Overview

President Trump’s executive order last week outlining plans to effectively ban Chinese short-form video app TikTok from the U.S. market triggered a predictable backlash from China’s state media and government officials, who accused the U.S. government of using national security concerns as a false pretext for economic protectionism. Condemnation also came from Moscow, continuing a trend of Russian state-sponsored outlets backing Beijing in tech policy disputes with Washington. Both countries also framed the president’s decision as further evidence of the U.S. government and tech sector’s drift towards authoritarian censorship and surveillance—failing to note, of course, the digital surveillance models employed by the Chinese Communist Party and Kremlin.

By the Numbers

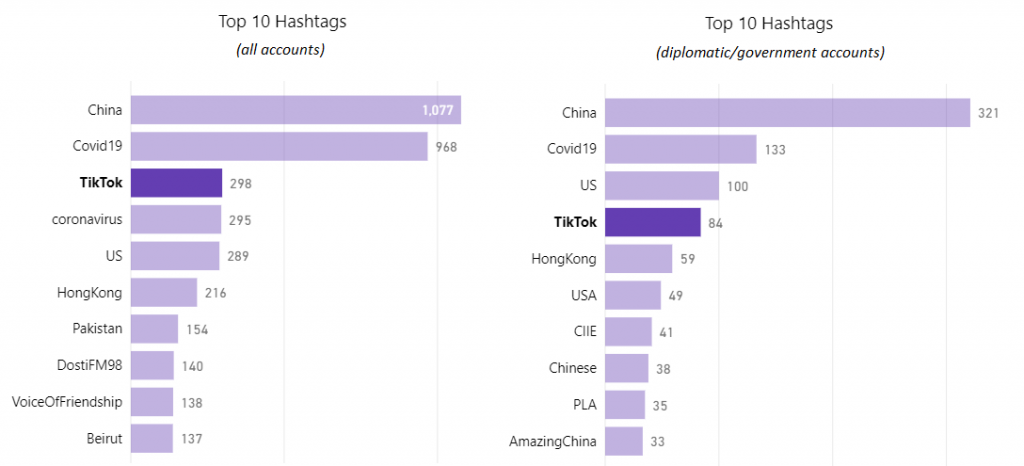

Between August 1 and August 7, #TikTok was the third most-used hashtag by the entire network of Chinese Twitter accounts monitored on Hamilton 2.0, and the fourth most-used by the Chinese diplomatic and government accounts monitored on the dashboard:

Top 10 hashtags used by all Chinese accounts and diplomatic/government accounts monitored on Hamilton 2.0 (August 1-August 7, 2020).

In addition, at least 100 different English-language articles and broadcasts covered the TikTok ban. Those outputs—along with relevant tweets—featured a mix of factual news updates and opinion pieces, the latter of which were, unsurprisingly, universally critical of the Trump administration’s decision.

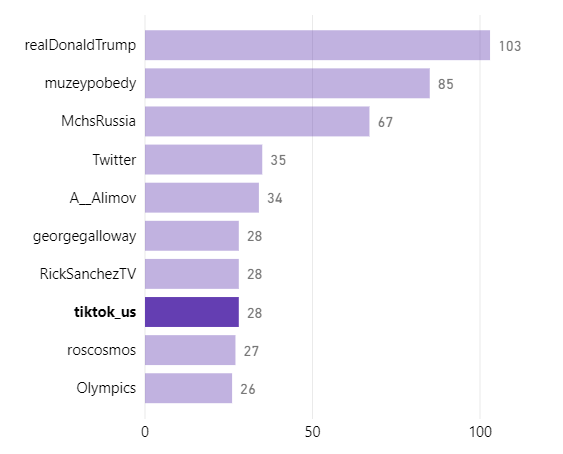

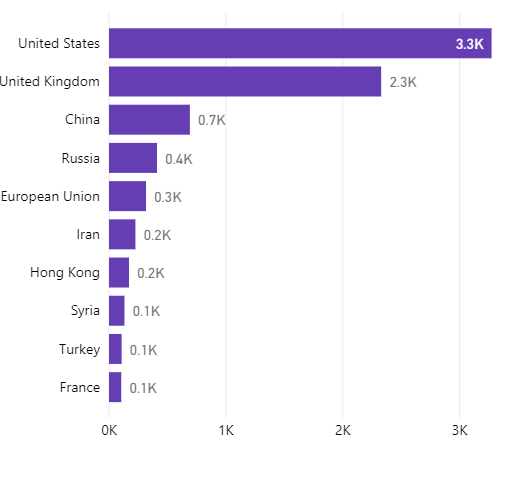

Most mentioned Twitter handles by Russian state-media and government accounts between August 1-August 7, 2020.

