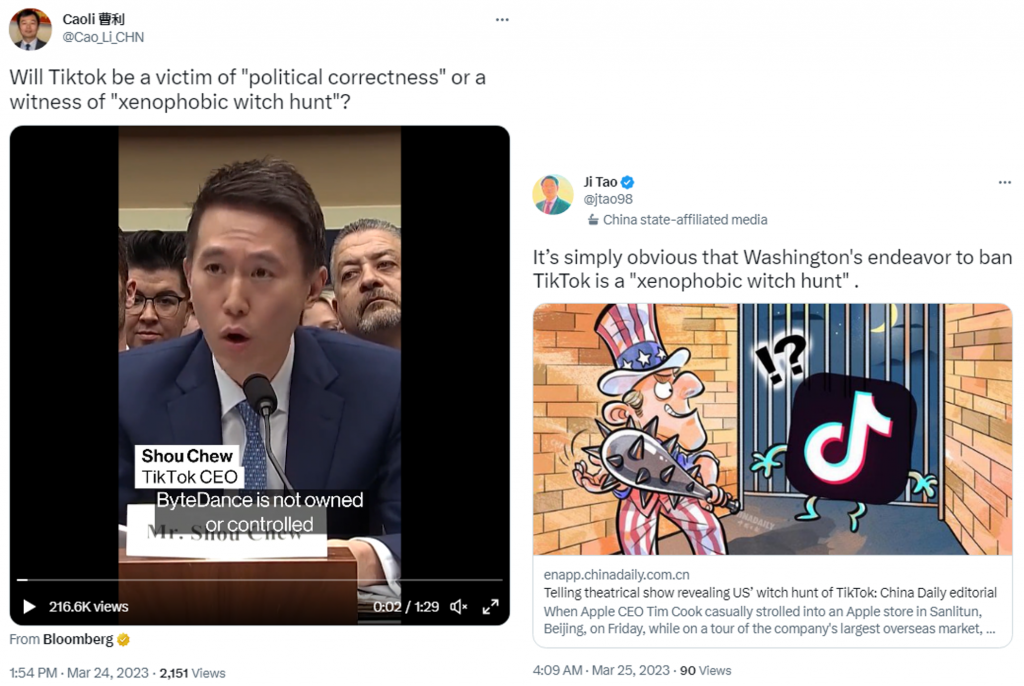

On Friday, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) spokesperson Mao Ning delivered China’s official position in response to Thursday’s hearing. She argued that there was no evidence that TikTok was a threat to US national security and quoted a US lawmaker who called the move toward a ban a “xenophobic witch hunt”. This position is consistent with earlier MFA pronouncements that accused the United States of “overstretch[ing] the national security concept (…) to hobble foreign companies”. Despite the brevity of the MFA’s comments, some Chinese diplomats and many state media outlets relayed them.

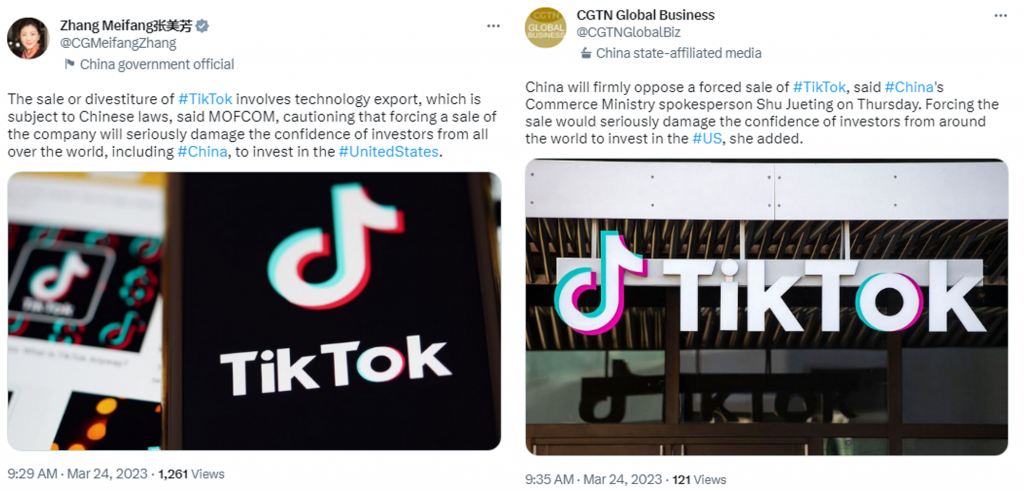

Another point that previously prompted an official reaction from the Chinese government is the US proposal to organize a sale of TikTok to a company other than its current Beijing-based owner, Bytedance. The Chinese Ministry of Commerce voiced clear opposition to the idea, arguing that such a sale would damage investors’ confidence in the United States. Several diplomats and state media, including CGTN Global Business, amplified this argument.

