Introduction

Prior to the war in Ukraine, Russia was perceived to be an unrivaled power in the information domain, and its ability to conduct sophisticated information operations was considered a distinct strategic advantage in the event of a war. But Russia’s propagandists struggled to control the narrative in the early weeks of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, underestimating the mettle of Ukraine’s army, the skill of its communications professionals, and the resolve of Western companies and governments to shut down or restrict its media outlets. A week after Russia’s invasion, observers were already declaring that “Ukraine is winning the information war”.

A year into the war, Russia’s propaganda apparatus has not recovered from its initial setbacks. Despite their efforts to expand to new platforms and regions, state-backed media outlets have maintained only a fraction of their pre-war audiences, and support for Russia, at least among publics providing material and financial support to Ukraine, remains exceptionally low.

While the Kremlin continues to lose the information war—at least in the Global North—it has not lost the ability to use information operations in the pursuit of its strategic objectives. To that end, Russia’s information strategy in Europe and the United States has shifted from one focused on painting its actions as necessary, to one focused on highlighting the real costs of the war on the West. This recalibration is in keeping with Russia’s broader information strategy. Russia has found success in its influence operations in the past not by rallying audiences to its cause, but by turning them away from the causes of others. The Kremlin need not win hearts and minds to achieve its desired aims; it need only convince Ukraine’s backers that the price of their continued support is too high.

Perhaps most alarmingly for Western observers, China has continued to provide rhetorical cover for the Kremlin, all while still maintaining its stance that it’s a neutral stakeholder. With the prospect of greater Sino-Russian military cooperation on the horizon, China’s ability to use its own global influence network to undermine the West—particularly in the Global South—remains a significant cause for concern.

This paper analyzes the state of Russia’s influence campaigns vis-à-vis the war to understand the failures, successes, limitations, and potential of Russian, and pro-Russian, information operations to influence the future trajectory of the conflict. It primarily focuses on Russian and Chinese messaging over the first 11 months of the war (February 24, 2022–January 23, 2023) using data sourced from the Alliance for Securing Democracy at GMF’s Hamilton 2.0 dashboard, which tracks more than 700 Twitter accounts and 25 state-backed media outlets belonging to individuals or entities connected to Russian and Chinese government entities or state-funded media outlets. This report also draws from data obtained through CrowdTangle, a Facebook-owned social media monitoring platform.

Importantly, this paper only covers overt messaging, meaning that notable instances of disinformation from covert or gray propaganda sites were not analyzed. In addition, the report focuses on Russia’s, and to a lesser degree China’s, external rather than domestic propaganda efforts.

Russia’s Pre- and Post-Invasion Information Failures

In the weeks before Russia launched its unprovoked war in Ukraine, Russian officials and state media mocked Western warnings about an imminent attack, calling the claims a product of Western media “hysteria”, “fake news”, and a “thesis…born within the walls of the State Department”. As late as February 20, 2022, Russian Ambassador to the United States Anatoly Antonov flatly denied that Russia planned to invade its neighbor, telling CBS’s Face the Nation that “there is no invasion, and there [are] no such plans”. Four days later, Russian troops crossed the border into Ukraine, an act that proved difficult to reconcile with Russia’s earlier denials, not only for Russian government officials but also for Kremlin-funded media figures in the West, many of whom branded themselves as “anti-war” and “anti-imperialists”. A wave of resignations followed, as several of Russian state media’s key American and European personalities, out of genuine opposition or career self-interest, sought to distance themselves from Russia’s war.

This exodus hobbled the Kremlin’s ability to influence foreign publics on social media. Despite the success of some official state media accounts, Russia’s real ability to influence Western audiences had long been achieved through its network of affiliated and loosely affiliated pundits, influencers, and validators on social media. Losing a large chunk of that audience—in some cases in embarrassing fashion—was a significant blow.

But the biggest setback came in the weeks after the invasion, when Russian state-funded media was banned by the European Union and restricted by social media platforms, satellite providers, and digital services companies. Those moves reshaped the Russian propaganda ecosystem overnight. Large and well-established Twitter accounts and Facebook pages lost reach, rebranded, and in some cases disappeared. In March 2022, RT America, the US arm of RT, stopped production and laid off its entire staff.

