Overview

Throughout President Biden’s first overseas trip as president—one that saw him attend the 47th G7 Summit in the United Kingdom, the 2021 NATO Brussels Summit and EU-U.S. Summit in Belgium, and a tête-à-tête with Russia President Vladimir Putin in Switzerland—Russia and China’s state media and diplomatic mouthpieces worked to paint a picture of a frayed transatlantic relationship that is at once “irrelevant” and “dangerous.” This was particularly evident after the G7, NATO, and EU-U.S. summits produced statements that directly criticized the Russian and Chinese governments’ human rights records and malign influence abroad, which Moscow and Beijing framed as evidence of anti-Chinese/Russian hostility, Western hypocrisy, and Europe and the United States’ antiquated “Cold War mentality.” These narratives are not new, of course, and, given that a stated objective of President Biden’s visit was to convince European allies to “confront the harmful activities of the governments of China and Russia,” they were largely predetermined before Air Force One touched down in England. But while Russia and China’s responses to the summits were predictable, the extent to which the two countries mirrored and at times directly amplified each other’s talking points speaks to an increasing convergence in Beijing and Moscow’s information activities.

By the Numbers

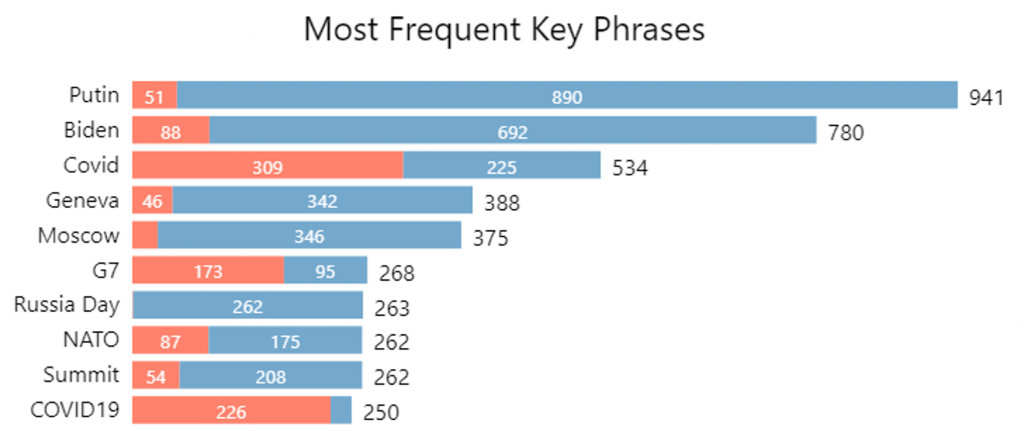

Last week, President Biden’s European sojourns dominated Russian and Chinese state-funded media and diplomatic outputs on Twitter, with the U.S. president trailing only Vladimir Putin in total mentions between June 11 and June 17. While the two countries focused on different parts of Biden’s tour—Russia produced more commentary on the Biden-Putin and NATO summits than the G7 meeting, while the reverse was true of China—the metanarratives were remarkably similar.

Most used key phrases from Russian (represented in blue) and Chinese (represented in red) state media and diplomatic accounts on Twitter from June 11-June 17. Source: Hamilton 2.0.

