When Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian began tweeting about the origins of the coronavirus in March, it marked a significant turning point in China’s social media disinformation operations. While China has long deployed widespread censorship, propaganda, and information manipulation efforts within its borders, information operations directed at foreign audiences have generally focused on framing China in a positive way and casting doubt on events and narratives that reflect poorly on the party-state. In the past, this has included using state media as well as covert social media campaigns to promote, for example, stories alleging that the 2019 Hong Kong protests may have been connected to the CIA and that Uighur detention camps do not exist.

In the last two months, however, Beijing has conducted a much more ambitious effort not only to shape global perspectives about what’s occurring inside China, but to influence public opinion about events outside its borders.

This new approach is exemplified by the dramatic uptick in the number of Chinese diplomats leveraging western social media platforms. On Twitter, there has been a more than 300 percent increase in accounts associated with Chinese embassies, ambassadors, and key government officials since April 2019. Borrowing a page from the Russian playbook, these accounts, with the assistance of state-controlled media outlets, have promoted multiple and at times conflicting conspiracy theories asserting U.S. responsibility for the pandemic. Iran and Russia have joined in with a concerted effort to push Chinese social media conspiracies to new heights. The United States now finds itself in a multi-front social media war against a triad of disinformation stretching from Moscow to Tehran and Beijing.

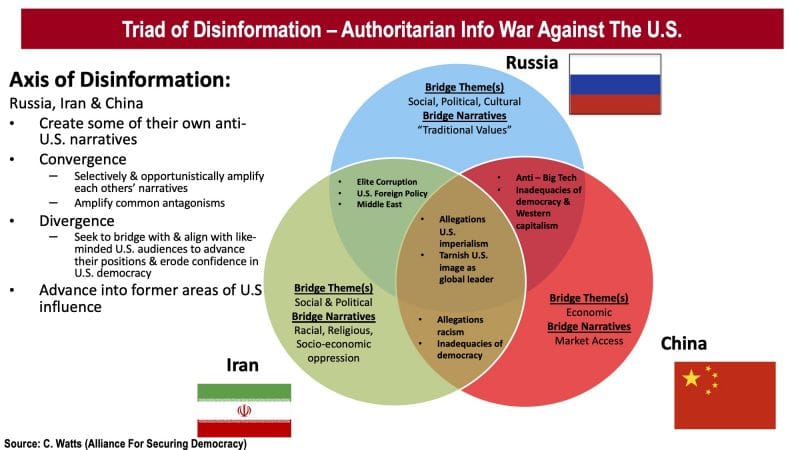

The mutually reinforcing streams of anti-U.S. information operations do not appear to represent an overt, established alliance between these authoritarian regimes, but rather the present convergence of the aims of three American adversaries. Russia, Iran, and China have divergent foreign policy goals in many respects, but a common adversary in the United States. By opportunistically reinforcing each other’s information manipulation efforts, the cumulative sum of their efforts is greater than its individual parts. It also allows each country to concentrate on its comparative advantages. Russia’s tremendous capacity for content production and programming in multiple languages offers China and Iran cost savings and extended reach. China’s Twitter attacks on America provide the Kremlin an information warfare proxy. Iran’s haughty, aggressive anti-American claims allow Russia and China to advance narratives they’d rather not put forth under their own names.

Since January 1, 2019, a team at the Foreign Policy Research Institute has analyzed more than 8,700 Russia Today, Sputnik News (Russia), PressTV (Iran) and Global Times (China) stories. Several patterns are apparent in this dataset. All three countries promote narratives that cast the United States as an aggressive, imperialist country seeking to dominate the world. The emphasis shifts, however, when the scope is limited to narratives conspicuously promoted by only two of the three regimes. Bilateral convergence between Russia and China arises in their denigration of American technology companies and of the relationship between Washington and Silicon Valley, as well as vocal support for Chinese tech companies like Huawei. Russian and Iranian efforts converge in opposition to U.S. foreign policy, especially in the Middle East, but also in other areas of overlapping interest like Latin America. Chinese and Iranian narratives focus on highlighting racial injustice in America, and casting it as a fundamentally racist country with no standing to promote democracy or human rights.