The EU ban has had a major and lasting impact. In January 2023, RT France announced it would shut down after months of being squeezed by regulators. (As of this writing, RT France continues to publish new content on its website and its social media accounts remain active.) Sputnik France went from generating 166,000 total Facebook interactions in February 2022 to none between April and June 2022, when it effectively stopped posting to the platform. When it began posting again over the summer, it had partially rebranded as Sputnik Afrique, which helped it partially rebuild via new audiences outside the EU. RT Deutsch did not rebrand or rebound. At the start of the war, it was the fourth most popular Russian state media page on Facebook, generating 1,190,000 interactions in February 2022. The next month, it had around 22,000 interactions, making it the 26th most popular Russian state media page. It has not regained its following.

Accounts focused on audiences beyond the EU also struggled. RT en Español, the most influential Russian state media account on Twitter, saw a surge in retweets at the start of the war but has since seen a steady decrease in engagements. In March 2022, RT en Español had 611,000 retweets. That number fell 37% the next month to 386,100 retweets. From June to December, it never received more than 200,000 retweets in a single month. RT saw a similar drop. In March 2022, RT had more than 350,000 retweets. For the rest of 2022, it averaged only 106,000 retweets a month. This downward trend extended to nearly all major Russian state media accounts.

Russia’s inability to control the narrative in the first months of the war was also a result of several self-inflicted wounds. First, the Kremlin’s explicit demand that Russian media avoid calling the war a “war” meant that Russian propagandists were forced to justify something that, according to government’s official line, did not exist. This did more than merely harm Moscow’s credibility outside its borders; it kept Moscow from building a convincing case for the need for war. Second, Russia’s attempts to establish casus belli were muddled by the bewildering decision by President Vladimir Putin to assert that the “special military operation” was necessary to “denazify and demilitarize Ukraine”. This rationale was roundly debunked and ridiculed by outside observers, in no small part because Ukraine is led by a Jewish president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy. The focus on neo-Nazism also shifted attention away from the Kremlin’s most effective, albeit equally disingenuous, argument: That the war was necessary to protect Russian security interests from the alleged threat of NATO enlargement and Western aggression.

Kremlin-backed messengers also proved unable to spin the horrors of war. Thirteen days into the conflict, a Russian airstrike struck a maternity ward in Mariupol, resulting in multiple deaths and images of injured pregnant women. Russian diplomatic accounts smeared one of the victims, claiming she was a crisis actor in “some very realistic makeup”. State media turned to a fake fact-checking site, called War on Fakes, to back up its disinformation campaign. Russia’s narratives around the maternity ward bombing were quickly debunked. Independent outlets and fact checkers also rapidly disproved Russia’s claims that the March 2022 mass murder of Ukrainian civilians in Bucha was faked. Kremlin-linked accounts had made competing claims that the bodies found in Bucha were actors and that Ukrainian forces had carried out the killings. In January 2023, ten months after the war crimes were revealed, Russian diplomats were still turning to Twitter to try to convince the world that Russian troops weren’t involved in the massacre.

Despite these messaging missteps, Russia’s failure to rally Western support for–or, perhaps more accurately, weaken Western opposition to–its war effort needs to be viewed more as a reflection of the limits rather than the failures of Russian information operations. Put simply, Russia’s propagandists have run up against an age-old truism: Good propaganda cannot overcome bad policy, especially when that policy is so nakedly unjust and unnecessary.

A Shift in Strategy

Over the course of the war, Russia’s information strategy in Europe and the United States has subtly but discernibly moved from a defense of Russia’s actions to criticism of the real and potential impacts of the West’s response. By shifting the focus from whether Russia’s actions are justified to whether the West’s support for Ukraine is too costly or too risky, Kremlin-linked messengers have found more solid footing with external audiences—at least as measured by the injection of those narratives into legitimate domestic debates. Prior to the US midterm election, for example, roughly 90% of the most retweeted tweets by Republican congressional candidates that mentioned Ukraine were critical of continued US support for Ukraine. This does not necessarily mean, of course, that those opposed to aiding Ukraine were influenced by Russian messaging, but it does suggest that Russian messaging has found more fertile ground playing to pocketbook concerns rather than historical and geopolitical grievances.