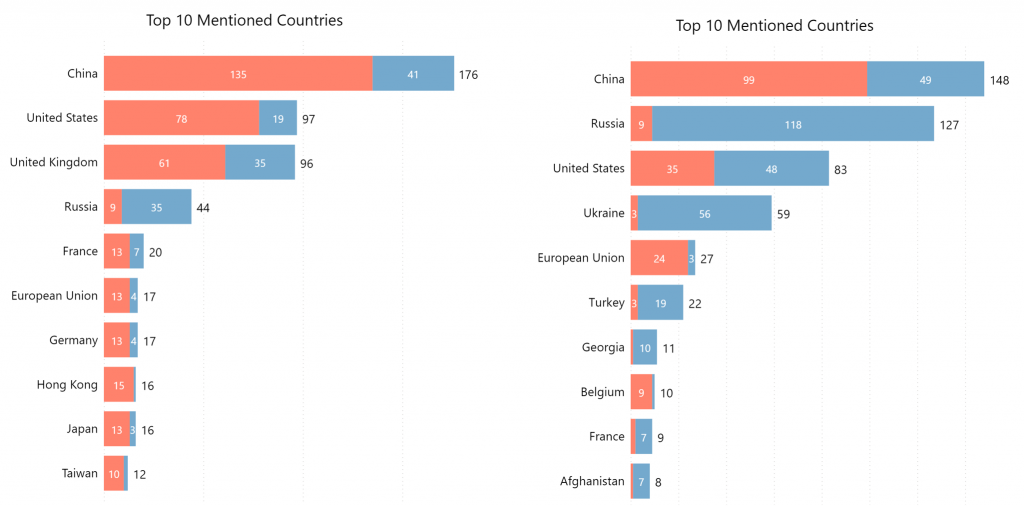

First, both countries attempted to disparage NATO and the G7 as tools for U.S. influence, as evidenced by the fact that the United States was mentioned far more often in NATO and G7-related tweets than other member states, including the United Kingdom and Belgium, which hosted the summits. Second, China and Russia both pushed the notion that the two organizations were mired in Cold War thinking; the term “Cold War” was used in 38 articles (24 Russian state media articles and 14 Chinese state media articles) and 114 tweets (39 Russian tweets and 75 Chinese tweets) that mentioned the G7 or NATO between June 11 and June 17. Third, in G7-related tweets, both China and Russia focused more on Chinese grievances than Russian ones—somewhat surprisingly, Russian diplomatic and state media accounts mentioned China more often than other country, including Russia.

From left to right, the most mentioned countries in Russian (represented in blue) and Chinese (represented in red) state media and diplomatic tweets refencing the G7 (left chart) and NATO (right chart) from June 11-June 17. Source: Hamilton 2.0.

There were, however, key differences, namely in the focus paid to each country’s regional rivals. In NATO and G7-related tweets from Chinese and Russian accounts, over 90 percent of mentions of Ukraine and Georgia came from Russian accounts. China, unsurprisingly, was focused more on Taiwan and Japan, with Chinese outputs accounting for more than 80 percent of the mentions of the two countries.

What We’re Seeing on Hamilton 2.0

In the lead up to Biden’s European trip, Russian state media and diplomats eagerly tracked the movements of the relevant parties and the pomp and circumstance associated with the Biden-Putin meeting. Diplomatic accounts also used specific hashtags for the event, including #GenevaSummit2021, #BidenPutinSummit, #РоссияСША, and #RussiaUS. Coverage often cast the United States as responsible for the poor state of U.S.-Russian relations, a common refrain from Russian officials.

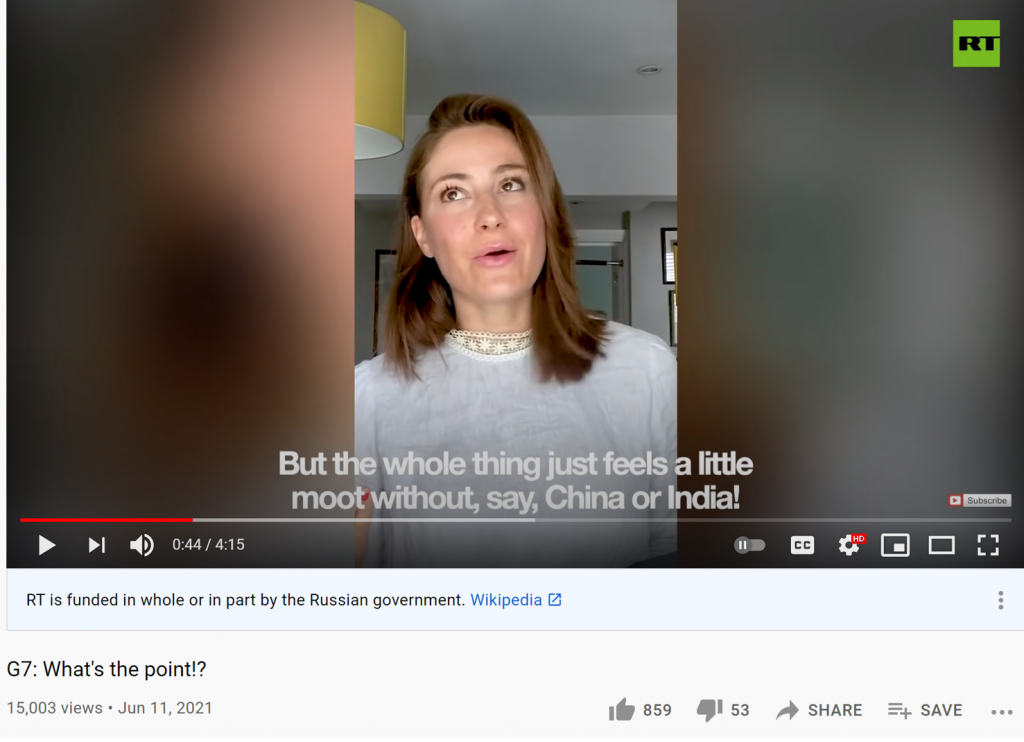

Without a direct role in last week’s meetings, Chinese officials and state media’s primary target was the G7 summit in the United Kingdom. Beijing denigrated the group as “irrelevant” and an “anachronism,” at turns snubbing its nose at the proceedings while simultaneously railing against the elitism of the “small clique” of nations. This was also a favored talking point among Russian state media outlets, which regularly repeated Beijing’s talking points in their G7 coverage. For example, in a video posted to RT’s YouTube channel titled “G7: What’s the Point?” RT, in its typically glib fashion, questioned whether the summit was “moot” without the inclusion of China. (Russia, which was removed from the then-G8 after the annexation of Crimea, was conspicuously not mentioned as an aggrieved party.)