While TikTok was not as prevalent in official Russian Twitter outputs, the Chinese social media company was mentioned in 229 tweets and was the eighth most-mentioned handle between August 1 – August 7:

During the same period, Russia’s English-language websites posted 59 different articles mentioning TikTok.

What We’re Seeing on Hamilton 2.0

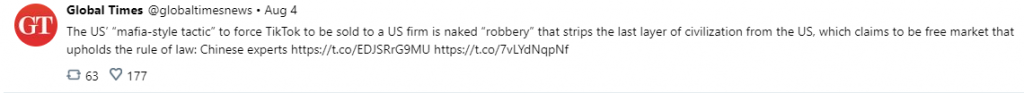

The most salient talking point advanced by Chinese officials and state media was the notion that the United States is using national security as a smokescreen to protect its own economic interests and to solidify its technological “hegemony.” The individual messages often explicitly accused the United States of economic “theft” or “robbery”:

Additionally, state media hinted that the move was timed to benefit Facebook’s newly launched Instagram Reels, which CGTN and Xinhua referred to, respectively, as a TikTok “clone” and “knockoff.” Xinhua tied both narratives together in an article that directly accuses the U.S. government of “bullying” and Facebook of “plagiarism”:

“Facing threats of a U.S. ban and smears by rival Facebook, popular video-sharing app TikTok is compelled to respond to what observers describe as an effort to rip up the Chinese-owned firm and reap their own commercial, political benefits, and monopolize the tech economy.”

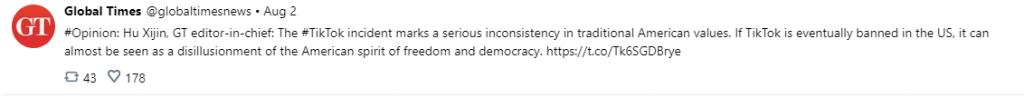

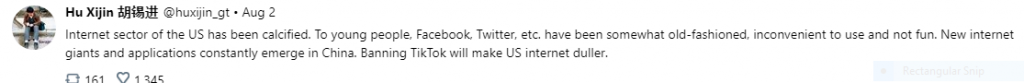

Other prominent narratives were that a U.S. ban would be inconsistent with traditional American values and would make the internet “duller”:

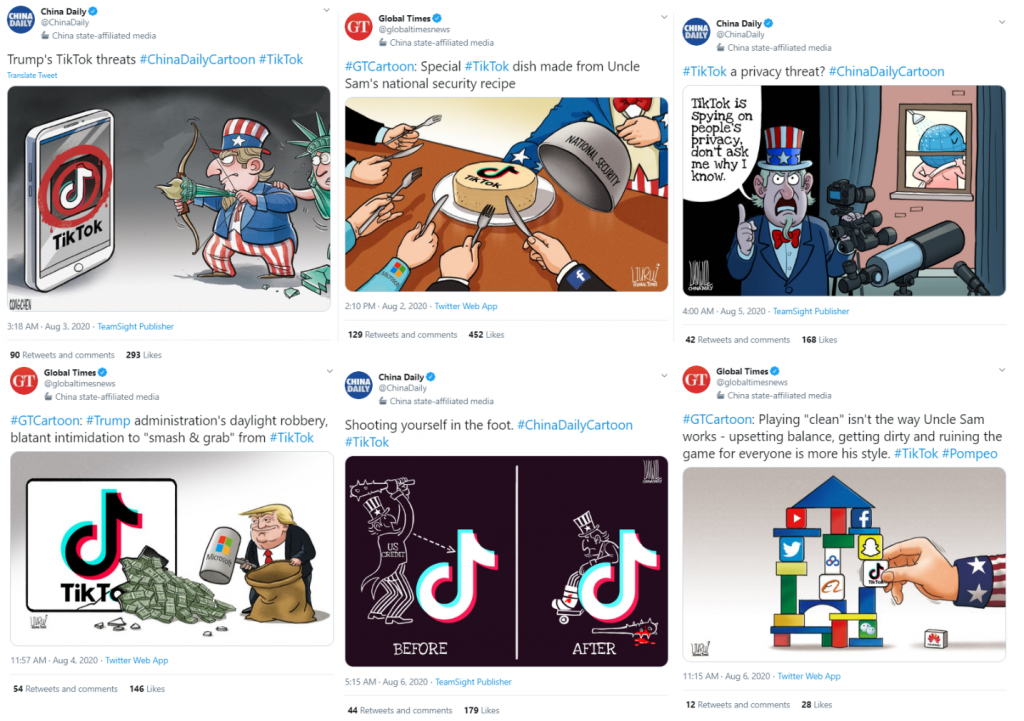

Many of these narratives served as fodder for political cartoons and other visual content, which tend to generate higher engagement numbers on Twitter than more conventional tweets:

Finally, there was a suggestion that the U.S. decision was motivated not by data protection concerns but by the inability of “Five Eye” intelligence agencies to use TikTok data in their own data collection and surveillance efforts. In a CGTN opinion piece, Tom Fowdy, a British academic oft-cited by Chinese state-media, suggests that the real threat TikTok poses to the Western government is that “it denies [them] access to data from their own citizens.”

