Clint Watts is Non-Resident Fellow at the Alliance for Securing Democracy and Distinguished Research Fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. He is the author of Messing With The Enemy: Surviving in a Social Media World of Hackers, Terrorists, Russians and Fake News.

This is part one of a three part series. This brief outlines the APM threat spectrum, but does not discuss what should be done to stop them. A follow-up brief on “Intelligence-led Social Media Defense” will offer a broader strategy for governments and social media companies to tackle this wide range of perpetrators.

Western democracies have pummeled social media companies for their failures to mitigate falsehoods and propaganda. Most states agree that terrorist activities on social media are a security threat that necessitates regulation and their legal regimes reflect this. Yet, just as the social media goliaths were making progress on this front, the rise of disinformation on their platforms emerged as a potentially existential threat to them and to democratic states more generally. It turns out that terrorists are easier to police online than authoritarian regimes, like Russia’s, that exploit cyberspace to quash their domestic opponents and undermine their adversaries abroad.

Social media companies cannot count on universal agreement among governments as to what disinformation is, and whether and how it should be policed. Meanwhile, they have struggled to maintain market access to regimes that exploit their platforms to suppress internal dissent and wreak havoc abroad. Thus disinformation, not violent discussion, is and will be for the foreseeable future the greatest, and possibly terminal, threat to social media companies.

A decade ago, there was a similar problem in tackling the toughest cyber threats. Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) actors emerged, conducting sophisticated, well-resourced hacking efforts that access networks and remain undetected inside them for prolonged periods. They employed a wide range of hacking techniques to dismantle their opponents. Sophisticated organized crime groups and countries seeking the asymmetric advantages cyberspace offers developed entire workforces dedicated to pursuing targets year after year.

Western companies and governments have undertaken approaches for understanding and combatting APTs that can be instructive for social media companies as they defend against the greatest challenge in their history. Tackling the most advanced threats to platforms requires a new, sustained approach to thwart nefarious manipulation. This intelligence-driven approach begins with an improved understanding of the threat actors and the methods they deploy via social media.

Advanced Persistent Manipulators

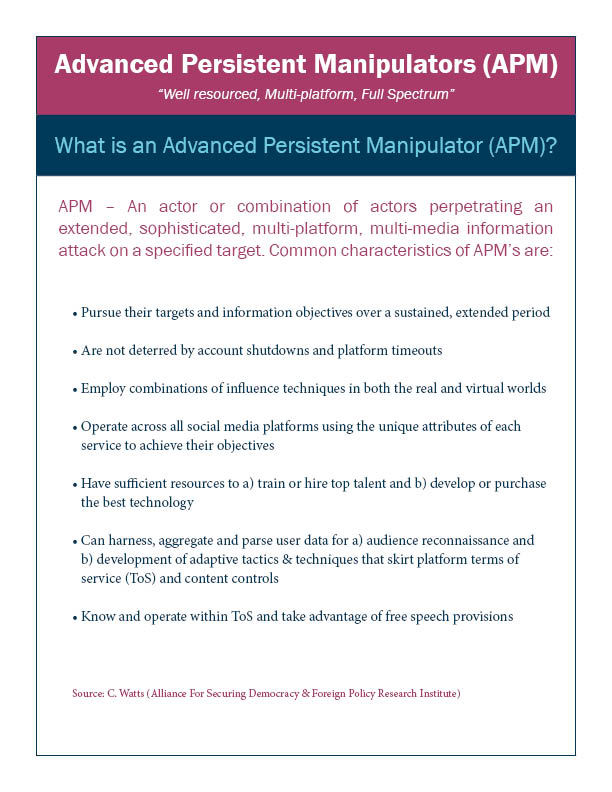

Similar to the challenge APT actors have posed to information and cyber security professionals, social media companies now face malign actors that can be labeled as Advanced Persistent Manipulators (APMs) on their platforms. (See Figure 1.) These APMs pursue their targets and seek their objectives persistently and will not be stopped by account shutdowns and platform timeouts. They use combinations of influence techniques and operate across the full spectrum of social media platforms, using the unique attributes of each to achieve their objectives. They have sufficient resources and talent to sustain their campaigns, and the most sophisticated and troublesome ones can create or acquire the most sophisticated technology. APMs can harness, aggregate, and nimbly parse user data and can recon new adaptive techniques to skirt account and content controls. Finally, they know and operate within terms of service, and they take advantage of free-speech provisions. Adaptive APM behavior will therefore continue to challenge the ability of social media platforms to thwart corrosive manipulation without harming their own business model.

Figure 1

Outlining the APM threat landscape, much like the APTs in hacking, requires a holistic, victim-centric approach. Attribution will not be discerned from strictly technical signatures, but through diagnosis of sustained, coordinated behavior in pursuit of specific objectives. The spectrum of APMs is defined by three questions:

· What do they seek to achieve?