This shift is borne out in the data. In the first six months of the war (February–July 2022), Russia-linked accounts on Twitter mentioned “Nazi” in more than 5,800 tweets.1 In the following six months (August 2022–January 2023), the number of “Nazi” tweets dropped to 3,373—a 42% decline. Mentions of NATO by Russian-linked accounts on Twitter dropped by roughly 30% during the same periods. At the same time, tweets mentioning both “energy” and “Ukraine” increased by 267%, while tweets mentioning “cost of living” increased 66% when comparing February–July 2022 to August 2022–January 2023.

Energy threats in particular have become central to Russia’s wartime messaging. Russia has coupled its decision to cut gas and oil supplies to Europe with a consistent and high-volume information campaign meant to hollow out public support for EU sanctions placed on Moscow’s energy sector. Putin has called Western restrictions of Russian energy “utterly stupid” and self-defeating. State media has shown fights breaking out at French gas stations, Spanish truckers blocking roads in protest of high energy prices, hundreds taking to the streets in the United Kingdom, and European citizens enduring blackouts, cold showers, and dimmed street lights. Kremlin-backed media has framed Russian energy as Europe’s only option and shown European states scrambling for insufficient and environmentally harmful alternatives. State media outlets have also asserted that the United States is profiting off Europe’s demand for energy by selling the continent more expensive US natural gas. At the same time, Moscow-funded outlets have shown Russia selling record amounts of gas, coal, and oil to China and increasing gas shipments to countries in Africa.

Russia’s propaganda campaign around energy has been constant and far-reaching. Through 11 months of war, Russian state media and diplomatic accounts tweeted, retweeted, or quote tweeted around 50,000 posts mentioning “energy”, “gas”, “oil”, or “sanctions”. Those posts generated more than 2,700,000 likes and 950,000 retweets. Following Russia itself, the five most mentioned in those tweets were the United States, the EU, Ukraine, Germany, and China. Russia’s Embassy in the United Kingdom had more success with its energy war propaganda than all but two state media accounts, highlighting the importance of diplomatic messengers in this information campaign. Russia’s Embassy in Japan was also among the five most retweeted accounts pushing energy-related narratives.

The explosion of the Nord Stream pipelines, which carry gas from Russia to Europe, marked a flashpoint in Russia’s energy propaganda. Soon after the September 26 blasts, Kremlin-linked accounts began to blame the United States and the United Kingdom. Russian officials, state media, and intelligence-linked sites argued that Washington had stated its intent to destroy the pipelines, put military equipment in place to do so, and then launched the attacks to weaken Russia and control Europe’s energy market. Partisan commentators in the United States promoted Moscow’s talking points, which were in turn amplified by Russian-affiliated media pundits. Tweets mentioning “Nord Stream” by Russian diplomats and state media generated more retweets and likes in the week after the blasts than they did in the 214 days of war that led up to the explosions. Four months after the pipelines ruptured, Russia’s tweets about Nord Stream brought in more than 89,000 likes and 38,000 retweets.

While the energy war has been a major focus, Kremlin-linked accounts also have sought to shape narratives around other interconnected economic effects of the conflict in Ukraine. Propagandists argued that Western sanctions weren’t impacting Russia’s economy but instead were prompting a global food crisis and driving up inflation, unemployment, and inequality around the world. Putin asserted that Western leaders didn’t “think about how to improve the lives of their citizens”. Grocery store shelves around the West were shown empty. During the first 11 months of the war, Kremlin-affiliated accounts tweeted the terms “inflation”, “recession”, “economy”, or “economic” more than 15,500 times, generating more than 905,000 likes and 313,000 retweets.