Source: RT

A secondary point of emphasis—particularly from China—was an attempt to frame the group’s non-U.S. members as vassals of the United States. Both state media and Chinese diplomats shared a Chinese cartoonist’s portrayal of the G7’s attendees as colonial apostles at the United States’ last supper. This accompanied attempts to emphasize fissures between the United States and the European Union.

Source: Global Times and the Chinese Consul in Cape Town

Chinese state media also worked to dent the appeal of the G7 countries—the United States in particular—outside the transatlantic space. State media outlet Xinhua featured criticism of the summit from experts from Kenya and Pakistan, and Global Times called on India to cast off any future alliance with the supposedly self-interested United States.

Source: Global Time on India and Global Times on Quad

Unsurprisingly, the most hostile coverage was directed at the G7’s communique about human rights abuses in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, which Beijing characterized as “deliberate slandering,” “meddling,” and evidence of the G7 “ganging up” on China. Once again, Russian state media outlets amplified these claims, often directly quoting China’s official rebuttals. But Chinese officials and state media also directed their ire at the announcement of a major infrastructure plan to rival the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The Chinese network portrayed the plan as, at best, an “empty promise” and, at worst, an “imperialist plan” to harm developing countries.

Sources: Xinhua and Global Times

Coverage of the NATO summit was slightly more subdued, though Russian diplomats and state media, taking cues from Putin’s NBC interview, regurgitated accusations that NATO has an aggressive posture toward Russia (as usual bringing up the claim that NATO promised not to expand) and is a “Cold War relic.” Some commentary also suggested that NATO is just a U.S. tool. Several outlets also cited surveys that showed that global respondents were concerned that the United States is a threat to democracy or viewed the country as a poor example of democracy.

Meanwhile, Beijing’s main response to the NATO summit was to rebut claims of Chinese aggression by contrasting the Alliances’ defense expenditures with those of China. Ministry of Foreign Affairs officials also cited disparities between China and NATO’s nuclear stockpiles, presumably to further the claim that NATO poses the real danger to global security.

Sources: Hua Chunying and Zhao Lijian

Finally, coverage of the Biden-Putin summit, despite significant windup, was less vitriolic than coverage of the week’s other meetings. Russia’s post-summit coverage generally struck a tone of cautious optimism at the outcome, though some content cast the United States as hypocritical or biased in its stances on human rights and foreign interference in elections—key points of contention in the U.S.-Russian relationship. Sputnik and RT both covered former President Trump’s statements criticizing the meeting, while non-English language state media outlets worked hard to manufacture a narrative of widespread American disappointment in Biden’s performance, seemingly relying on anonymous Twitter accounts as their source.

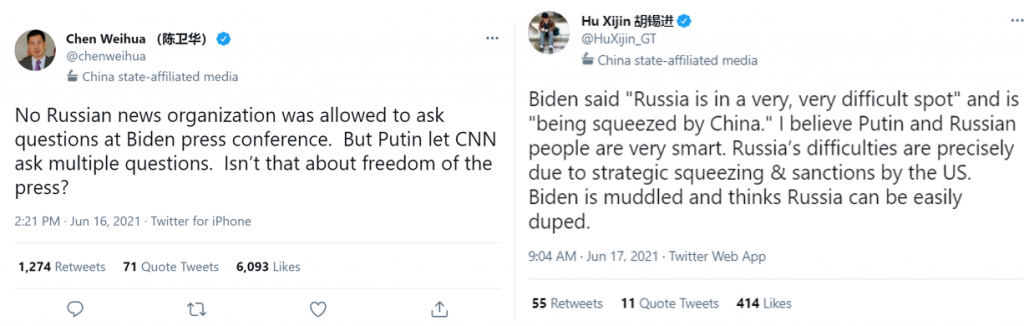

For their part, Chinese diplomats and state media lauded President Putin before the Biden-Putin meeting and stressed the closeness of relations between Beijing and Moscow. While China’s post-summit coverage was largely factual and unbiased, its more bombastic Twitter personalities took swipes at Biden, including suggesting that the differences between Biden and Putin’s respective press conferences were evidence of Putin’s greater respect for press freedoms.

Why It Matters

After a whirlwind week of summits, the clear signal from Washington and European capitals was a consensus that Beijing is, if not a commensurate threat as Moscow, at least a close second. The pushback from Beijing and Moscow was therefore predictable, as were the specific lines of attack. Less predictable was the extent to which Kremlin talking points have become Chinese ones, and vice versa. Although much has been made over the past year about China adopting elements of the Kremlin’s information playbook, the fact they have become each other’s cheerleader, enabler, and amplifier speaks to a different kind of informational convergence—one that likely will have implications for years to come.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.