· How are they achieving their objectives?

· Who is employing manipulative methods in pursuit of these objectives?

Social media investigations, like cyber security ones before them, face the challenge of account anonymity. The process for tracking, tagging, and ultimately disrupting APMs comes from working in reverse to identify the goal of manipulation, the means of manipulation, and then determining which actors seek and have the means to achieve this manipulation.

Demonstrating how to use this framework, this brief focuses on disinformation efforts by Russia over the last five years. Russia was and is the forerunner in disinformation, but now it is but one of many APMs pursuing their influence objectives via social media. It is matched by other countries and will soon be outpaced by those with the resources and technology to apply more science to their information warfare art.

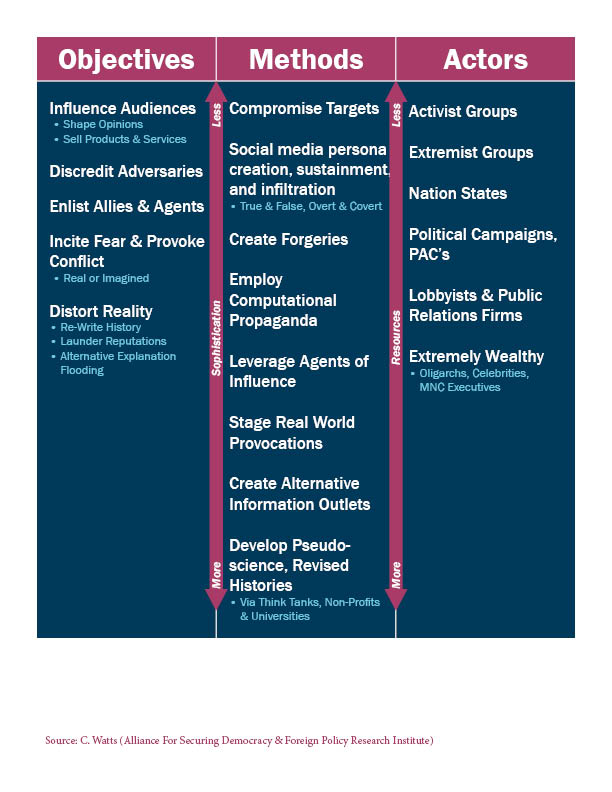

Figure 2

Objectives

Traditionally, the primary objective of social media manipulation has been to influence audiences so as to sell products or services or to shape opinions around a desired agenda or perspective. For example, in 2014 Russia sought to instill in Western discourse the idea that President Bashar al-Assad offered the best counter to terrorists in Syria. A secondary objective of this campaign quickly emerged that aligned closely with its historical record of character assassination. Discrediting adversaries is a hallmark of Russia’s disinformation playbook, but many other actors now exploit social media platforms to undermine support for and the credibility of their detractors, who range from regional experts, academics, media personalities, elected officials, and institutional leaders.

As social media has become an outgrowth of the traditional Internet, it has also offered bad actors a new and highly effective method for enlisting allies and agents. Persona construction, preference selection, group formation, and two-way communication made social media an ideal mechanism for APMs to recruit members, absorb proxies, and engender witting and unwitting people to undertake virtual and physical actions to advance their cause.

Many APMs have accomplished the more basic objectives of influencing audiences, discrediting adversaries, and enlisting allies and agents. The Kremlin has widened its objectives by employing its traditional “active measures” playbook in cyberspace, taking online manipulation to the next level. It has employed specific themes to incite fear and provoke conflict within targeted audiences. Through social media, Russian propagandists have instigated provocations and arranged physical gatherings, stoking conflict between competing groups in the United States. The 2016 Florida flash mob and Texas pro- versus anti-Muslim gatherings offer two frightening examples.

Since the 2016 U.S. presidential election, distorting reality has become a long-term goal of the most sophisticated APMs. Unfiltered cyberspace permits determined, well-resourced actors the ability to re-write history through the modification of crowd knowledge platforms (e.g. Wikipedia) or the creation of alternative data and analysis. Reputation laundering to cleanse the public perception of public figures involves sustained marketing campaigns littered with falsehoods and manipulated truths.

Most damaging to social media platforms and to societies may be the flooding of the information space with alternative explanations. Lacking any concrete evidence and offering conjecture or endless possibilities, Russia has been able to game search-engine algorithms and to manipulate public perceptions of its most heinous acts by showering audiences with so many alternative explanations that the truth cannot be discerned.