Along with state media activity, Chinese diplomats and government officials were also vocal in their defense of the viral video app. Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying drew a parallel between TikTok and past instances of litigious American economic maneuvers in France and Japan:

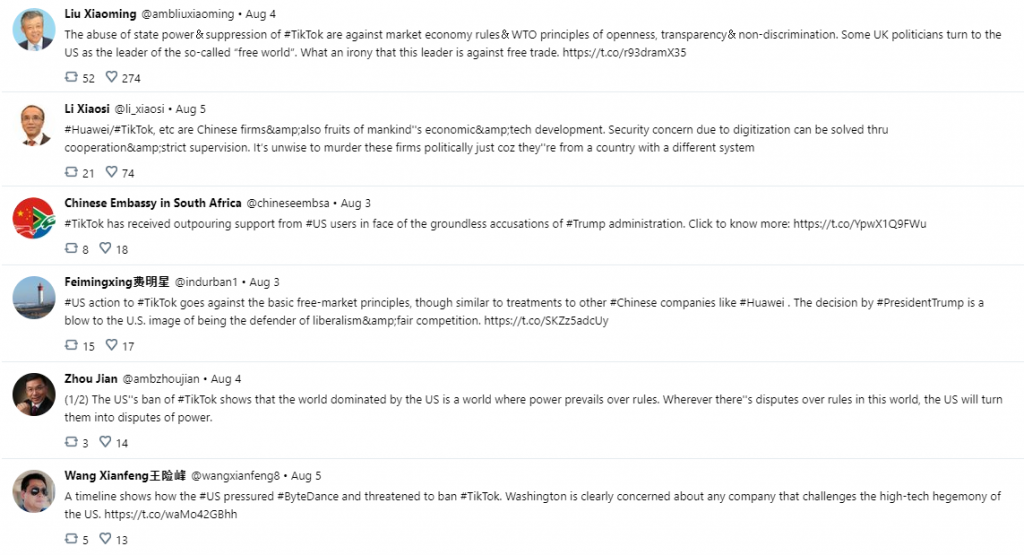

With clear signaling from top Ministry of Foreign Affairs officials, Chinese diplomats rallied around TikTok and denounced alleged U.S. economic imperialism:

The common thread running through all these messages is that the United States is adopting a “might makes right” approach to world affairs, whereas Beijing is attached to “WTO principles,” “cooperation,” and “basic free-market principles.”

Russian state-funded media echoed many of the same narratives as its Chinese counterparts, at times directly quoting Chinese state-media and government talking points:

That Kremlin-funded media would back Beijing in a dispute with Washington is unsurprising. Data from the dashboard shows that Russian media outlets have consistently promoted Beijing’s interests on issues ranging from Huawei to the U.S.-China trade war. RT America and RT UK’s YouTube channels, for example, have published more content focused on China than Russia over the past year:

Top 10 countries associated with RT America and RT UK video content from July 9, 2019 – August 10, 2020.

Additionally, Russia’s state-backed English-language media outlets have long focused on real and perceived problems in the U.s. tech sector to allege censorship of U.S. conservatives, privacy abuses, and Orweillian (Western) government control of the internet. The Trump administration’s move to ban TikTok is thus a continuation of those critcisms; though, obviously some are more relevant than others.

Why It Matters

Since TikTok took the internet by storm in 2018, the national security community, in the United States and beyond, has voiced concerns about the viral video app. With a parent company, ByteDance, based in Beijing where companies are under a legal obligation to hand over user data when so required by the authorities, TikTok’s prospects in democratic countries have been further damaged by convincing claims that it censors topics deemed unacceptable by the Chinese Communist Party.

Despite these legitimate concerns, Chinese and, to a lesser degree, Russian state-funded media’s criticisms of the TikTok ban are likely to resonate with many audiences—particularly those outside the United States. The Trump administration thus faces an uphill climb—in part due to its own inconsistent messaging—to convince both domestic and foreign publics that security concerns rather than economic interests motivated the TikTok ban.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.