The Long Tail of Kremlin Conspiracy Theories

As with prior Russian information campaigns around the downing of Malaysia Airlines flight 17 over eastern Ukraine and the poisoning of Sergei Skripal in the United Kingdom, Kremlin-linked messengers have also turned to conspiracy narratives to muddy the information waters. In early March, Russia’s Defense Ministry began pushing a conspiracy about US-backed bioweapon laboratories in Ukraine. Kremlin-linked messengers claimed that the labs were handling “especially dangerous pathogens” (including the coronavirus), that they were trying to make bioagents capable of targeting certain ethnic groups, and that they were training birds to deliver bioweapons to Russian controlled territories. US commentators, including Tucker Carlson at Fox News, amplified the conspiracy. That success prompted Russian propagandists to build on the conspiracy narrative throughout 2022. Eventually, the Kremlin tied the biolabs to Hunter Biden, the Democratic Party, a range of US government agencies, Germany, Poland, Pfizer, Moderna, and a host of other individuals and organizations.

Through 11 months of war, Kremlin-linked accounts have tweeted, retweeted, or quote tweeted the terms “biological” or “bioweapon” more than 3,000 times. Tweets by Russian accounts containing those phrases brought in more than 161,000 retweets and 311,000 likes. China, which supported the Kremlin’s claims, was the fourth most frequently mentioned country in tweets by Russian propagandists that mentioned the conspiracy—following only the United States, Ukraine, and Russia.

The Search for New Audiences

Russia’s need to adjust its message coincided with a need for new audiences—or at least new ways to reach old audiences—to compensate for government bans and platform restrictions. To reconnect with Western audiences, Russian state media created and aggressively promoted accounts on a range of alternative and lightly moderated platforms, including Gab, Odyssey, and Rumble. Though audiences on those platforms remain small compared to the social media giants, RT’s strategy is clearly to flood the zone from as many different sites as possible, including those credible news outlets consider to be too toxic to host their content. RT has also cynically framed its move to alternative platforms as an effort to “fight censorship”—a ludicrous claim from an outlet funded by a government that has systematically destroyed press freedoms at home.

Despite restrictions, Russian state media outlets have also found creative ways to reach audiences on mainstream platforms. This has largely been achieved through accounts operated by contributors to state media outlets, who, even when labeled as state-affiliated media, do not face the same restrictions as official accounts, particularly in the EU. From July 1 to December 31, 2022, seven of the ten fastest growing state media Twitter accounts belonged to editors, hosts, and journalists working for Kremlin-funded outlets. During that six-month timeframe, Wyatt Reed, a Sputnik writer, gained more than 20,000 followers. Three state media contributors were among the ten most retweeted Russian media accounts in the final six months of 2022, with RT en Español contributor Helena Villar’s account receiving more retweets than Tass, RIA Novosti, and RT Arabic.

State media also created or reactivated accounts affiliated with individual programs. Ahí les Va, an RT en Español-affiliated account, revived a dormant Facebook page in February 2022 and set up a new Twitter account in April. On Facebook, it was the fastest growing state media page each month from April to November 2022. Other new outlets also popped up, including RT India and RT Balkan, the latter of which took Ahí les Va’s spot as the fastest growing Russian state media page on Facebook in December. Though these outlets and accounts have been unable to replicate the reach of RT’s more established channels, the sustained focus on the Global South has seemingly paid some dividends judging by the sharp divides in public opinion and government responses to Russian aggression between the Global South and North.

In the early months of the war, diplomatic accounts also stepped in to fill the messaging gap caused by restrictions on state media, though most diplomats have been unable to maintain a high level of engagement. On Twitter, Russia’s Japanese Embassy went from receiving around 4,500 retweets in January 2022 to more than 101,000 retweets in March 2022. Its numbers have fallen each month since, and in December 2022, it only generated 14,000 retweets. Russia’s Embassy in the United Kingdom had a similar rise and steady decline. Both of those accounts were at the forefront of the bioweapons disinformation campaign, which peaked in the first months of the war.

As Russia’s propaganda apparatus reordered itself to deal with new restrictions, state media and diplomats looked to other groups for narrative support, most notably Chinese propagandists. In the first 11 months of the war, Kremlin-linked accounts tweeted the terms “China”, “Chinese”, or “Beijing” more than 20,000 times. China was the fifth most mentioned country or special territory—behind Russia, Ukraine, the United States, and the European Union. Coverage of China in Russian state media was almost universally positive and regularly parroted Chinese talking points about Xinjiang, “zero Covid” policies, and alleged Western hypocrisy on human rights. In return, Chinese diplomats and state-affiliated media provided rhetorical support for Russia—including signal boosting pro-Kremlin disinformation campaigns.