Methods: Blending Virtual and Physical

APMs use methods spanning the virtual and physical worlds to achieve their objectives. Physical break-ins to obtain material to compromise targets in the Kremlin’s playbook have been almost completely replaced by cyber intrusions. Hacking will remain a central technique for gaining private information that can later be made public to drive discourse. Russia’s Internet Research Agency troll farm, a manipulation fusion center, will be an example for the more sophisticated current and future APMs. Overt and covert social media persona creation, sustainment, and infiltration into key audiences will require such a coordinating headquarters for advancing a mixture of true and false content for manipulating audiences.

The least sophisticated APMs will struggle to accomplish the more advanced actions that are seen in Russia’s synchronized influence and intelligence operations. Since the days of the Soviet Union, the Kremlin has invested heavily in creating forgeries to drive disinformation. Already today and even more so in the future, manufacturing believable, untraceable digital forgeries (deep fakes) will provide APMs a significant advantage in their disinformation efforts.

Employing computational propaganda will provide an edge to the most powerful APMs. Social bots continually grow in sophistication. APMs will continue to pursue ever-more advanced computational propaganda across platforms in order to incite fear and distort reality in target audiences – the more advanced and coveted objectives of the strongest manipulators.

Since the U.S. presidential election of 2016, analysis of Russian disinformation has been disproportionately focused on technology, while ignoring the important physical dimensions of audience manipulation. Russia’s success comes from leveraging agents of influence to advance its agendas in the virtual and physical worlds. Its unwitting and witting supporters (“useful idiots” and “fellow travelers”), as well as directed agents, advance discussions and influence audiences. Agents of influence also assist, amplify, and in some cases stage physical-world provocations to establish a true or perceived reality that can be advanced on social media. Russia’s intelligence services – from afar in the case of the United States or on the ground in the case of Ukraine, Syria, or even Montenegro – nimbly blend physical-world operations with virtual influence to successfully move audiences to their preferred objectives.

The most resource-intensive and long-term methods seek to generate the basis for sustained influence campaigns. Creating alternative information outlets is essential to powering troll farms and social media pundits. Russia deploys a seamless mix of propaganda via overt state-sponsored outlets and, increasingly, lesser-attributed information outlets that degrade confidence in democratic institutions and truth itself.

The strongest influence campaigns must root their propaganda in what is, or what appears to be, a factual basis. When the truth does not support or suit the objectives of APMs, they will seek to develop pseudo-science and revised histories to advance their narratives. The best-resourced and longest-enduring APMs are developing think tanks, non-profits, lobbying groups, and university programs. These physical front organizations with a virtual presence provide the underpinnings for aggressive propaganda by state-sponsored outlets and troll farms. The Soviet Union used this approach to spread AIDS conspiracies in the 1980s. Today, Russia continues to elevate or leverage agents of influence in sympathetic schools and policy institutions, and to create and fund think tanks to legitimate its views and world standing.

Actors: A Growing Spectrum

Recent discussions about disinformation have overlooked the social media manipulators that came before the Kremlin. Activist groups pioneered the technique of compromising hacks to influence public discourse. The “hacktivist” collective Anonymous breached websites and social media accounts of designated targets, using defacements or spilling secrets to drive negative public perceptions of their targets. Much as with current disinformation peddlers, some applauded and some condemned the actions of such groups depending on the issue or target.

Alongside activist groups, extremist groups took to social media to advertise themselves and to radicalize and recruit supporters through multi-media propaganda. Their forays on Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook have since subsided slightly, but they remain active on smaller, fringe platforms.

Reduced physical connections and lower technological capacity have rendered these forerunners in social media influence less prolific each year. Activist and extremist groups continue to explore and exploit social media to raise awareness and drive their messages but they are the poorest APMs in terms of resources and rely on the enthusiasm and skills of their supporters.

Nation States went from being the victims of social media populism to masters of social media manipulation in about half a decade. Platforms have become tools of domestic oppression for authoritarians and dictators as well as gateways for sowing dissension and chaos among democratic adversaries abroad. Russia adapted its disinformation playbook for the social media era from its Soviet antecedents, and since 2016 Cambodia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Iran, Syria, and likely many others have entered the social media battlefield to advance their interests.

Activists, extremists, and states will remain features of the spectrum of APMs, but the most advanced future ones will be those that have greater resources and access to talent and technology.

Political campaigns and Political Action Committees have aggressively moved to unregulated social media platforms to surgically target audiences in support of their candidates and policy agendas. Political campaigns can command more resources than even some states, and can leverage campaign volunteers and issue-driven enthusiasts to advance an agenda.

Lobbyists and public relations firms have been increasingly revealed as behind-the-scenes architects and backers of social media campaigns. Surreptitious recordings of Cambridge Analytica CEO Alexander Nix showed how online influence and real-world cutouts integrate to smear targets, discredit opponents, manipulate public perception, or drive regulation. Even Facebook has been accused of this kind of manipulation.