Amplifying the TikTok CEO’s Statements to Paint the App in a Benign Light

While the most recent MFA reaction may prompt Chinese diplomats to deploy more efforts to defend TikTok, so far it has been state media that has most actively defended the social media platform. In the run-up to the hearing, Chinese outlets highlighted TikTok’s CEO’s statements assuring Congress that safety was a “top priority” and bemoaning “misconceptions” about his company.

Hyping Up TikTok’s Popularity and the Consequences of a Ban

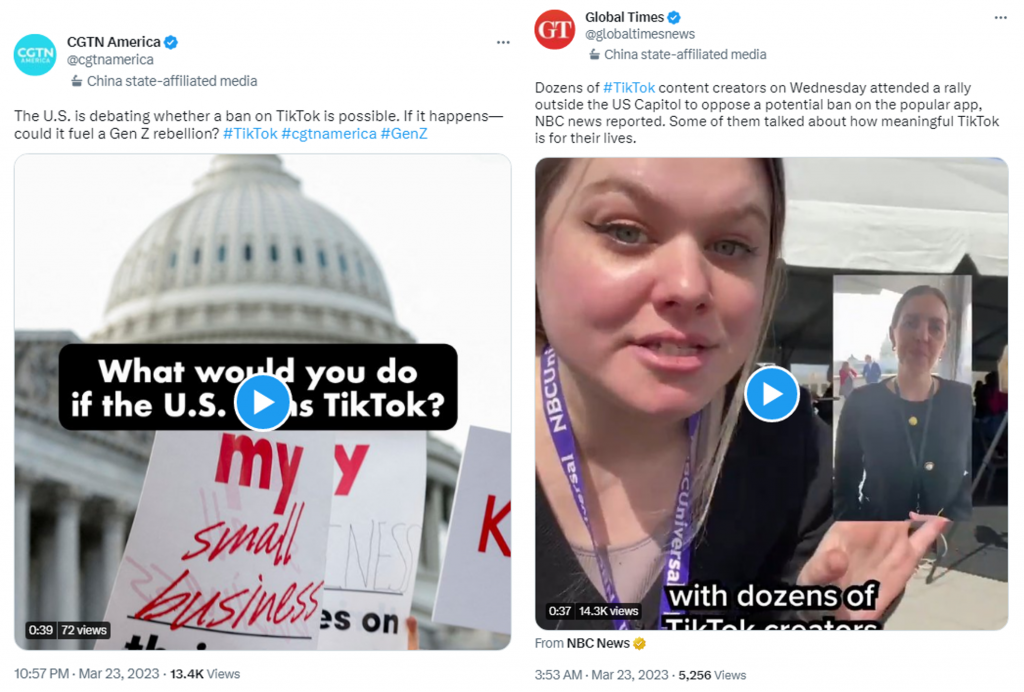

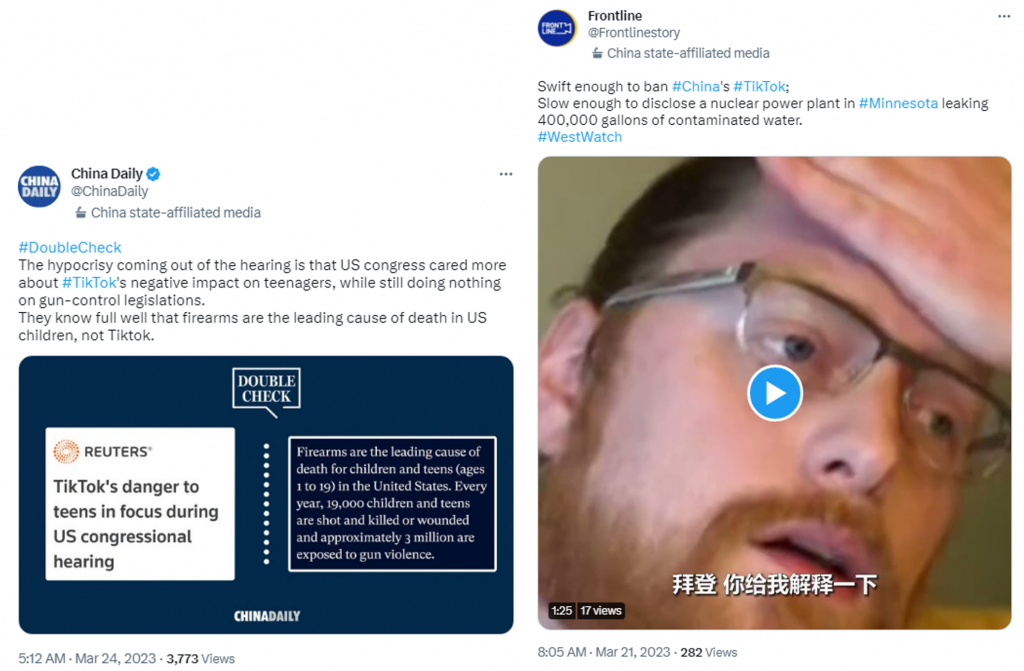

Chinese state media also consistently highlighted the platform’s success and popularity with US citizens, especially among younger demographics. At times, this hyping up of TikTok also turned more threatening with CGTN America wondering whether a ban would “fuel a Gen Z rebellion” and other outlets forcefully highlighting how attached users and content creators are to the platform.

Criticizing and Mocking Members of Congress

Chinese diplomats also criticized the hearing directly. Assistant Foreign Minister Hua Chunying found the representatives “out of touch [and] paranoid”, while the Chinese consulate in Zurich argued the hearing exhibited “the double standards of the United States”. On the state media side, several outlets questioned the competence of US lawmakers, calling them “old” and “internet-illiterate”. Similar narratives mocking members of Congress also seemed to spread among TikTok users in the United States.

Denigrating the US System and Painting the United States as Hostile to Business

Other Chinese accounts went even further and used the proceedings against TikTok to denigrate the entire US system. China Daily called out US lawmakers’ “hypocrisy” over their inaction on gun violence despite their claims that they wanted to help teenagers. And CGTN affiliate Frontline amplified a video angrily comparing inaction over a nuclear leak in Minnesota with Congress’ attention to TikTok. Diplomats and state media also used Apple CEO Tim Cook’s recent visit to China to compare Beijing’s supposed openness to trade with Washington’s hostility to tech companies. (The irony here is of course that many US companies—including major social media platforms—are completely banned in China.)