The Role of China

Beijing’s official position on the war is that it is a neutral party that respects the “sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations”. While Chinese officials and state media are cautious not to publicly endorse Russia’s war of choice, they have, with few exceptions, openly supported and promoted Kremlin-friendly narratives about the war. In the immediate aftermath of the invasion, Chinese state media outlets adopted Russia’s sanitized language to describe the war, obfuscating the severity of Moscow’s actions by labelling the invasion as a “special operation”, an “issue”, or a “situation”. Mentions of “war” or “invasion” were largely reserved for whataboutism arguments directed at past US wars and interventions, most notably in the Middle East. In the first 11 months of the war in Ukraine, the largest war in Europe since World War II, Chinese diplomatic and state-affiliated media accounts on Twitter mentioned the United States more than twice as often as Russia in tweets mentioning “war”.

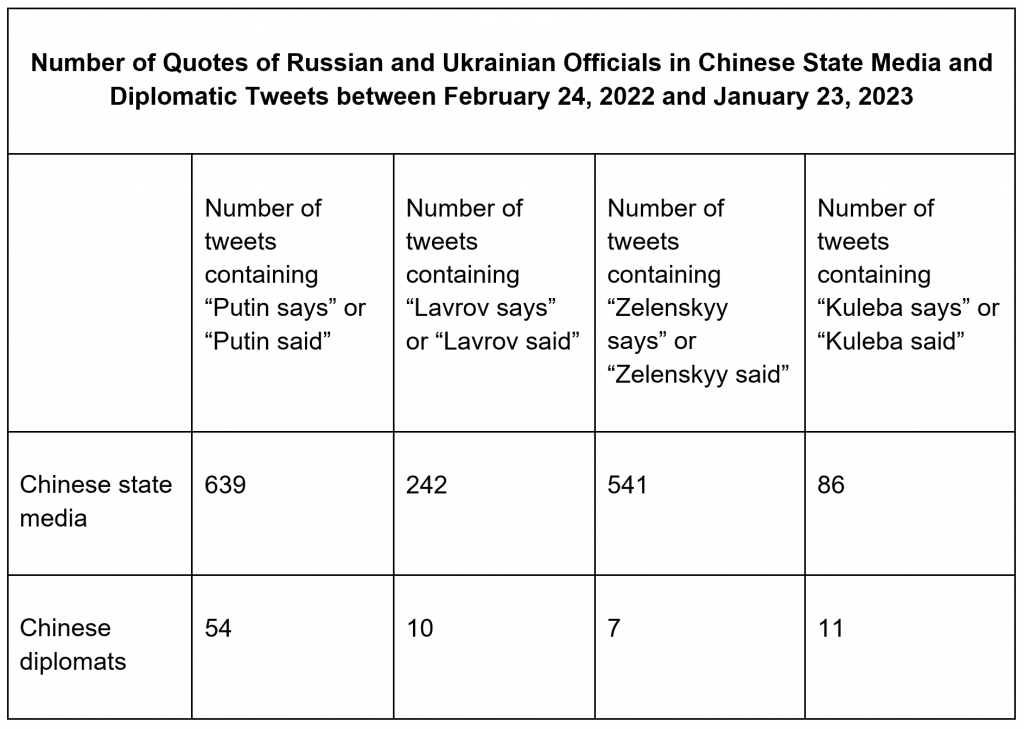

China has also given far more prominence to Russian voices than to Ukrainian ones in its coverage of the war. Between February 24, 2022 and January 23, 2023, Chinese diplomatic and state media accounts on Twitter quoted Russia’s foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, more than three times as often as his Ukrainian counterpart, Dmytro Kuleba. Putin also was quoted more often than Zelenskyy, with Chinese diplomats roughly eight times more likely to quote Russia’s president than Ukraine’s.