The extremely wealthy will increasingly use social media manipulation to increase their influence, expand their “brand,” and suppress their detractors. Oligarchs will hire the best public relations firms, or in some cases simply create or acquire media outlets to advance their causes. They may also create or buy social media and analytics companies. Celebrities will and have employed inauthentic personas, ghostwriters, and amplification tools to expand their influence and to market products.

These will be the most devastating actors as they will be able to purchase or rent advanced technology – artificial intelligence, advanced social bots, and deep fakes – to improve on the existing art of manipulation with the best and latest science.

APM networks can and usually do represent a set of actors pursuing many complementary objectives. They are likely to work, enlist, or employ one another as parts of morphing networks to spread their influence when they share common objectives. Some will largely in-source their operations, similarly to Russia and Iran staffing and funding hacker teams, state-sponsored news services, and social media teams. Other states and public relations firms will opt to outsource their manipulation on an ad hoc basis depending on their objectives. Smaller states, political campaigns, oligarchs, or celebrities will hire individual hackers, ghostwriters, public relations firms, or even full-spectrum manipulators (i.e. trolling-as-a-service firms) to pursue those methods for which they lack technology or manpower.

In all three columns seen in Figure 2 (Objectives, Methods, and Actors), the level of sophistication, resources and required talent increases as one moves from the top to the bottom of the chart. For “objectives,” discrediting adversaries is simpler and generally cheaper than inciting mass fear in a targeted audience. Single hackers, a social media persona, and a timely data dump can inject a discrediting campaign into the mainstream media. Shifting a target audience’s behavior, though, might require months or years and dozens if not hundreds of people to create a propaganda outlet, win audience share, and advance narratives through a social media troll farm.

For “methods,” creating simple digital forgeries is less resource intensive than housing and staffing a bogus think tank equipped with credentialed academics. Activist groups rely on volunteer labor, and the methods they employ are limited to the most talented member of their collective. Conversely, the wealthy can employ the most advanced methods and pursue the most complex objectives their money can buy – whether that is a troll farm, a hacking collective, a news site, an academic center, or all of the above.

Why Social Media Companies Struggle against APMs

The social media giants have taken a beating since the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Most have now dedicated significant resources to the problem of APMs, and some have made advances against them. But social media moderators face a tougher challenge than traditional information security professionals for several reasons.

First, APMs work symbiotically with the physical world to amplify their effects. While hackers operate and perpetrate in cyberspace, APMs stage physical-world provocations, create bogus news outlets, and leverage agents of influence. To date, social media companies appear narrowly focused on the virtual aspects of influence – lacking either the will or the way to more effectively identify the people behind widespread manipulation.

Social media companies struggle not just with the physical-virtual divide, but also with the cross platform nature of APMs. Successfully thwarting APMs requires them to recognize that only a portion of these nefarious activities happens on their platform. APMs use a range of platforms for placement of content, propagation of narratives, saturation of audiences, and hosting of media types. The continued lack of a rapid, near-real-time, industry-wide collaboration among social media companies will result in endless rounds of account takedowns and the pushing of APMs to smaller, lower-resourced, and lesser-policed platforms. Additionally, platforms seem poised for endless legal challenges by those removed and censored. The prevalence of extremist speech on Gab offers one example of the former challenge, and the Manhattan Community Access Corp v. Halleck Supreme Court case evidence of the latter.

Speech is far tougher to police than a breach, and acceptable content varies depending on the time and place where it occurs. A multitude of regimes, regulatory environments, and cultural proclivities result in a mishmash of overlapping terms of service that will be difficult to enforce evenly and objectively. APMs will be able to challenge the platforms relentlessly for their policing, allege bias when regulated, and then make small adjustments and still pursue their goals.

Finally, the erosion of user trust in social media platforms has further accelerated the “balkanization” of the Internet. Mobile phone audiences are increasingly partitioned by their usage of apps, and APMs will seek to move their audiences onto apps of their own design. It is far easier to enlist allies, distort reality, and incite fear if a manipulator can control a user’s information flow through an app. Simultaneously, apps provide APMs unlimited harvesting of the data, communications, and preferences of their users without violating the terms of service of the big social media companies.

The APM spectrum outlined here will evolve in the future, with more actor types emerging and methods being added. New objectives may emerge as well, but for now, tracking APMs via their objectives and methods will better inform social media companies and industry efforts to protect their platforms. This more holistic approach will offer a coherent intelligence-led understanding of the operating environment, comprehensive indicators, and warnings of APM activity. Recognizing the full spectrum of manipulators, rather than focusing on removing single actors from a single social media platform, will illuminate platform-wide policy changes that restore user trust and thwart the full range of current and future APMs.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.