Narrative convergence online naturally fails to reflect the deep-seated differences between these three countries with respect to their foreign policy goals and the ideologies of their ruling regimes. In fact, an analysis of the substance of this content reveals that each of these authoritarian regimes aims to influence a different segment of the American electorate. Russia, Iran, and China all seek to build bridges to receptive American audiences that are sympathetic to elements of their worldview, and who may be willing to advocate for changes in U.S. policy favorable to their strategic objectives. As witnessed in the electoral interference in 2016, Russia overtly and covertly sought out and continues to establish people-to-people and party-to-party alliances with white nationalists, Christians, and other supporters of “traditional values.” Iran, by contrast, being neither predominantly Christian nor predominantly white, seeks out common cause with American minority groups oppressed or disenfranchised based on race, religion, or economic status. While Russia’s struggle with the United States is chiefly political, China’s is primarily economic, and leverages its enormous market of consumers to cultivate influence within U.S. multinational corporations. China’s standoff with the NBA in 2019 should be seen as a canary-in-the-coal-mine for coming clashes between democracy and authoritarianism in the social media space.

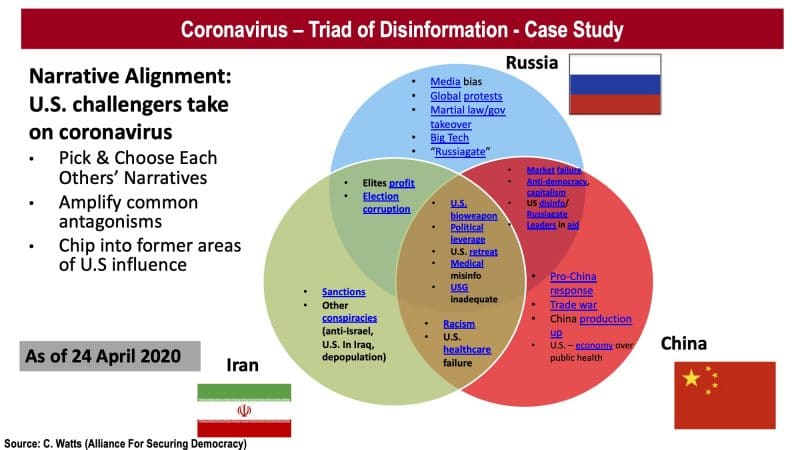

The coronavirus pandemic has brought authoritarian narrative convergence against the United States to new heights. China, the source of the global pandemic, has continued to tout its global outreach, emphasizing aid efforts to other countries afflicted by the virus and citing the trade war as a barrier to fighting the pandemic. Russia has continued its standard active measures approach, inciting fears of martial law, class warfare, and government takeovers, while simultaneously alleging that coronavirus hysteria represents yet another attempted media takedown of President Trump. Iran has offered up the consistent claim that U.S. sanctions are to blame for their inadequate response to coronavirus, while also suggesting that an Israeli-U.S. partnership might have created the virus.

As pairs, the countries have come together in unsurprising ways to challenge the United States with manipulated information about coronavirus. China and Russia reinforce each other’s claims that American democracy is central to the coronavirus challenge, and that U.S. policymakers are to blame. Russia and Iran have used coronavirus precautions and resulting delays in the voting process as evidence of electoral corruption, while also amplifying narratives of elite profiteering at the hands of the poor. China and Iran use coronavirus to level charges of racism, while highlighting inadequacies in the U.S. healthcare system.