Source: Hamilton 2.0

Chinese state media has also provided regular airtime to current and former Russian state media commentators. For example, former UK politician George Galloway, who hosts a show on Sputnik radio and is a regular on RT and RT UK, consistently has been retweeted, cited, and interviewed on Chinese state media during the war. His affiliation with Russian state media is never mentioned. Similarly, Lee Camp, a former host on the now-defunct RT America, was retweeted by Chinese state media and diplomats nearly 60 times in the first 11 months of the war. This signal boost has allowed pro-Kremlin voices to reach an even wider global audience given that Chinese state media pages have over 1 billion followers on Facebook—roughly ten times the total followers of Russian state media pages.

Promotion of Pro-Kremlin Narratives

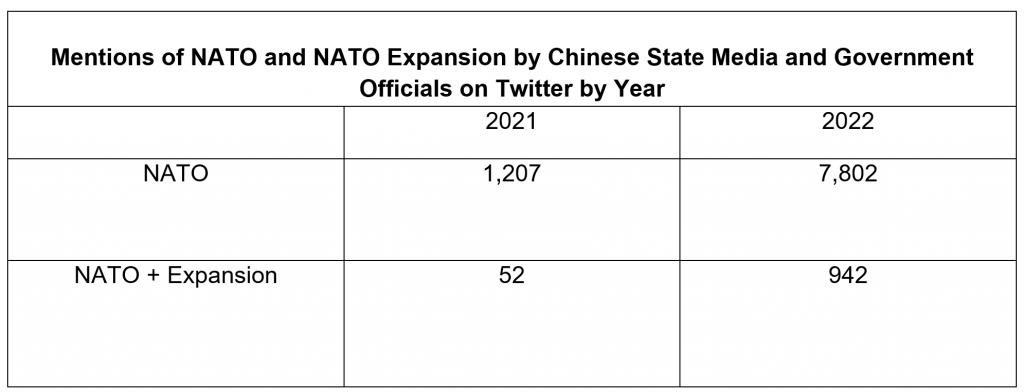

Since the start of the war, the most prominent theme in China’s editorialized coverage of the conflict has been the advancement of anti-US and anti-NATO narratives. While anti-Americanism has been a staple of Chinese state media and diplomatic outputs for the past several years, NATO was not a regular feature of Chinese attacks prior to the war. In 2021, Chinese state media and diplomatic accounts on Twitter mentioned “NATO” in just over 1,200 tweets, with “NATO” and “expansion” referenced in only 52 tweets. Those totals ballooned in 2022, with mentions of the two terms increasing by more than 540% and 1,700%, respectively.

Source: Hamilton 2.0

While mentions of NATO likely increased in almost all global media outlets and government communiques in 2022, the pervasively negative coverage of the organization appeared calibrated to serve Moscow’s, and China’s, interests. Of the 50 most retweeted tweets from Chinese diplomats and state media accounts mentioning “NATO”, all were critical of the organization. The messages were often not subtle. Among the most retweeted and liked posts was a cartoon featuring children pushing a NATO-branded dumpster filled with weapons off a cliff.

