Over the past three weeks, American and Chinese officials have employed escalating rhetoric in efforts to blame one another for the global coronavirus pandemic. High-ranking U.S. administration officials frequently and pointedly referred to the virus as the “China virus” or “Wuhan virus,” drawing sharp criticism from Chinese Communist Party officials and media outlets.

Fortunately, over the past several days, the administration appears to be shifting toward less inflammatory language. That’s a good thing for many reasons — not least because Asian-Americans in the United States have come under racist attacks. It’s also because the use of inflammatory terms has created an opportunity for Beijing to exploit. According to data captured by the Hamilton 2.0 dashboard, which tracks official Chinese messaging, Beijing’s criticism of the inflammatory language frequently overlapped with its promotion of conspiracy theories about the origins of the virus. That’s not to equate the administration’s rhetoric with disinformation, or to suggest that it is the only thing fueling Beijing’s propagation of conspiracy theories — it is almost certainly is not. But it is an important dynamic to track.

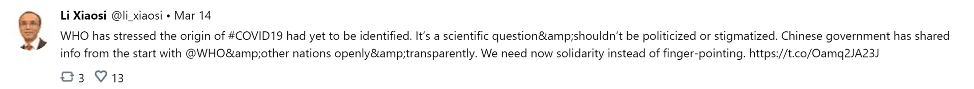

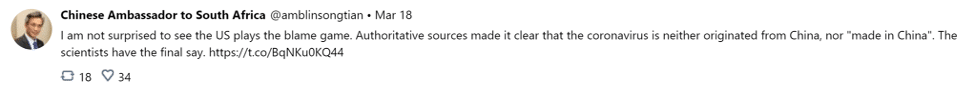

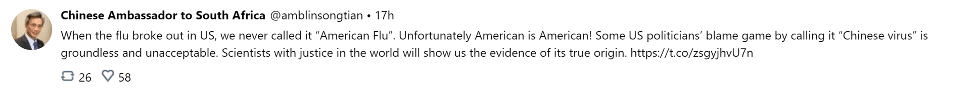

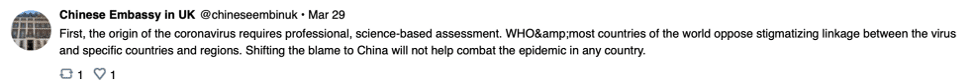

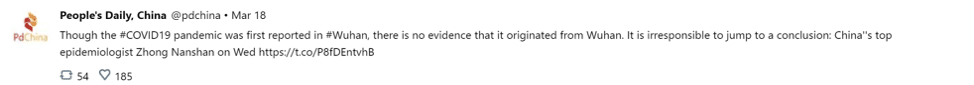

On Twitter, China’s ambassadors to Austria and South Africa each pushed back on what they characterized as “finger-pointing” and a “blame game” with suggestions that the coronavirus did not originate in China, or more broadly, that its origins are unknown. Similarly, China’s embassy in the UK, in criticizing U.S. leadership for “shifting the blame,” appeared to suggest that “professional, science-based assessment” of coronavirus’s origins have not been conclusive.

All of this comes at a time when China’s diplomatic corps has been dramatically increasing its presence on Twitter (which is blocked inside China). Over the past year, since the beginning of April 2019, the number of accounts run by Beijing’s diplomats has grown more than 250 percent.

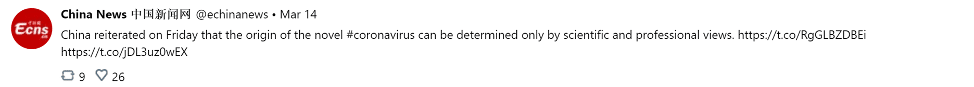

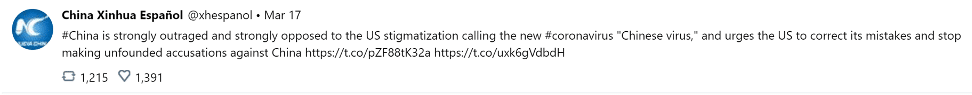

These claims by Beijing’s diplomats were then boosted by China’s state news media on Twitter, highlighting the interplay between government actors and the broader party-state media ecosystem. Some of these stories generated substantial engagement: a March 17 tweet from China Xinhua Espanol calling the “China virus” term an “unfounded accusation” was among the top ten most retweeted posts captured by Hamilton 2.0 that day, and the most retweeted China Xinhua Espanol tweet of that week.

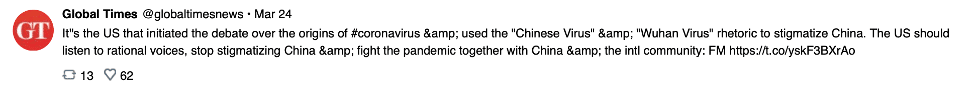

China’s state news websites did the same. One such piece, which ran in the Global Times, asserted that “US politicians have been contending the novel coronavirus is ‘Made in China,’ while global scientists, including those in the US, have not found strong evidence to prove the virus’ origin.” Another cited widespread praise for this behavior as a “smart move,” which entailed “us[ing] the American officials’ tactics against themselves.” Since these are English-language news stories, they are likely intended for an external audience.

“US sparks word war against China on COVID-19,” Global Times, March 13, 2020.

“Heated online discussions were sparked by the latest tweets by outspoken Chinese diplomat Zhao Lijian, who questioned the transparency of the US epidemic response mechanism, following the Trump administration’s all-out campaign to smear China on its handling of the coronavirus crisis, as part of an information war embedded with racial discrimination and malicious accusations. Zhao fighting back on social media was praised by the Chinese public as a “smart move” to use the American officials’ tactics against themselves.”

“FM says origin of virus must be based on science,” China Daily, March 14, 2020.

“China reiterated on Friday that the origin of the novel coronavirus can be determined only by scientific and professional views. The remarks were made by Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang at a daily news briefing as comments have been made saying the virus might have been brought to Wuhan by the United States military.”

“US urged to release health info of military athletes who came to Wuhan in October 2019,” Global Times, March 25, 2020.

“US politicians have been contending the novel coronavirus is “Made in China,” while global scientists, including those in the US, have not found strong evidence to prove the virus’ origin. Given this situation, it is important to trace any suspicious points, the US delegation to the Wuhan games in this scenario, and find out what really happened, Li said.”

“Scientists worldwide search for coronavirus origin,” Global Times, March 29, 2020

“A Beijing-based expert on epidemic prevention and control, who asked not to be named, said that regardless of the origin – China, the US or somewhere else – it was a question of science, not politics, which required cautious investigation based on science and facts. ‘If the politicians, especially some in the US government, would like to hype it for political purposes to pass the buck, that will surely interrupt scientists from doing their jobs,’ the expert said.”

That inflammatory or polarizing content produced by domestic actors, in this case the use of the term “Wuhan Virus,” provides fodder for information operations waged by foreign governments is not a surprise. Russia has long used this tactic, among others, to undermine a fundamental element of democracy by creating the impression that there is no such thing as objective truth. But promoting multiple, conflicting conspiracy theories is not a tactic typically used by China’s government, which has historically been more subtle in its information manipulation approach. That approach has typically focused on suppressing critical content and amplifying positive coverage — whether by coopting or establishing media outlets or using domestic social media platforms to dominate the digital space — rather than promoting outright disinformation on Western platforms.

Beijing’s information strategy appears to have changed in recent weeks — one of many facets of geopolitics the coronavirus has upended in its wake. How that strategy unfolds — including whether these changes stick or constitute a one-time departure — and how the United States engages will have implications for the contest between democrats and autocrats.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.