Zhao Lijian’s tweets rewriting the history of the emergence of coronavirus represent the thrust of coronavirus convergence between the three countries. Iran, Russia, and China have collectively sought to cast doubt about the Chinese origin of the coronavirus, and suggest it is a U.S. biological weapon released into Wuhan. At a time when the U.S. is taking a less active role in many international institutions, and relations with many key allies are fraught, China and Russia are engaged in a full-spectrum effort to shape the information environment. They have deployed a narrative that serves to undermine American creditability, while simultaneously reaching out to American allies like Italy with coronavirus aid and messages of goodwill and solidarity. Alongside the specific bogus claim of coronavirus being an American bioweapon, these countries have also advanced swaths of medical misinformation that further confuses world audiences about the origin, advance, containment, and treatment of coronavirus.

Zhao Lijian’s tweets rewriting the history of the emergence of coronavirus represent the thrust of coronavirus convergence between the three countries. Iran, Russia, and China have collectively sought to cast doubt about the Chinese origin of the coronavirus, and suggest it is a U.S. biological weapon released into Wuhan. At a time when the U.S. is taking a less active role in many international institutions, and relations with many key allies are fraught, China and Russia are engaged in a full-spectrum effort to shape the information environment. They have deployed a narrative that serves to undermine American creditability, while simultaneously reaching out to American allies like Italy with coronavirus aid and messages of goodwill and solidarity. Alongside the specific bogus claim of coronavirus being an American bioweapon, these countries have also advanced swaths of medical misinformation that further confuses world audiences about the origin, advance, containment, and treatment of coronavirus.

What can the U.S. and the West do to counter authoritarian disinformation?

The United States presently faces a sustained effort, largely unfolding on social media platforms and websites hosted in the Western world, to undermine American legitimacy and subvert its democracy. This concerted effort may in the coming months convince many around the world of the falsehood that the United States created the coronavirus as a bioweapon. This collective effort has taken advantage of America’s retrenchment in global affairs, inconsistent foreign policy, and lack of a coherent and centralized message about coronavirus in the short-term and America’s role in the world over the long-term. These disinformation peddlers stand poised to write an alternative history, in large part because authoritarians have been consistent, sustained, and disciplined in their messaging, while the United States has not.

The United States and allied democracies can counter authoritarian states by pursuing several efforts in tandem:

- Lead by example. The United States and other democracies must stand up for science-based approaches to global policy challenges by supporting and taking an active role in and financially supporting multilateral organizations like the World Health Organization (the opposite of what’s recently happened).

- Work with tech companies to downrank, demonetize, and de-platform authoritarian state-sponsored news outlets and social media accounts spreading manipulated information that threatens public safety and public health. Twitter has done this on several occasions in recent weeks, removing fringe news sites for coronavirus violations. While nefarious political influence and hate speech remain difficult to consistently police, threats to public safety, such as it relates to the coronavirus pandemic, are much easier to adjudicate. Broad systematic enforcement action on mainstream platforms could enforce a sizable reduction in authoritarian reach into Western audiences.

- Develop counter-messaging strategies designed to stress and undermine the credibility of authoritarian networks. For example, Russian propaganda appeals to white nationalists and orthodox Christian audiences to the exclusion of other minorities. Iranian propaganda focuses heavily on the persecution of racial and religious minorities. And both Iranian and Chinese officials use Western social media platforms that are banned domestically within their countries. The United States could seek to expose these contradictions amongst these authoritarian allies by strategically messaging in selected audience spaces. A nimble messaging campaign might be aimed at international discussions about the conflict in Syria, in which Iran and Russia are complicit with the Syrian government in the massacre of Muslim civilians perceived as disloyal.

Presently, the voices promoting discredited anti-American conspiracy theories are growing louder in the social media space. The United States and other democracies must move to rapidly rebut and repeatedly counter such narratives with facts and evidence. Further analysis of open source material must aim to evaluate the degree of cooperation on information manipulation taking place between and among authoritarian states. Unpacking this relationship, though, requires evaluating how states disseminate and amplify manipulated information, and will be the subject of my next post: “How To Build A Disinformation Bonfire.”

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.