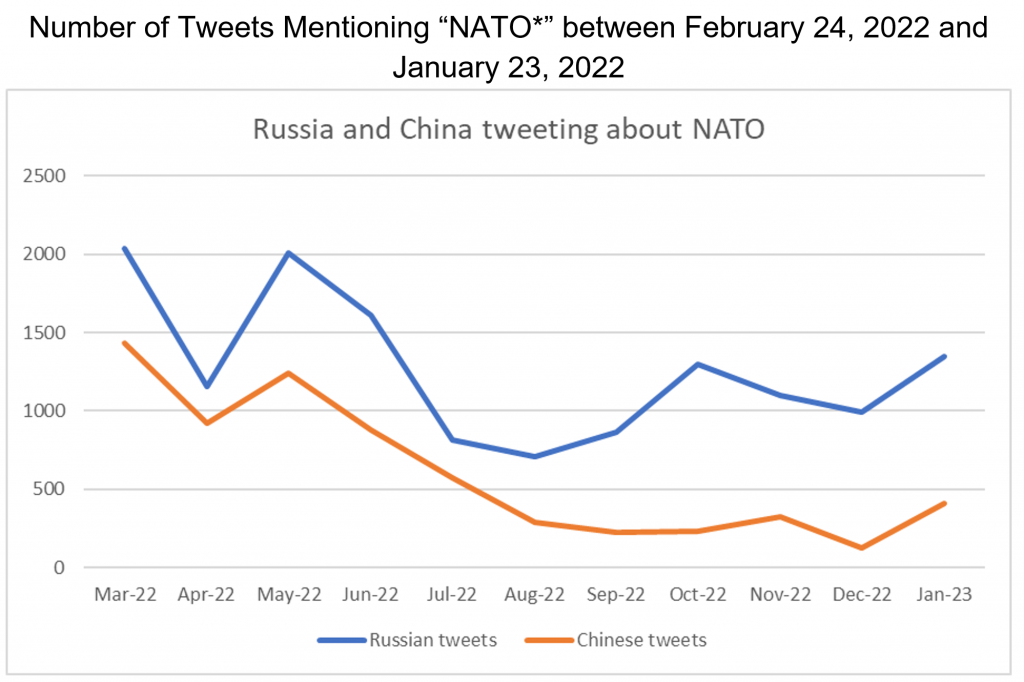

Comparing mentions of “NATO” in Russian and Chinese tweets between February 24, 2022 and January 23, 2023, shows a pattern of China mirroring Russia’s focus on the alliance, though with less intensity. Both countries’ NATO-related messaging spiked in May 2022, when Sweden and Finland applied for membership, and noticeably dipped around August/September 2022 before rising again in late December. This is undoubtedly driven in part by news events, but the strong correlation between the two hints, at a minimum, at a shared desire to attack the credibility of the alliance at key inflection points.

Source: Hamilton 2.0

China’s increased focus on NATO during the course of the war is likely driven in part by increased tensions between the alliance and Beijing; however, China was only the sixth most mentioned country in posts mentioning NATO, and of the 50 most engaged-with tweets about NATO posted by Chinese diplomats, only 5 mentioned China, and four of those were in reference to the accidental bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade during the war in the former Yugoslavia. But China’s attempts to redirect blame for the invasion to NATO and the United States is not merely an altruistic effort to provide rhetorical cover for Russia. By trying to foster division in the transatlantic alliance, China is working to erode the influence of Western democracies on the global stage. This plays into Beijing’s longstanding narratives about the decline of the Western democracies-led rules-based order and the corresponding ascent of an alternative system built around China and its autocratic priorities.

Beijing has also used Ukraine-related messaging to attempt to create fissures in the transatlantic alliance—a clear foreign policy goal for the Chinese Communist Party. Throughout the past year, Chinese diplomats and state media have consistently portrayed the United States as a war profiteer and sought to stress the hardships that European countries were enduring, supposedly for the sole benefit of their ally. This has included regular coverage of European protests of sanctions on Russia; sanctions are portrayed as being driven by the United States.

To weaken Western democracies and their allies, China also has tried to isolate those countries by appealing to the Global South. In the context of the war in Ukraine, Chinese messaging has consistently argued that countries supporting Ukraine are hypocrites and indifferent to the rest of the world, notably by amplifying voices critical of Western hegemony. In addition, even though a large majority of countries condemned the Russian invasion at the United Nations, Chinese diplomats and state media regularly portray Ukraine’s supporters as a minority on the global stage.

Amplification of Biolab Disinformation

The opportunistic dimension of China’s support for its Russian ally in the information space is further evidenced by China’s sustained amplification of disinformation about US-backed biolabs in Ukraine. Diplomats from Asia to Africa and Europe, supported by China’s full arsenal of global state media outlets, have actively promoted the Kremlin’s claim that the United States is running more than 30 bioweapons labs in Ukraine. During the first 11 months of the war, Chinese officials and state media outlets mentioned “lab” and “Ukraine” in more than 500 tweets. This was not merely a spike event; Chinese diplomats have posted about US biolabs in Ukraine as recently as February 22, 2023.

