As COVID-19 has spread around the world, the Chinese party-state’s international propaganda apparatus has swung into action. The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) propaganda outlets are using declining numbers of COVID-19 sufferers inside China to portray its response as an example to countries struggling with growing caseloads and to hold itself out as a provider of global public goods at a time when the United States has ceded leadership. In doing so, the Party is adeptly repackaging old, internally directed propaganda themes for an external audience, demonstrating its ability to tailor the message based on the target audience. At the same time, it is also experimenting with new forms of disinformation that resemble those Russia uses.

China as an island of CCP-provided stability in a chaotic world is an old trope of Party propaganda. The CCP is increasingly adapting this theme to international audiences — a goal CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping laid out when he exhorted state media to “use methods that overseas readers enjoy and accept, and language that they can understand, to explain the China story, [and] transmit China’s voice.”

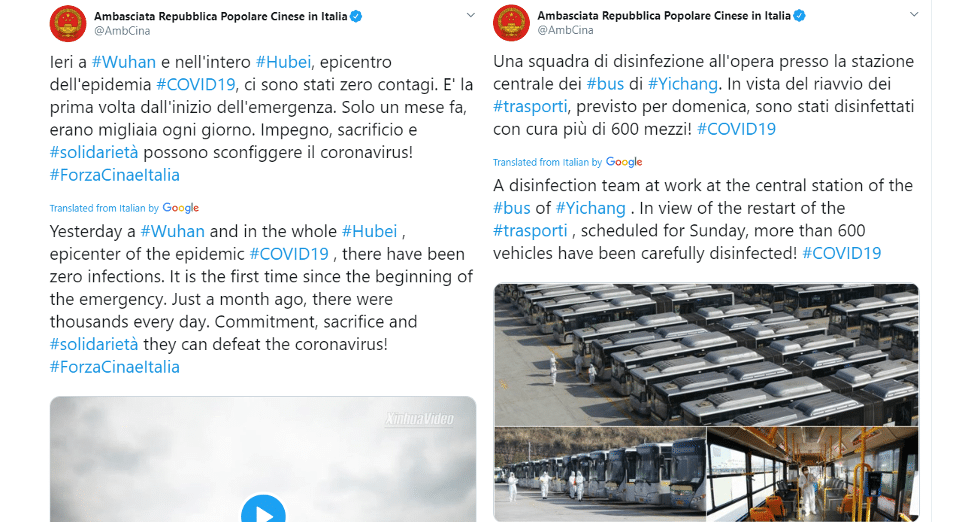

CCP propaganda directed at Italy is a useful example of this. Many of the popular tweets from the Beijing’s embassy in Italy have sought to hold out China’s response as a model, implicitly demonstrating the efficiency and effectiveness of its authoritarian system.

Other popular tweets have focused on China’s willingness and ability to provide material and technical support to Italy’s strained medical infrastructure.

Solidarity is another important theme: one of the embassy’s most popular tweets is a pair of drawings. The first thanks Italy for its support of China during the devastating Wenzhou earthquake of 2008. The second shows China supporting Italy in its time of need. The text of the tweet reads, “You may have forgotten, but we will remember forever. Now it’s up to us to help you.”

The embassy did not commission the drawings; rather it identified and elevated memes already circulating within the Party-curated internet inside China, repurposing them for external audiences in a sophisticated blending of propaganda and public diplomacy.

During the COVID-19 crisis, the CCP has also demonstrated its ability to tailor its message to the concerns of its audience. Top tweets from Beijing’s mission to the EU have targeted European anxieties over a perceived American withdrawal from important global institutions by emphasizing China’s willingness to cooperate internationally, as well as its contributions to international public health organizations, particularly the World Health Organization (WHO). Many of the mission’s tweets on International Women’s Day highlighted the contributions of female emergency responders in China, seeking to position China as a champion of feminist ideals to a Brussels audience, despite most observers agreeing that progress on women’s issues in China has gone in retrograde since Xi Jinping took power.

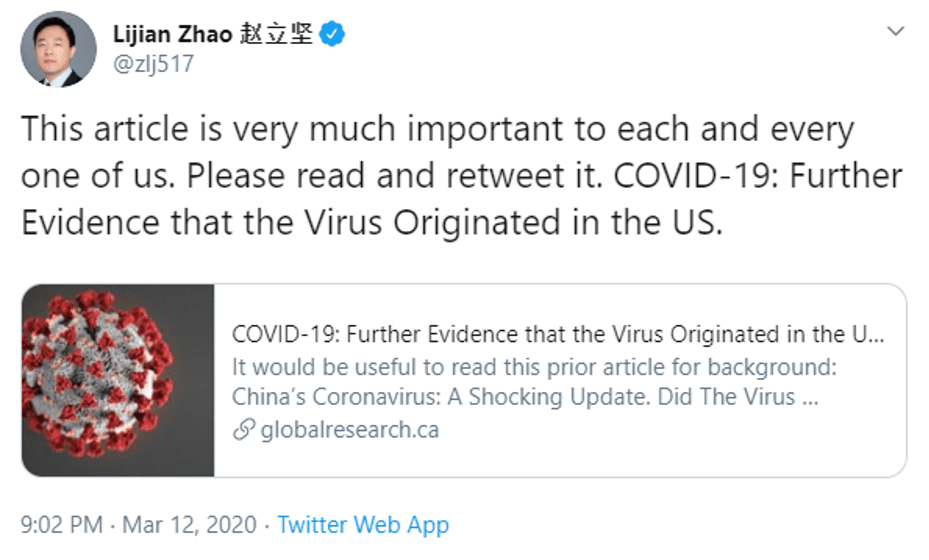

Meanwhile Chinese government officials have promoted baseless conspiracy theories about the virus’s origins, claiming that the United States military brought it to Wuhan. Zhao Lijian, a spokesperson for the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, retweeted one such article from the fringe conspiracy website Global Research.

Zhao’s tweet was retweeted by Chinese ambassadors to 12 countries, most in Africa, in what could be seen as a play to build on Russia’s efforts to spread conspiracy theories on the African continent that AIDS was a biological weapon developed by the United States. Spreading conspiracy theories through official channels — a long-standing Russian tactic — may signal a new phase in Beijing’s external propaganda efforts. Doing so may seem to conflict with an image of China as a calm, reassuring global presence. But the state’s propagandists may simply be embracing the internet’s ability to communicate many different messages to many different audiences simultaneously. As COVID-19 continues to spread, the CCP will continue to follow Xi Jinping’s instructions to “tell the China story well”; what that story is appears to depend increasingly on what the Party believes the listener wants to hear.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.