Portraying Criticism of TikTok or the Chinese Government as Xenophobic

Finally, China’s messengers accused the United States of xenophobia and of wanting to ban everything Chinese. In the aftermath of the MFA’s comments calling the hearing a “xenophobic witch hunt”, several diplomats and state media reporters relayed the argument that the United States was acting primarily out of prejudice. Whereas the ultranationalist tabloid Global Times had previously been the main voice promoting this narrative, the MFA seems to have signaled that this is now a legitimate line of argument to use when defending the social media platform.

Looking Ahead

When it comes to hot-button topics involving autocratic actors, it can be difficult to tell the difference between organic arguments and arguments derived from autocratic propaganda, even in open, democratic information spaces. Should geopolitical debates occur on Chinese-owned social media platforms like TikTok going forward, it could become even more difficult to differentiate between organic arguments and propaganda.

Among the chief national security concerns with TikTok identified by researchers and policymakers is the ability of a Chinese-owned social media app to conduct targeted influence operations in the United States and other democracies. The access to user data and preferences collected by social media apps, as well as opaque algorithmic content selection, creates fertile ground for influence operations. And despite professions of distance between TikTok and China, the Chinese government has a demonstrated interest in influencing global discourse about the app. If the Chinese government were to influence TikTok into artificially boosting Chinese state media narratives—for example, employees could use TikTok’s “heating” button to manually make specific content go viral, as they have reportedly done before—it would be extremely difficult to tell.

Today, the Chinese propaganda we study floods Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube with anti-US content designed to boost China’s image. Tomorrow, the same debates over issues critical to the information and geopolitical contests between China and democracies may take place on TikTok itself, potentially making it more difficult to distinguish fact from propaganda.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.