China’s repeated amplification of Kremlin-backed biolab disinformation follows a years-long campaign by Chinese official sources to spread similar false claims about US bioresearch labs being responsible for the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus. These two disinformation campaigns are therefore mutually reinforcing and mutually beneficial, with Chinese sources at times explicitly linking the two. It is yet more evidence that China is most forcefully engaged with topics related to Ukraine that reinforce its own pre-existing narratives and benefit its long-term strategic objectives.

Limits to the “No Limits” Partnership

Chinese messaging around the war in Ukraine has prioritized defending China’s interests over Russia’s; though, both countries’ interests are so strongly intertwined, at least in terms of undermining the West, that it is often difficult to distinguish between the two. However, there are some topics on which China has shown a clear unwillingness to lend its full rhetorical support to Russia. This is most visible in cases where Russian troops have committed or been accused of atrocities and war crimes. For instance, while a few of China’s more confrontational “wolf warrior” diplomats did retweet some conspiratorial content casting doubt on Russian atrocities in Bucha, those posts were anomalies—especially compared to China’s full-throated support of biolabs conspiracies. Instead, China charted a middle course, calling for an independent investigation, while neither denouncing nor defending Russia.

But perhaps the largest third rail in Chinese messaging about Ukraine has been even the suggestion of parallels between Ukraine and Taiwan. On February 25, 2022, the day after the start of the war, China’s ambassador to Cuba reacted angrily to a suggestion from a netizen that NATO might chose defending Taiwan over Ukraine, shouting, “Taiwan is not Ukraine”! In the first 11 months of the war, monitored Chinese accounts mentioned “Ukraine” and “Taiwan” in the same tweet more than 500 times, consistently pushing back against comparisons between the two countries, even when that meant highlighting the illegality of Russia’s invasion. Russia’s decision in September to hold illegal referendums in four occupied territories of Ukraine was also rebuked—albeit artfully—by Chinese officials, who reiterated their commitment to maintaining “sovereignty and territorial integrity”. As the war moves into year two, the “Taiwan question” is likely to continue to be a thorn in Beijing’s side, as evidenced by a post made on February 22, 2023 by Chen Weihua, China Daily’s EU bureau chief, in which he tweeted, “The US/NATO made a huge mistake by linking Ukraine situation with Taiwan. They now hope China to be on their side to help them prevent China’s ultimate national reunification? TW is part of China while Ukraine is a country, that is just int’l consensus. No comparison of the two.”

Conclusion

One year into the war in Ukraine, there is no real prospect in both the near and long term of Russia convincing European and American publics that their war is necessary and just—a fact that Moscow’s messengers have seemed to tacitly acknowledge. But Russia’s information strategy has never been built on traditional tenets of soft power and public diplomacy—that is, an effort to influence foreign publics through attraction and persuasion rather the coercion. Russia has succeeded in the information domain precisely because it is coercive; it drives wedges between its adversaries, corrupts democratic debate, and inflames tensions among foreign publics. If the war in Ukraine becomes a war of attrition, Moscow is simply banking on its ability to degrade support for Ukraine among its staunchest allies. This is reflected in its messaging approach, which, over the course of the last year, increasingly has focused on highlighting the negative externalities of the war in Western societies. Russia has seemingly found some success with this tactic, though observers should be cautious about attributing changes in public support for Ukraine to malign Russian influence.

As the war moves into its next phase, the role of China—both in the information domain and beyond—is also likely to become increasingly important, especially in terms of influencing attitudes in the non-aligned countries of the Global South. It is also important to stress that this report did not analyze Russia and China’s domestic information environments, both of which are critical for understanding continued support for the war, in the case of Russia, or continued support for its ally, in the case of China. As is always the case, the advantage here lies with the autocrats, who can suppress critical information at home while enjoying the advantages of open information environments outside their borders. Despite this imbalance, Ukraine and the West have shown over the past year that information wars can be won, even against those who bend the rules in their favor.

The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the author alone.

- Data was collected by ASD’s Hamilton 2.0 dashboard, which tracks the outputs of Russian state-affiliated media, diplomats, and key government officials. False negatives or positives may occur because of how search terms are processed by the search algorithm, errors with auto-translations, or other variables. In addition, total counts were impacted by a week-long data disruption in March 2022. As a result, queries for specific search terms during this period almost assuredly undercount the total number of uses.